Issue #91 | The History of Sushi | Valuable Lessons from a Lettuce Outbreak | Are Quats Actually Safe? | How Does Salmonella Get into Seafood?

2023-06-05

Welcome to The Rotten Apple, an inside view of food integrity for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for weekly insights, latest news and emerging trends in food safety, food authenticity and sustainable supply chains.

Save the date for our Food Safety for Newbies training on 15th June

Valuable Lessons from a Dole Lettuce Outbreak

Are Quat Sanitisers as Safe as Everyone Thinks?

How Does Salmonella Get Into Seafood?

News and Resources Roundup - includes an emerging Staph pathogen and a 6 year long mystery outbreak

The History of Sushi (funny, good)

Food fraud incidents, updates and emerging issues

🎧 On the go? Listen to me read out today’s email with a free trial subscription - link at the bottom of this email 🎧

It’s Food Safety Week!

Hello and welcome to Issue 91 of The Rotten Apple.

By the way, if you just subscribed, thank you very much 😊. Our subscriber base is growing steadily and it is lovely to have you aboard. Subscriptions help me get through a mountain of food safety and food fraud news for you every week without losing my mind 😵. They cost less than $2.50 per week and are tax-deductible for people who work in the food industry.

This week I’m celebrating international food safety week with

really interesting insights into a lettuce-Listeria outbreak;

a worrying review of the safety of one of the most popular ‘food-safe’ sanitisers;

an exploration of how Salmonella gets in seafood;

heaps of good free webinars in our food safety news roundup.

If food safety systems are new to you, you are going to ❤ love ❤ this month’s free The Rotten Apple training session: Basic introduction to HACCP and food safety systems (for complete newbies) | June 15th UTC 08:00 | Details here

As always, at the end of this issue, you’ll find our ultra-popular food fraud news, for paying subscribers. If you haven’t had a peek behind the paywall, why not take a look with our 7 day trial offer?

Thank you for being part of our food safety community, and have an excellent food safety week.

Karen

P.S. Need more info about paid subscriptions? Click here. Or….

Save the Date! HACCP and Food Safety Systems for Complete Beginners

Save the date for our June training event, which celebrates food safety month by introducing basic concepts of food safety systems, including HACCP and international standards for people new to the industry.

Topic: Basic introduction to HACCP and food safety systems (for complete newbies)

June 15th UTC 08:00 (9:00 am London, 4:00 am New York, 6:00 pm Sydney) | Click here to convert to your timezone |

Everyone is welcome, so spread the word. For more information, and to sign up for pre-event reminder emails, check out our live events page:

🍏🍏🍏 Live Events 🍏🍏🍏

Valuable Lessons from a Dole Lettuce Outbreak

The other day I watched a fabulous presentation by Natalie Dyenson, Vice President, Food Safety and Quality at Dole Food Company who described - with commendable transparency - how she and her colleagues at Dole found the source of Listeria monocytogenes which caused an outbreak from their products in 2021.

There is a link to a replay of the > 1 hour presentation below, but in the interest of saving you time (my main mission!), here are the key learnings.

A mysterious outbreak pattern

The outbreak was traced to salads made in two different states, both containing iceberg lettuce but made with raw materials from completely different growing regions. Genetic sequencing confirmed that (somehow), the exact same strain of L. monocytogenes was present in salads from both states. This genetic similarity means the bacteria almost certainly originated in the same place.

But how did the same strain of Listeria end up in salads from two different factories and two different growing regions? It was a mystery.

Not the usual suspects

A typical pattern for Listeria contamination is for it to occur inside a food processing facility.

Both facilities implicated in the outbreak operated environmental monitoring programs. These programs are a process in which food facility staff take multiple swabs of different parts of the factory on a regular basis, checking for bacteria and other microorganisms.

The main facility in this outbreak had more than fifty thousand data points for Listeria swabs. And only 0.05% of the swabs had detected L. monocytogenes. After the outbreak started thirteen thousand more swabs were collected from both facilities. Dole even dismantled processing equipment so they could swab inside it! The swabs revealed no evidence of Listera contamination in the facilities.

Having ruled out the facilities themselves, the Dole food safety team turned their attention to a common raw material that could have been used in both facilities, such as recycled pallets or corrugated cardboard.

No common raw materials

The team didn’t find any common raw materials between the two facilities. But they did notice that lettuce from two different regions of the United States - and processed in two different facilities - happened to have been harvested by the same crew.

This proved to be the link between the outbreaks traced to the facilities in Georgia and Michigan.

Harvest equipment the culprit?

Lettuce harvest equipment is moved across the country from one growing region to another as the growing seasons change. It turns out that a bulk lettuce harvester used in California was later used in Yuma. And lettuce harvested with that harvester was sent first from California to Georgia and later from Yuma to Michigan. Lettuce from both places was used in the outbreak products.

(BTW How marvellous is this traceability, to be able to trace back to a single harvest crew?!)

Automated harvest equipment hasn’t changed much in the past 100 years. It looks almost the same as it did in the 1920s and 1930s. It was designed to be efficient, relatively lightweight so as not to sink into the soil in fields, and small enough to be moved on inter-state highways. It was designed at a time when most fresh produce was cooked before eating. It was not designed for hygiene.

Mystery solved

The Dole investigation team travelled to a growing area to inspect the harvester implicated in the outbreak. They swabbed various parts of the machinery, including nooks and crannies where leaf debris and dirt were trapped.

They found L. monocytogenes that was an exact genetic match to the outbreak strain.

In the same part of the growing area, a bacterial monitoring database (NCBI WGS) had records of similar strains of L. monocytogenes that had been recovered from just 450 feet away.

The harvester was cut up and sold for scrap.

What did Dole learn?

Dole already knew that once you get bacterial pathogens onto leafy greens they are very difficult to wash off. What they learnt from this outbreak is that unclean harvesters can be a significant source of contamination.

Natalie and her team quickly realised that the design of the conveyor belts and elevators on harvesters make them incredibly difficult to clean. They set about reviewing and improving the hygienic design attributes of harvest equipment.

Dole’s team also reviewed how the equipment should be cleaned, including which chemicals are used, and implemented a process for verifying cleaning and sanitation processes in real time so that cleaners can see how well they have performed their jobs.

Twice a year, the harvest equipment is now subjected to a deep clean, in which the equipment is decommissioned, dismantled, cleaned, assessed, improved and recommissioned.

New equipment is being built with frames that can not hold dirt and bacteria.

Conveyor belts and elevators have been redesigned so that they are easier to clean in place, and easier to remove for deep cleaning.

The outcome?

Dole now considers harvesting “the beginning of the production process”, not the end of the growing process. The equipment used in the harvesting process is as critical to food safety as equipment in the factory and needs to be designed, cleaned and maintained for sanitation.

That is exactly the sort of food safety progress we should be celebrating this week!

Source: CONTACT Webinar, April 6 2023

Next time: How to clean a harvester (in a muddy field, in the dark)

Are Quat Sanitisers as Safe as Everyone Thinks?

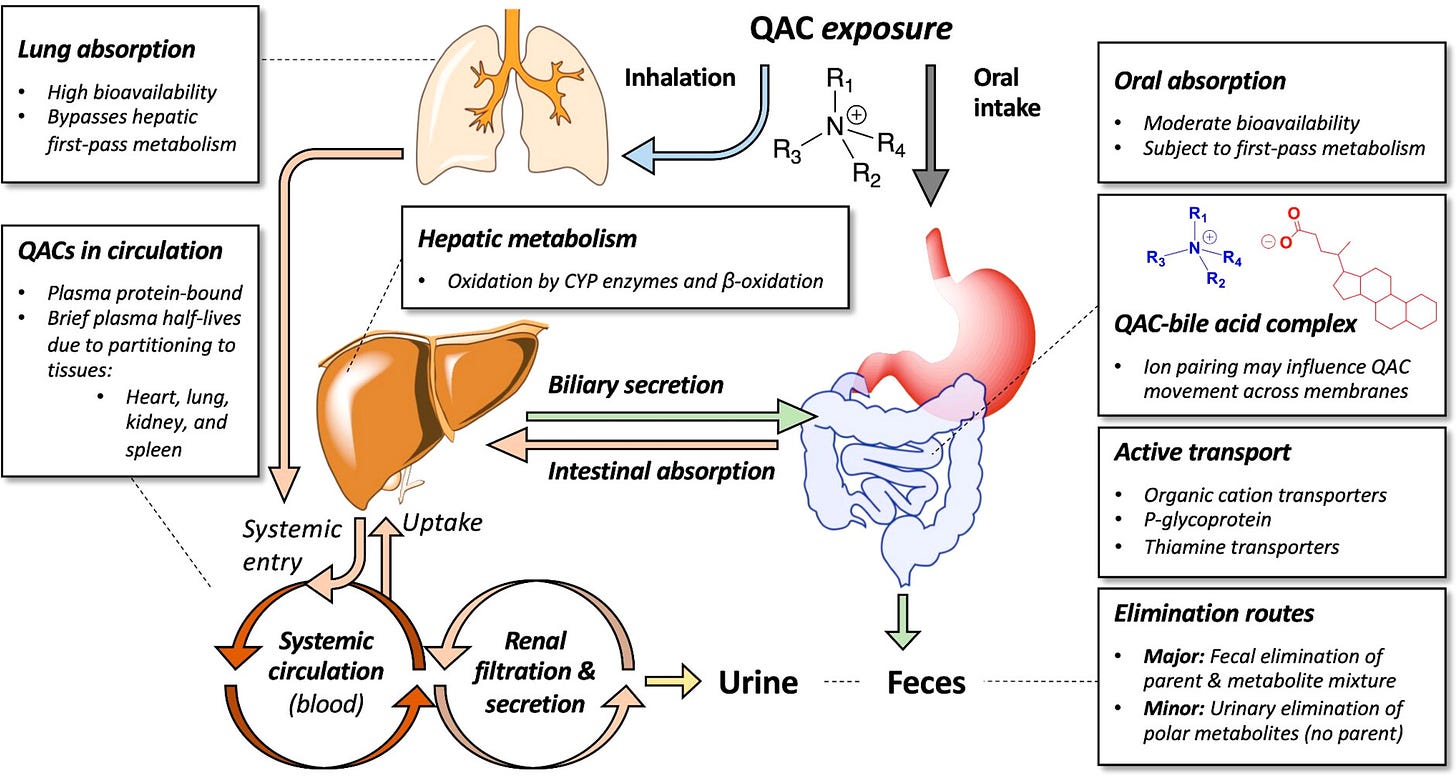

Are one of the most widely used ‘food-safe’ sanitisers harmful? A new review of the safety of quaternary ammonium compound-based sanitisers (QACs) - which are commonly called ‘quats’ in the food industry - really puts the boot in! They are accused of being bio accumulators, environmental toxins and creators of drug-resistant super-bugs!

It’s worrying because the food industry relies on quats as one of the few widely used, widely accepted no-rinse sanitisers for use on food contact surfaces.

Courtney Carignan, a co-author of the review and toxicologist at Michigan State University told The Guardian:

“We did the review to answer the question of ‘What do we really know?’ [about these sanitisers] and what was most surprising was there was a lack of health hazard data in the majority of QACs, and the few that have been studied have red flags”

The health effects reported in the paper are difficult to analyse from a food-industry perspective because QACs are a huge and diverse group of chemicals. For example, a sub-type of QACs often used in food manufacturing is benzalkonium chloride, a QAC with 16 carbon atoms. But there are hundreds, if not thousands of other QACs with carbon chain lengths ranging from 8 to 22. The paper discusses research into the health effects of all the different classes of QACs.

Studies mentioned in the paper have shown that some QACs, including benzalkonium chlorides can accumulate in the body after being ingested or absorbed, which means that if they are harmful, they remain in the body causing harm for measurable periods of time.

Other studies discussed in the paper describe how QACs including benzalkonium chlorides can increase inflammation in humans; changed blood lipid (fat) levels in humans and suppress immunity in rodents.

What does this mean for the food industry?

This paper does not adequately address the risk-benefit profile of quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) when used for cleaning food contact surfaces for achieving food safety outcomes. While further studies might continue to show effects on human health from QACs, these would need to be considered against the risks of not using QACs in food handling processes.

It’s unlikely that anything will change quickly, but we should expect more rigorous investigations into the health risks from QACs and this could lead to changes to rules for QAC sanitisers (far) in the future.

How Does Salmonella Get Into Seafood?

One of my most memorable breakfasts was a delicate dish of precision-sliced raw fish, with a pale, sweet dollop of wasabi on the side, eaten soon after dawn in a sashimi bar in Tokyo’s famous fish markets. The sashimi was so fresh it zinged.

Not many food safety specialists eat raw fish, but if there is anywhere in the world where you can trust your sashimi to be fresh and correctly prepared, it is Tokyo Fish Markets.

Raw fish is risky, and in 2021 it made dozens of people ill with salmonellosis. While we often associate Salmonella with poultry foods, the investigation report for the 2021 outbreak gives us some good insights into Salmonella and seafood.

Altogether, 115 people in the USA were reported as sick, with 20 requiring hospitalisation in the outbreak. The proportion of victims who reported eating seafood and particularly raw fish or sushi was higher than in normal populations, which provided a clue as to which food types might have been the source of the Salmonella.

At the same time investigators were asking victims what they ate, a public health testing laboratory was running genomic sequencing on the Salmonella from the patients.

They discovered that the bacteria from this outbreak was genetically similar to Salmonellae strain(s) that had caused an outbreak in the previous year. In the previous outbreak, sushi-grade tuna and salmon were implicated but investigators could not trace them to a supplier.

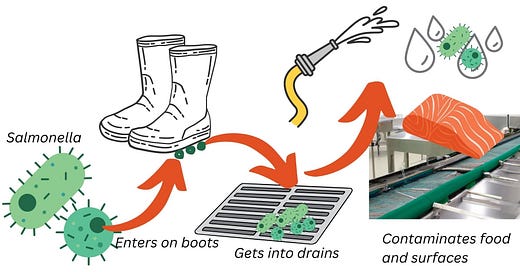

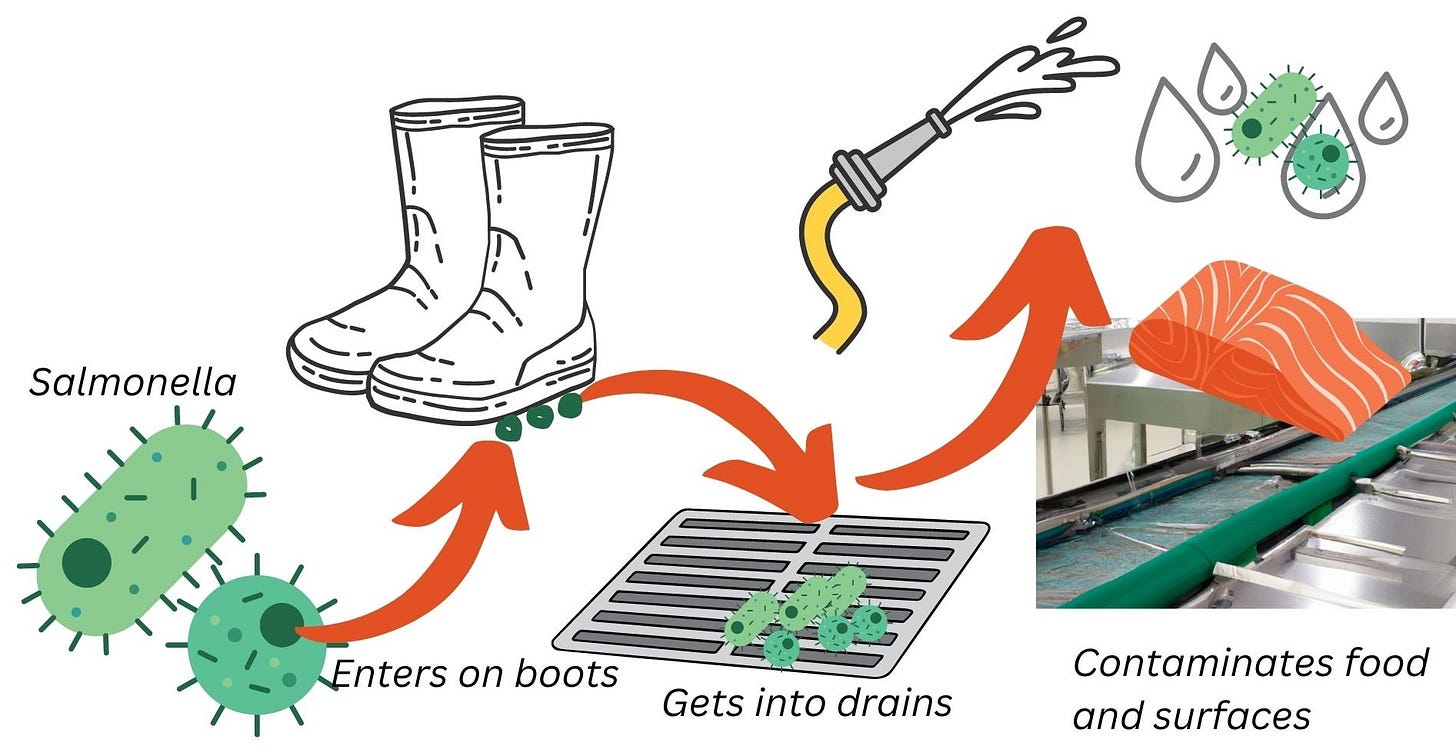

In the later outbreak, the investigators could trace the implicated seafood products to a single seafood distributor. They visited the distributor’s factory and collected swabs from equipment, walls and floors. The outbreak strain was found in 13 of 132 swabs taken from the floor and floor drains.

How did Salmonella get into food from the floors and drains?

Officials from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) who inspected the facility discovered that staff were using high-pressure hoses to clean the floors and drains of the factory while there was fresh product nearby.

This high-pressure washing caused contaminated water droplets to splash onto food contact surfaces like filleting surfaces and cutting boards.

The FDA also noted other hygiene failures at the facility, including incorrect concentrations for sanitisers, condensation dripping onto product contact surfaces and staff cleaning drains with gloved hands, but not changing their gloves afterwards. These are all opportunities for Salmonella to get onto surfaces – and from there onto fish that touches those surfaces.

What was Salmonella doing in the drains and floors in the first place?

Salmonella occurs naturally in the intestinal tracts of humans and animals, including birds, reptiles and farm animals.

Salmonella can get onto floors if a person walks across bird faeces or rodent faeces on the ground. The Salmonella transfers from the person’s boots onto the floor. On a seafood factory floor, which may be constantly wet and littered with food debris, bacteria can grow and multiply. It is possible for a single Salmonella cell to multiply to millions of cells in just a few hours.

In a properly operating factory, floors are thoroughly scrubbed to remove all food debris that could ‘feed’ the bacteria or provide it with shelter from cleaning chemicals. After the debris is removed, floors are sanitised with hot water or chemicals, or both. In this factory, however, the sanitisers were not being used at the right concentration. As a result, live bacteria were probably being washed into drains.

Cleaning drains is difficult. It can be hard to reach every nook and cranny with a scrubbing brush and so biofilms can build up. Biofilms are slimy masses of bacteria which are very difficult to kill with chemicals because they are protected by their own slimy secretions.

Takeaways

For consumers, the main takeaway is that you have to trust that your raw fish is coming from a safe and clean place. The victims of the 2021 outbreak ate sushi that was made with contaminated raw fish. They had no way to tell it was contaminated and that sucks.

I love sushi but I prefer to eat it in a place where I have seen it prepared. Like in Tokyo.

For food safety professionals, the takeaways are non-revolutionary: keep production areas clean; prevent condensation drips from landing on equipment; don’t perform high-pressure cleaning operations when there is exposed food in the area; check sanitiser concentrations every single shift; leave sanitiser in contact with surfaces for the recommended contact time; don’t let biofilms build up in drains; swab; train your staff on correct glove use so they don’t put drain-germs on food 😒.

These hygiene processes are basic but they save lives. And prevent recalls. And save money (A company that had a Salmonella-related recall in 2022 said it cost them around US$33 million).

Could hosing a drain while there is exposed food nearby cause a foodborne illness outbreak and cost your company $33 million? You bet it could!

Main source: CDC Report on the Outbreak

Food Safety News and Resources

This week’s food safety roundup has four free webinars to celebrate food safety week, plus news of emerging prion risks, a new Staph aureus-like food pathogen and a mystery Salmonella outbreak that has been going for 6 years!

Click the preview below to access it.

News and Resources Roundup

5 June | Food Safety News and Free Resources | ✨ 🎈 4 Free Webinars to Celebrate Food Safety Week 🎈 ✨ To celebrate food safety week, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) is hosting 4 free webinars this week: Health consequences of unsafe food: An effort to quantify the burden of unsafe foods

The History of Sushi by Sam O’Nella - Just for Fun

I have not fact-checked this video, which claims to explain the history of sushi, but it’s glorious fun and seems sort of believable. Thanks to my son, Daniel for recommending the channel Sam O’Nella Academy. (Sam O’Nella… get it?!)

What you missed in last week’s email

Audit checklist mastery (how to make a great checklist)

Rewards for whistleblowers

Reusing glass bottles

Crystal-clear gravy (just for fun)

Food fraud news and incidents, including traders who didn’t incinerate a bulk quantity of mouldy almonds, but just sent the shells for incineration instead

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, incident reports, and emerging issues, plus an 🎧 awesome audio version 🎧

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

Massive organic fraud (USA)

An organic farmer who was accused of selling conventionally grown crops as organic in a scheme which prosecutors said generated US$46 million