Issue #99 | 300 Packs of Hallucinogenic Spinach | Good News for Turmeric | Meat Lasers |

2023-07-31

Erratum

Root cause analysis for hallucinogenic spinach, plus the guy who purchased 300 packs of it

A food fraud win for turmeric

News and Resources Roundup

Meat lasers (just for fun)

Food fraud news and incidents

Hello lovely readers,

Welcome to Issue 99. A huge thank you to everyone who has renewed their subscription recently. This newsletter has a 100% retention rate for paying subscribers 😀 woo!

Special mention to Janette Hughes of Melbourne QA who is our latest 🍏 Good Apple 🍏 subscriber. It’s people like Janette who keep this newsletter high-quality and ad-free (and pay our wages!). Janette’s subscription supports scholarships for students and academics. Reach out to me at therottenapple@substack.com to get one. And get in touch with Janette if you need expert food safety services.

So… a crazy guy in a van drove 8,000 kilometres (5,000 miles) to buy 300 packs of spinach contaminated with hallucinogenic weeds last year. I learned this, and much more at last week’s Aussie food science conference. The spinach story is in this issue.

Also this week, a food fraud win plus a correction for last week’s email. And lasers.

As always there’s food fraud news and incidents at the end for paying subscribers, plus an easy-listening 🎧 audio version, so you can give your eyes a rest (and enjoy my accent 😏).

Thank you for being here,

Karen

P.S. “Elegantly curated” and “Highly recommended” were two of the nice things our subscribers said this week (thank you, Milan and Kathryn for jumping aboard). Paid subscribers get access to indexed posts, downloadable past issues and monthly supplements. Click the button to learn more.

Erratum

Last week’s article about non-targeted testing contained an error.

James from a United Kingdom government food organisation, who has used statistical methods for looking at non-targeted data, says PCA, principal components analysis, is not typically used for predictive modelling but is “an unsupervised method that basically looks for patterns in data. It is great for underlying trends in data but as the presentation points out, it is not typically used for predictive modelling.”

Thank you, James, I’m so pleased to have sharp-eyed readers like you to set the record straight when I get things wrong.

How (exactly) Did Toxic Weed Get into Baby Spinach?

Last year, I reported on an unusual food recall, prompted by toxic weeds in baby spinach that caused about 200 Australian consumers to experience hallucinations and delirium.

I was confused by why farm workers and consumers did not notice the foreign leaves before harvesting, packing and eating them.

Happy to say, I found out at last week’s Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology (AIFST) conference! Here’s what I learned.

Attractive symptoms

One man purchased 300 bags of contaminated product after hearing it caused hallucinations.

"The patients that have been quite unwell have been to the point of marked hallucinations where they are seeing things that aren't there. They can't give a good recount of what happened,” said the medical director of the NSW Poisons Information Centre in the Sydney Morning Herald.

The symptoms proved to be so appealing to some people that The Guardian newspaper published a story that urged people not to seek out the contaminated spinach for a recreational high, saying they risked experiencing “really horrible health issues”.

That advice was ignored by a West Australian man. After hearing about the recall he “crowd-sourced” some petrol money to drive across Australia – a return trip of 8,000 km (5,000 miles) and 84 hours - to source packages of the spinach before the recall had been completed.

He managed to procure 300 bags (!) of contaminated spinach and reportedly consumed ‘several’ of them on the drive home, but his haul was discovered during a bio-security check at the Western Australia border.

Strange taste and odour

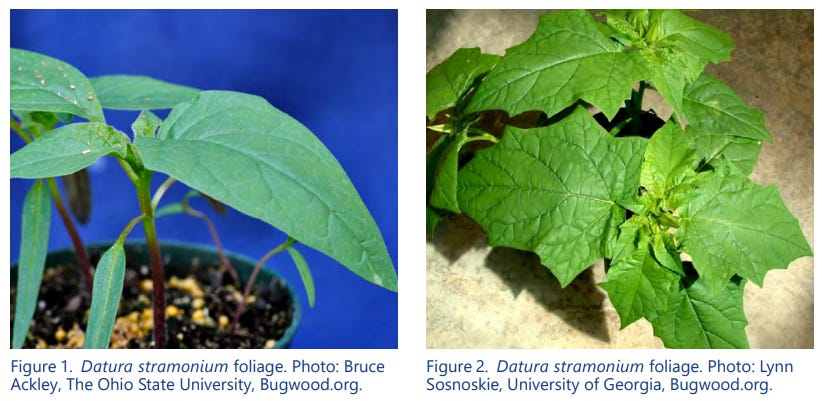

The contaminant that was sickening consumers was identified as leaves of Datura stramonium, known in Australia as thornapple and elsewhere as jimsonweed. I found it strange that consumers, packing-house workers and harvest workers did not notice the thornapple leaves, they usually have an angular shape that is quite different to baby spinach leaves and an unpleasant odour when crushed.

The toxic elements of Datura stramonium leaves are tropane alkaloids, with atropine, hyoscyamine and scopolamine being the main alkaloids present in Datura species. Tropane alkaloids are relatively heat stable and can withstand harvesting, processing and food preparation processes.

Investigation results

The contaminated spinach was used in retail packs, pre-prepared salad packs and salad kits, meals sold by a meals-to-order supplier, and by a national pizza chain.

All affected packs were traced to a single field of a single farm in the South East of Australia. Within that field, the Datura weed was found around one drain or irrigation channel.

Dr SP Singh, who heads the Safe Leafy Veg Program at the NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) shared investigation results with AIFST convention-goers last week.

It is believed that seeds of the weed were introduced to the baby spinach field by either run-off from recent floods, or by intense dust storms of previous dry years.

Germination of the seeds may have been facilitated by deep tillage of the field, which brings old seeds to the top of the soil where they can germinate. Low-density planting, where crop plants are widely spaced can also provide better conditions for weeds to germinate and grow.

Because baby spinach is a fast-growing, short-duration crop (30 to 50 days), herbicides with a long withholding period (time between application and harvest) cannot be used, and there are limited herbicides that can effectively control all types of weeds in baby spinach. This means that the most effective weed control is physically removing weeds from the fields.

Another factor may have been labour shortages which affect farmers’ ability to undertake manual weeding and also impact the experience levels of harvesting crews. Dr Singh mentioned that experienced harvest operators can detect Datura weed by its strong smell.

When the weeds are first emerging they look similar to new baby spinach plants. Both of the images below show Datura stramonium foliage, with the plant on the left appearing more similar to baby spinach leaves than the plant on the right.

Prevention and controls

Because there are limited herbicide options for baby spinach crops, the most important control method for preventing toxic weeds in table spinach and salads is a thorough visual inspection of the field prior to harvest.

The farm at the centre of the recall was accused of poor farming and agricultural practices in a 2018 legal case in which a party to the case claimed that the farm’s carrot and corn fields contained unacceptable levels of weeds and other invasive plants.

Manual weeding can be used to remove weeds, including Datura, from fields prior to harvest, however, it is labour-intensive. Dr Singh shared video showing a modern weeding technology that uses targetted lasers to ‘zap’ weeds from young crops (see below). The laser method is not widely used due to the high cost of the equipment.

Visual inspection during harvest is another control, with workers watching the conveyor belts carrying harvested leaves into the hopper, looking for signs of contamination.

A further control for Datura contamination in spinach fields is the training of workers. The weed has a strong smell when disturbed and experienced workers can detect the weed from its odour.

In short: 🍏 Datura stramonium, the toxic weed that caused illnesses in consumers of baby spinach, was growing in one part of one field 🍏 Juvenile weeds look similar to young baby spinach 🍏 Floods and/or dusts-storms may have introduced the weed’s seeds to the fields 🍏 Deep soil tillage farming techniques and/or low-density planting can allow weed seeds to germinate 🍏 Labour supply challenges reduce weed-control options 🍏Inexperienced workers are less likely to identify contamination with weeds during harvest 🍏

Main sources:

Dr SP Singh, DPI (2023) Were toxic weed (thornapple) leaves on the horizon scan for emerging food safety hazards in leafy salads? (AIFST Convention presentation)

Department of Primary Industries Fact sheet (2023). Managing food safety risks associated with toxic weeds in leafy vegetables. [online] Available at: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/horticulture/vegetables/diseases-pests-disorders/managing-food-safety-risks-associated-with-toxic-weeds-in-leafy-vegetables.

Laser weeding demonstration, by Carbon Robotics on YouTube

A Food Fraud Win for Everyone’s Favourite Yellow Spice

Turmeric, like all spices, is vulnerable to food fraud. Its vulnerabilities are related to its value (expensive), its supply chains (complicated, with many small farmers and traders) and its physical properties (colour, aroma, powdered forms).

Turmeric was found to be ‘suspicious’ with respect to adulteration, at levels of 11% in a Europe-wide survey of 1885 samples of herbs and spices in 2021. A common form of food fraud adulteration for spices is the addition of undeclared and unapproved colourants such as textile dyes or unauthorised food additives. The colours increase the apparent value of the spices by making them look fresher and more appealing.

Colourants used to adulterate turmeric include lead chromate, metanil yellow, acid orange 7, Sudan Red G , Sudan I and Tartrazine, with lead chromate being the most concerning.

In 2016, routine sampling by New York State (USA) food inspectors found high levels of lead in retail turmeric, leading to a recall of multiple brands in the USA. Authorities in India were reporting the same thing in 2016. The following year, researchers in Boston (USA) found fifty percent of the turmeric they purchased from retail outlets (32 samples) contained high levels of lead.

In 2019, researchers reported that seven of nine turmeric growing areas in Bangladesh showed evidence of turmeric adulteration with lead chromate. Levels of lead exceeded limits by up to 500 times (source).

Tackling the problem in Bangladesh

The same researchers who found lead chromate usage in Bangladesh in 2019 have just published a paper that describes how they partnered with local authorities to make positive changes for the turmeric supply chain in that country (brilliant!)

Mohammad Abdullah Sheikh is a Bangladeshi turmeric trader who added lead chromate to his wares during the polishing process for whole turmeric roots.

The polishing process removes the outer layer of the root to reveal the yellow-gold-coloured interior. Lead chromate, a brightly-coloured textile dye, gives the roots an intense yellow colour which is associated with high-quality, fresh roots.

Mohammad learned this colour-boosting trick from other turmeric traders, who started doing it after a large flood affected the Bangladesh turmeric crop in 1988. He found he could sell his turmeric for higher prices when it had been polished with lead chromate.

Mohammad does not use the dangerous colourant any more and is sorry for his past actions. “I have to answer to Allah that I used [lead-chromate] in food,” he says.

“I have to answer to Allah that I used [lead chromate] in food” - Turmeric trader who stopped using the dangerous colourant after a successful intervention campaign in Bangladesh

The change came about after the researchers partnered with the Bangladesh Food Safety Authority to develop a national intervention program to reduce turmeric adulteration with lead chromate.

The intervention educated traders like Mohammad on the harmful health effects of the yellow dye. Many of the traders had been feeding the adulterated spice to their own children, unaware of the health effects 😥

Intervention methods included (a) using news media to make people in Bangladesh aware that turmeric was a source of lead poisoning (b) educating business owners and consumers about the risks of lead chromate in turmeric using public notices and meetings (c ) using rapid detection methods to enforce policies which already outlawed the adulteration of turmeric.

Positive results

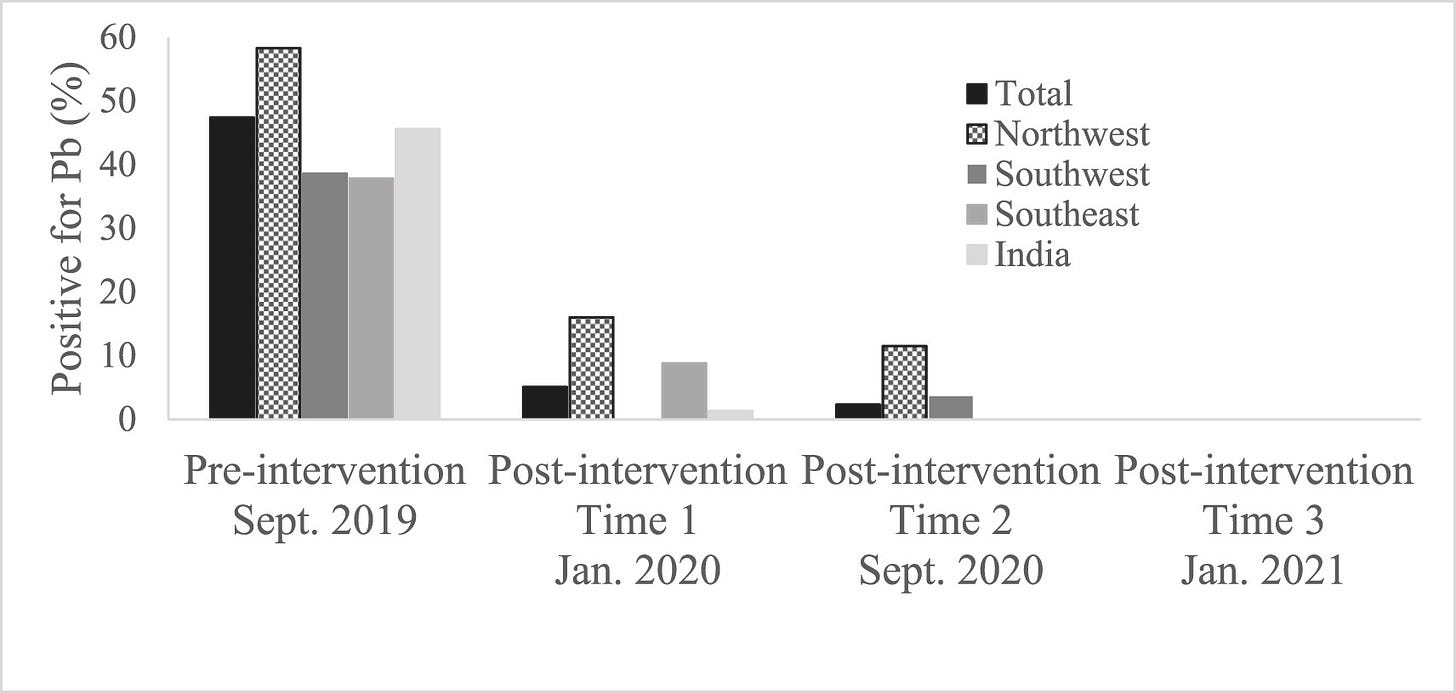

It’s fair to say the intervention worked very well, reducing the usage of lead chromate in turmeric polishing mills to zero and the proportion of contaminated products from almost half to none.

The incidence of lead adulteration in turmeric purchased from a major Bangladesh wholesale market fell from 47% of samples to 0%.

The percentage of turmeric processing mills adding lead chromate to turmeric decreased from 30% to 0%.

Workers in the turmeric mills experienced lead blood levels drops of 30%.

Percentage of turmeric samples with detectable lead levels (n = 631) purchased from a major wholesale turmeric market in Bangladesh before, during and after the intervention. Source: Forsyth, et al (2023). Food safety policy enforcement and associated actions reduce lead chromate adulteration in turmeric across Bangladesh. Environmental Research. In short: 🍏 Lead chromate adulteration of turmeric is a type of economically motivated adulteration (food fraud) 🍏 The fraud is perpetrated to make the spice more strongly coloured, which increases its apparent value and price 🍏 Researchers who found high levels of lead in Bangladeshi turmeric, turmeric mills and mill-workers’ blood worked with local officials to reduce the problem 🍏 The intervention included education and enforcement 🍏 Results were excellent, with lead usage dropping to zero in mills in the intervention areas 🍏

Main sources:

Forsyth, J.E., Baker, M., Nurunnahar, S., Islam, S., Islam, M.S., Islam, T., Plambeck, E., Winch, P.J., Mistree, D., Luby, S.P. and Rahman, M. (2023). Food safety policy enforcement and associated actions reduce lead chromate adulteration in turmeric across Bangladesh. Environmental Research, [online] 232, p.116328. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.116328.

The Vice of Spice: Confronting Lead-Tainted Turmeric (2023), undark.org

Food Safety News and Resources

Our news and resources section includes not-boring food safety news plus links to free training sessions, webinars and guidance documents: no ads, no sponsored content, only resources that I believe will be genuinely helpful for you.

Click the preview box below to access it.

News and Resources Roundup

31st July | Food Safety News and Free Resources | 💀⚠ 3 dead from Listeria in unknown food (USA), and 3 dead with listeriosis possibly linked to smoked salmon (Sweden)⚠💀 Five people have been hospitalised and three have died from listeriosis in Washington State. The food source has not been identified.

Meat Lasers (Just for Fun)

This 17-minute video from the “only bioengineer on YouTube crazy enough to try [making a meat laser]” explains how to make ordinary dye lasers from rhodamine dyes and the theory of making dye lasers from proteins. The proteins can be made by genetically modified E. coli. Or, theoretically, in cultivated meat cells.

Why make a laser out of meat?

Because, “let’s be honest, those cyclops powers aren’t going to make themselves”.

What you missed in last week’s email

The weird link between non-targeted food testing and protecting the Amazon rainforest

Is training needed - the ultimate decision tool (for paying subscribers)

Blazing trails: the SOP that’s setting the supplement industry on fire

Watermelon tastiness measurement (just for fun)

Food fraud news, incidents and updates

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news and incident reports, plus an 🎧 audio version of this issue 🎧

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

Honey origin fraud on a huge scale

Government investigations revealed large-scale country-of-origin fraud in honey in