122 | Microplastics in Food | Introduction to Hygienic Design | Silly Food Claims |

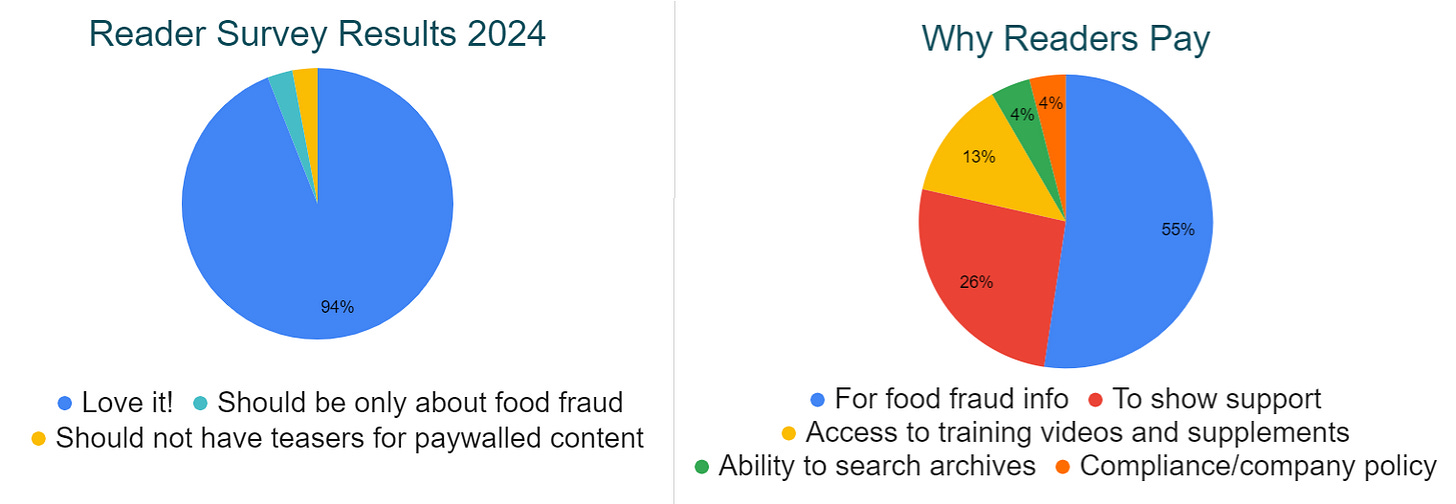

Plus, a downloadable checklist and reader survey results

Introduction to hygienic design principles (plus downloadable sanitary design checklist);

Microplastics: do we really eat a credit card’s worth of plastic each week?

Reader survey results (with colourful pie charts!);

Food Safety News and Resources;

Silly food claims;

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents

Oops! All my excitement about lobster rolls fell flat last week when the link broke. Here’s the corrected story.

Welcome to Issue 122, thanks for joining me.

In this week’s issue, I delve into the nitty-gritty of hygienic design principles and share my best-ever sanitary design checklist in downloadable format for paying subscribers.

Also, do we really eat a credit card’s worth of microplastics in our food each week? The latest research raises more questions than answers. Plus, I’ve got a bunch of free webinars for you in this week’s food safety news roundup.

Warning: This week’s Just for Fun section has silly food claims that will make food scientists cringe.

Have a great week.

Karen

P.S. Shout outs to 👏👏 Chase for upgrading to paid subscriptions, and to Karina 👏👏 for your ongoing support. This newsletter would not exist without the financial support of readers like you, thank you.

Reader Survey Results

Thank you so much for responding to the reader survey emails. Here are the biggest takeaways:

A significant portion of paying subscribers are paying to show support for my work (thank you!);

Ninety-four percent (94%) of respondents love the newsletter’s current focus and format 😊

Packaging and food fraud in packaging were requested in a few responses. Noted!

Hygienic Design Principles

When equipment and facilities are not easy to clean, food safety failures are almost inevitable. Failures in hygienic design can lead to food contamination and cause deadly outbreaks.

Learn how to select food equipment, fixtures and facilities by following the principles of hygienic design, and get an exclusive sanitary design checklist that is both comprehensive and simple to use in this month’s supplement for paying subscribers.

Introduction to Hygienic Design (Plus the only sanitary design checklist you will ever need)

Hygienic design is a set of principles for designing food equipment and food handling areas that are easy to clean and that stay clean for longer. It is also referred to as sanitary design. Hygienic design aims to protect food from contamination. Hygienic design is fundamental to food safety. It involves creating environments and equipment that are inherently less likely to harbour or transmit contaminants, thereby reducing the risk of food contamination and food-borne illness.

Microplastics in Food

… Are we really eating one credit card per week?

In 2019 Australian researchers published a paper claiming we each unintentionally consume around 5 grams of plastic each week. That’s the same as eating a credit card. How? By eating foods that contain microplastics.

Wow.

The research has since been unpacked and disputed, more on that later. First, what are microplastics exactly?

What are microplastics?

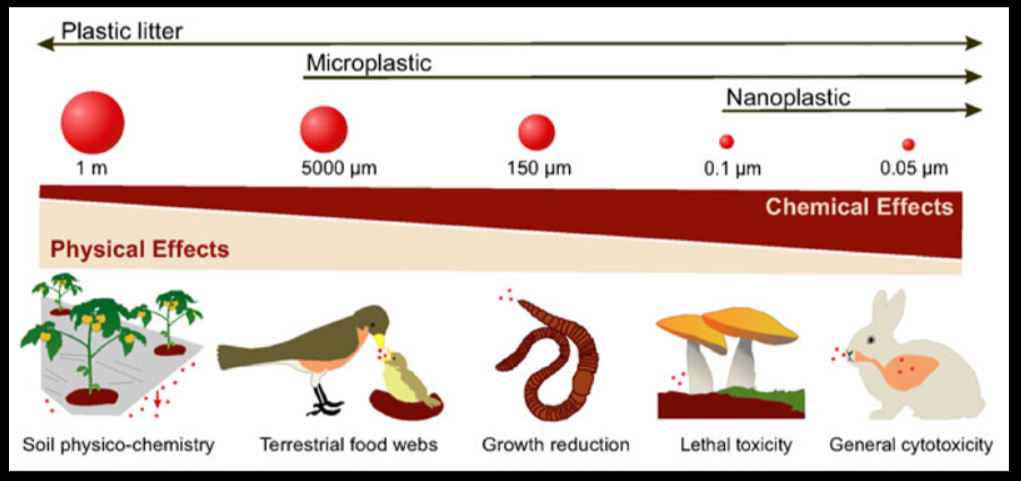

Microplastics are pieces of plastic that are smaller than 5 mm (3/16 inches).

Microplastics form when objects made from plastic are damaged or degraded. Or they are formed that way deliberately, as with the tiny abrasive beads which were used in washing powders, facial cleansers and toothpaste until being phased out in most countries.

How do plastics turn into microplastics?

Plastic items like food packaging, clothing made from synthetic fibres and building materials can break down and degrade into microplastics through mechanical means - for example, one fleece jacket can shed 250,000 plastic fibres during one wash cycle - and by chemical degradation such as by breaking down in sunlight. Some microorganisms can also contribute to the degradation of plastics.

How do microplastics get into food?

Microplastics end up in human food through various pathways. They can be taken into the bodies of the plants and animals we eat, they are present in the water we drink, and they can contaminate our foods during processing and from the foods’ packaging during transport and storage.

I recently attended a fascinating talk (Reichman, 2023) where the presenter shared some interesting new knowledge about microplastics in food.

For example, she explained that a microplastic particle commonly found in milk is a blue fibre made of polyethersulfone and/or polysulfone. This blue material is used for filters in milk processing operations.

Other unexpected pathways for microplastic contamination of food include butchers chopping meat on plastic boards, fibres or fragments of plastics from tea bags, polystyrene particles from meat trays and takeaway containers, and particles from bottled water containers and lids.

Are biodegradable and recycled plastics extra risky?

There are almost no studies on microplastic generation from biodegradable plastics or recycled plastics, said Reichman. However, we do know that some ‘biodegradable’ plastics were deliberately designed to break down into microplastics quickly, so some microplastics are the direct result of ‘biodegradable’ plastics.

Experts also suspect that the processes used for recycling plastics are capable of concentrating contaminants such as heavy metals in the recycled products, however, that has not yet been investigated.

Do we really put microplastics in soil on purpose?

Microplastics have been extensively studied in oceans, but few studies address their presence on land. In soil, microplastics can be present by accident. For example, from the breakdown of irrigation hoses, or deposition from the atmosphere.

Microplastics are also deliberately added to soils through the use of plastic mulches for water conservation and plastic coatings which are applied to fertilisers and seeds. The coatings are used to provide slow-release characteristics for fertilisers and to extend the life of seeds.

How much is present in food?

Microplastics have been found in every food that has been surveyed, says Reichman.

The concentration of microplastics in foods is hugely variable across different food types and within the same foods. For example, there are large variations between the amount of microplastic in different parts of the same fish. Fillets (muscle) tend to have fewer microplastics, while whole fish have more. Filter feeders such as shellfish contain more microplastics than other types of seafood (Dawson, et al. 2021).

In samples of table salt, the variation is notable. Researchers have found less than 1 particle per kilogram in some samples and 2,500 particles per kilogram in others. The type of plastic is also highly variable. In salt researchers found polypropylene, polyethene, polyvinyl chloride and others (Vitali et al, 2023).

Do microplastics harm us?

Because microplastics are incredibly diverse in their shapes and materials of composition, it is impossible to generalise about their effects on us. For example, polyvinyl chloride is relatively more ‘toxic’ than polypropylene; some plastic materials contain additives such as BPA and phthalates, while others do not; and some microplastic particles have larger surface areas or ‘sharper’ shapes rendering them potentially more harmful than others.

We can inhale microplastics from carpets, clothes and furniture upholstery, but the main sources of human exposure are food and water. Li et. al (2023) suggest microplastics cause inflammatory responses, interfere with our immune system, cause oxidative stress injury, and affect the gastrointestinal tract.

There is a range of possible modes of action when it comes to harm from microplastics, including physical damage to our internal structures from larger particles and fibres, as well as the toxicity of the plastics themselves or toxic effects from other environmental chemicals which are sorbed onto microplastics and released into our bodies when the particles are ingested.

Challenges with measurements

Measuring microplastics in food, water and the environment is a difficult task. It’s physically challenging to separate plastic particles from carbon-based materials like food and blood without damaging them.

Smaller particles are thought to be more toxic than larger particles but measuring smaller particles is more technically difficult, and the methods are more labour-intensive compared to measuring larger particles. For smaller particles, analytical methods such as TED-GC-MS are used, which can cost more than one thousand dollars per sample. This makes surveys and monitoring prohibitively expensive.

A further challenge is that many animal toxicity studies have been done with spherical-shaped microplastics which are newly manufactured. These, however, are not representative of microplastics found in natural environments, which are more commonly fibre-shaped, and composed of weathered (older) polymers. This means the animal toxicity tests could be significantly underestimating the risk of harm.

So how much are we (really) eating?

When researchers reviewed the human intake literature in 2023, they found just four previous studies had attempted to estimate how much microplastic is in our diets.

The researchers who suggested 5 grams per week used just four food types to estimate intake: drinking water, shellfish, salt and beer. They also noted the extreme challenges with both measurement of particles in foods and extrapolation to populations.

A review of those estimates suggested they were probably too high but noted that we only have data for very few food types, and that the reliability of the data is “questionable” because there is no validated method available.

The ultimate conclusion: we just don’t yet have enough data to properly assess the human intake of microplastics and therefore can’t make an estimation of the food safety risk (Pletz (2023).

Sources:

Main source: Let’s Talk About Microplastics in Food, Presentation by Prof Suzie Reichman, University of Melbourne (2023), Hosted by the Australian Insitute of Food Science and Technology (AIFST)

Dawson, A.L., Santana, M.F.M., Miller, M.E. and Kroon, F.J. (2021). Relevance and reliability of evidence for microplastic contamination in seafood: A critical review using Australian consumption patterns as a case study. Environmental Pollution, 276, p.116684. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116684.

de Souza Machado AA, Kloas W, Zarfl C, Hempel S, Rillig MC. Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems. Glob Chang Biol. 2018 Apr;24(4):1405-1416. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14020. Epub 2018 Jan 31. PMID: 29245177; PMCID: PMC5834940.

Li, Z., Yang, Y., Chen, X., He, Y., Bolan, N., Rinklebe, J., Lam, S.S., Peng, W. and Sonne, C. (2023). A discussion of microplastics in soil and risks for ecosystems and food chains. Chemosphere, 313, p.137637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137637.

Pletz, M. (2023). Ingested microplastics: Do humans eat one credit card per week? Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters, 3, p.100071. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazl.2022.100071.

Senathirajah, K., Attwood, S., Bhagwat, G., Carbery, M., Wilson, S. and Palanisami, T. (2021). Estimation of the mass of microplastics ingested – A pivotal first step towards human health risk assessment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 404, p.124004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124004.

Vitali, C., Peters, R., Janssen, H.-G. and W.F.Nielen, M. (2022). Microplastics and nanoplastics in food, water, and beverages; part I. Occurrence. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, p.116670. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2022.116670.

Food Safety News and Resources

This week’s food safety roundup has heaps of free webinars. And a very odd recall.

Click the preview box below to access it.

Food Safety News and Resources | January

22 January | Food Safety News and Free Resources | Large outbreak from drinking water (China) | Cinnamon-apple puree + lead chromate update (USA) | Boron and off-flavours in carbonated water (Germany) | World first: Cultivated beef approved for sale (Israel) |

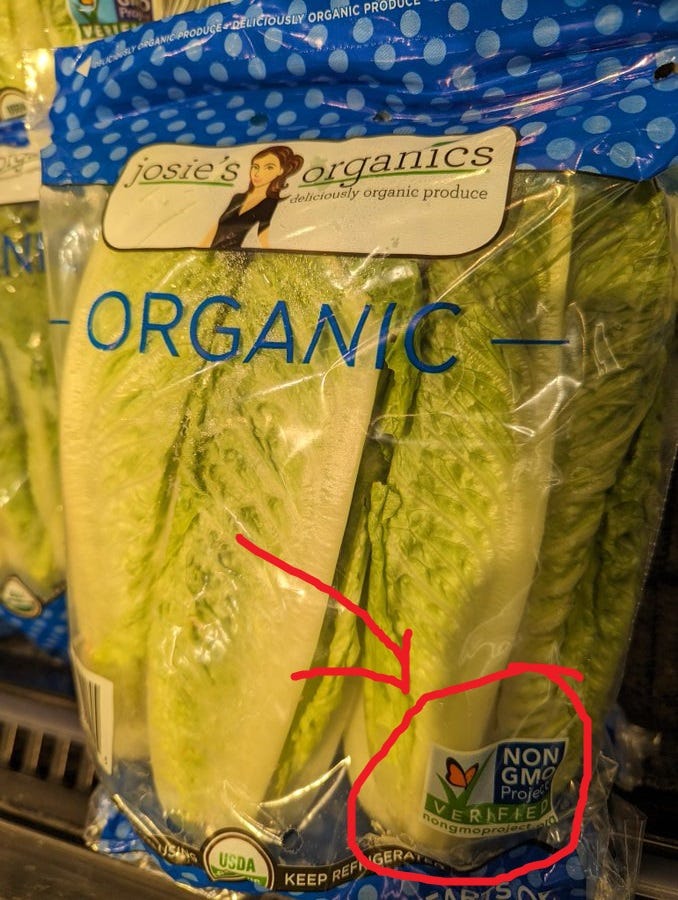

Weird Food Labelling (Just for Fun)

Found these two doozies on the interwebs this week: carbon-free sugar and non-GMO lettuce. Righto.

What you missed in last week’s email

When food fraud goes (horribly) wrong;

Allergen cross-reactivity;

Food Safety News and Resources - lots of guidance and webinars this week;

“We’re making lobster rolls!” (just for fun);

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents, including an expected recommendation about sniffing food supplements

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, horizon scanning and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

Win the fight against food crime (Event)

Campden BRI in the UK is holding an in-person event to share the latest information about identifying and dealing with food fraud. It is