148 | Food Fraud 2024 | Bird Flu in Milk | Cyclospora |

The latest in food safety from the IAFP conference

This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

Food fraud 2024 - what the experts say;

Cyclospora, a growing food safety threat (or not?);

Highly pathogenic avian influenza in dairy foods;

Food Safety News and Resources;

Did you know… (facts and quotes from IAFP);

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents

Hi,

Welcome to Issue 148 which is dedicated to insights from the food safety extravaganza that was IAFP 2024. Held in California last week, it had 3,300 attendees making it by far the biggest professional event I’ve attended. To my surprise and delight it didn’t just have great content, it also had ‘a good vibe’, with positive energy and lots of friendly smiling faces.

I’ve returned from my US travels with a new-found appreciation for Australian food, a minor case of jet lag and (bonus!) a parasitic intestinal worm infection. Guess I was right to be nervous about eating so many raw leafy greens in the US.

I also had the opportunity to meet many of my wonderful readers in person. Shoutout to Julie, Elise, Jashan, Oyalinka, Stephen, John, Allison, Claire, Mark and everyone else, I loved meeting you all.

In today’s issue, I share insights about new hazards in dairy foods from the bird-flu-in-cows drama which is unfolding in the US. This is the most up-to-the-minute information, sourced straight from experts at the CDC, FDA, USDA, Cornell University and industry, presented last Tuesday at the IAFP event.

Also this week, new learnings in food fraud, insights into Cyclospora and a few of my favourite quotes from the event.

Enjoy,

Karen

P.S. Thank you to new paying subscribers 👏👏 Kate, ‘Procurement’, Elizabeth, Sera and Fiona 👏👏 for supporting everything I do to grow our community of global food safety champions.

Food Fraud 2024

Insights from the IAFP roundtable on food fraud can be found in a special supplementary post for paying subscribers. Click the preview box below to view it.

Food Fraud Roundtable 2024 - What the Experts Said

Table of Contents About the roundtable Certification body expectations for food fraud prevention Regulatory expectations for food businesses The role of analytical testing in food fraud prevention Common mistakes in vulnerability assessments Analytical testing considerations

Cyclospora – a growing food safety threat (or not?)

The information presented here is mostly sourced from a presentation by Michelle Danyluk, University of Florida, from a session titled Root Cause Analysis for Non-cultivable Foodborne Pathogens at IAFP 2024.

Cyclospora infection is a foodborne and waterborne illness caused by Cyclospora cayetanensis, a single-celled parasite (technically, a coccidian protozoan). In wealthy countries, it was rare until recently, and only seen in people who had travelled to tropical developing countries, where the parasite is endemic.

However, since the 1990s, Cyclospora infections are now seen commonly in wealthy countries as well as developing countries.

Cyclospora infections take around one week to develop and cause symptoms, and the illness can last from a few days to more than a month. Symptoms include watery diarrhoea, bloating, flatulence, burping, abdominal pain, cramps, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, body aches, fatigue, and fever.

The most common food sources for Cyclospora infections are fresh produce such as leafy greens, salad mixes and fresh basil. In the United States, Cyclospora outbreaks were only linked to imported produce prior to 2018. However, after 2018 there started to be many cases of Cyclospora in people who had not travelled internationally, and at least some of these cases were presumed to be from domestically grown food.

I say ‘presumed’ because Cyclospora cannot be cultured in the laboratory and is not suitable for genetic sub-typing, making it very difficult to link food samples and environmental samples with infected people.

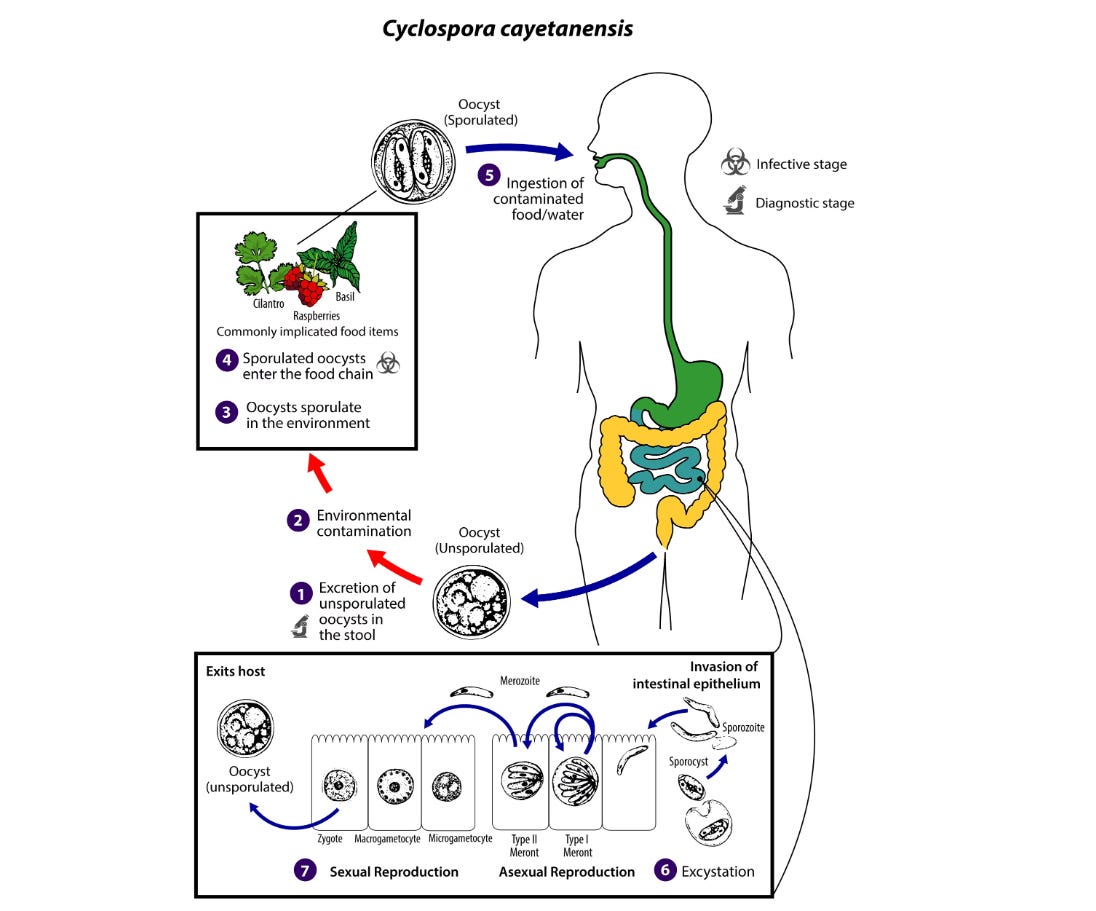

How does Cyclospora cause foodborne illness?

Cyclospora is transmitted when infected human faeces contaminate food or water. It is not transmitted directly from person to person because it is not infectious until one to two weeks after being passed in a bowel movement. The infectious agent is the oocyst of the parasite (a sort of ‘egg’), which is excreted in the faeces of an infected person. The parasite forms the oocysts while living inside its human host.

After leaving its host’s body, the oocyst sporulates (‘hatches’). The sporulated oocysts cause illness when ingested in food, such as raw leafy greens, or perhaps in contaminated water.

Little is known about the biochemistry of Cyclospora oocysts, or their sporulation process. It’s not even known whether they sporulate while on food crops or elsewhere, such as in soil or water. Nor is it known how many oocysts survive in the environment, how long they survive on crops, whether they are killed by solar radiation, or how easy it is for them to cross-contaminate from soil or water onto food. It’s also not known whether they can be physically removed from food plants such as leafy greens.

Fortunately, thorough cooking does inactivate Cyclospora oocysts.

It is thought that Cyclospora oocysts get onto food plants such as leafy greens through direct contact with contaminated hands – such as from farm workers – or from contact between contaminated irrigation water and crops. However, the transmission process from irrigation water to crops is unknown.

Irrigation water cannot easily be monitored for the presence of Cyclospora oocysts because they are very difficult to detect in water, and the methods used for recovering oocysts from environmental samples is often questioned, with a lack of consensus in the science community around the methodology.

Agricultural water treatment chemicals in common use have limited efficacy against Cyclospora.

How big is Cyclospora as a food safety problem?

We don’t have a lot of data about how many people have Cyclospora, or how many oocysts people shed when infected. We also don’t know what the infectious dose is for Cyclospora.

This makes it difficult to understand how much of a risk it poses within food supply chains. However, case numbers in the United States appear to be on the rise with some scientists now considering it endemic in the US. Other scientists suggest that the increased effectiveness of clinical tests may be the reason for the sudden apparent increase in domestically acquired cases in wealthy countries.

Controls for Cyclospora

Some experts suggest we could solve the problem of Cyclospora by eliminating it entirely from the population, while others say we should prevent its spread using food safety controls. Unfortunately, once the oocysts get onto food, it is difficult to know whether they are present, due to a lack of easy detection methods, and as mentioned previously, there are no known ways for removing them from food that is intended to be eaten raw.

Because it cannot grow or replicate outside the human body, prevention of Cyclospora must focus on keeping human faeces away from food and water. As Dr. Danyluk said of finding the source of contamination in Cyclospora outbreaks, the key is to…

Focus on the poop.

💩💩💩

Source: Presentation by Michelle Danyluk, University of Florida, from a session titled Root Cause Analysis for Non-cultivable Foodborne Pathogens at IAFP 2024.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) in dairy foods

I attended a last-minute expert panel on highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus at last week’s IAFP food safety conference in the US. Here’s what I learned. Sources and further information can be found at the end of this post.

The panellists made it clear that the discovery of the virus in dairy herds and dairy food in the US earlier this year took everyone by surprise. They said they had initially expected the situation to be resolved quickly because only a few cows were affected and the industry thought it would “burn out” during the summer months.

Months later, the number of infected herds continues to increase. We are now looking at a long timeframe before this situation will be resolved, with panellists talking in terms of “months, if not years”.

“This was a surprising situation for everyone involved” (Jennifer Sinatra, USDA)

“We thought we would get through this a lot sooner than we are” (Clay Detlefsen, National Milk Producers’ Association)

Background: Bird flu (highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1)) was discovered in dairy cows in the USA earlier this year. It was later discovered in raw milk. Genetic material from inactive viral particles was found in a significant number of pasteurised milk samples from retail stores.

There have been concerns that the virus could be transmitted to people who consume dairy foods from infected cows. We’ve been reporting on this issue in our weekly (free) Food Safety News Roundsups.

Food safety risks from highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) in the dairy industry

What we know

Milk from infected cows contains the virus, and such milk may have the ability to cause illness in consumers, based on the results of testing with mice.

Pasteurised milk purchased from retail outlets in the USA has been found to contain genetic material from the virus, however, the virus was not infective in any samples.

Pasteurisation does inactivate the virus, with the FDA saying they are confident that commercial pasteurisation is “very effective” at inactivating H5N1 (5). Early information about the efficacy of pasteurisation was based on tests conducted with bench-top pasteurisers, which do not accurately mimic commercial processes, and this led to initial concerns about the safety of pasteurised milk (3). The FDA, USDA and their partner research laboratories are now categorically stating that pasteurised milk is absolutely safe.

Cheese and other dairy foods made from pasteurised milk are also safe.

Raw (unpasteurised) milk poses serious risks to consumers from the potential presence of the ‘live’ virus in such milk.

🗨 On the topic of raw milk, I was gobsmacked to learn that raw milk consumption in the US has increased sharply since the public learned about this situation. Yes, you read that correctly, raw milk consumption has “spiked” in recent months in the United States (source: panel members). More on this later 🗨

What we don’t know

We do not have enough information yet about how or if the virus survives in cheeses and other dairy foods made from unpasteurised milk. Among the panellists, the consensus seemed to be that the virus will eventually deactivate in aged raw milk cheeses, but the question is ‘how fast’?

The survival of the virus in dairy foods made from unpasteurised but sub-pasteursation-thermally-treated milk is likewise unknown.

The Z and D values, thermal inactivation kinetics and inactivation curves for the virus in dairy foods have not been determined yet.

The fat content of milk makes a big difference to how the virus is inactivated. Low fat allows for faster/easier inactivation compared to high fat(3).

The safety of milk and dairy foods made with high-pressure pasteurisation (HPP) and ultra heat treatment (UHT) was not discussed in the session.

Why don’t we know more?

There are extreme challenges with understanding how the virus ‘behaves’ within foods. Firstly, there are strict biocontainment rules that mean you need a special laboratory if you want to study the virus. In fact, until recently, when this virus was reclassified, it used to cost ten thousand dollars to ship one vial of sample across the country (3).

Secondly, it’s difficult to ‘grow’ enough virus to make spiked samples for testing. Ideally, naturally contaminated milk is better for testing, but it is challenging to obtain enough naturally contaminated milk.

Thirdly, figuring out whether viral particles are ‘alive’ (infective) or ‘dead’ in heat-treated foods is not simple and includes the need for highly specialized tests in which viral particles are inoculated into eggs to see if they are infective.

Fourthly, it is extremely difficult to simulate high-volume food processing systems such as continuous pasteurisation in a bio-containment laboratory. A $100,000 piece of equipment was custom-built for the recent pasteurisation studies which were conducted in the USDA lab which had been studying the virus in poultry.

“Trying to [take a] sample from the middle of a pasteuriser when it’s under pressure is very difficult.” David Suarez, USDA

How did this happen?

It seems that the virus, which usually infects birds, infected one or more dairy cows and was then spread to cows on other farms through the movement of vehicles, equipment and people. Animal health studies indicate milking equipment could be a key route of viral transmission.

Can people catch bird flu from infected cows?

Yes, people who work closely with cows are at risk and there have been some cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) in farm workers in the USA in recent months. There is minimal risk to people who do not work with cows.

Are other food-producing animals also at risk?

There is already a lot of science around the risk to pigs from bird flu. Pigs appear relatively resistant to infection – they can catch it but they are not particularly vulnerable(3). There is already a strong influenza surveillance program for swine in the US that is likely to find it if it infects a pig herd.

It is not known whether the poultry industry faces risks from infected dairy cows.

What about dairy herds in other countries?

I asked the panellist from the National Milk Producers’ Association about what his counterparts in other countries are doing about this, but he did not know. I am not aware of any infections in dairy animals outside the United States.

Is the virus evolving?

There is a lot of surveillance, and the virus is sequenced for every outbreak and every farm. It has also been the subject of surveillance in the poultry industry for years. There is not a lot of evidence that the virus is becoming more dangerous to mammals (3). Within humans, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is performing routine surveillance for influenza, including for ‘novel’ influenzas such as H5N1.

What about raw milk consumers?

During the session, there was a lot of talk from the panellists about how well the various government agencies such as FDA, USDA and CDC were cooperating with each other, and with academia and industry.

However, when the discussion turned to risk communications for raw milk, the panel had less to say.

Two panellists said that consumption of raw milk seems to have increased in recent months (2, 6). One theory to explain this is that “people are freaking out” about commercial milk and are concurrently being told on social media platforms such as TikTok that raw milk is safer, making it seem a better choice.

“Raw milk consumption appears to be spiking” (Clay Detlefsen, National Milk Producers Association)

Bizarrely, although the FDA “reiterates its long-standing recommendation not to consume raw milk” it appears, at least to the knowledge of the FDA representative on the panel(5), that there are no new recommendations for consumers based on the current situation, nor do there appear to be any messages being actively distributed to consumers about the dangers presented by raw milk.

Representatives of both the CDC(1) and the FDA(5) said they have information about raw milk on their websites but do not have social media or traditional media campaigns about the new dangers from this virus in raw milk.

In addition, panellists mentioned that safety messages from their agencies might be counterproductive because consumers have lost trust in the government.

Takeaways for food professionals

For the dairy industry internationally the big takeaway is that biosecurity measures should be reviewed, and the movement of equipment, vehicles and people between dairy herds should be controlled. Note that new biosecurity protocols are voluntary in the US, and based on govt recommendations, there are no new federal regulations to address biosecurity risks from these outbreaks.

Pasteurisation inactivates highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1), rendering pasteurised milk and dairy products made from pasteurised milk safe for consumers.

Raw milk has the potential to cause avian influenza infections in consumers. Raw milk cheeses, ice creams and other dairy foods may also be risky. We don’t know much about the safety of raw milk cheeses and have no thermal inactivation curves for the virus at this time.

Takeaways for consumers

Don’t drink unpasteurised (‘raw’) milk or eat dairy foods made from unpasteurised milk in the United States.

🍏🍏🍏

Panellists: (1) Megin Nichols, CDC; (2) Nicole Martin, University of Cornell; (3) David Suarez, USDA (4) Jennifer Sinatra, USDA; (5) Nathan Anderson, FDA (6) Clay Detlefsen, National Milk Producers’ Association.

References and further reading

Pasteurization Kills Bird Flu Virus in Milk, New Studies Confirm | Scientific American

Updates on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) | FDA

FDA Research Agenda for 2024 Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Avian Influenza (as of June 24, 2024)

Animal experiments shed more light on behavior of H5N1 from dairy cows | CIDRAP (umn.edu)

Changing epidemiological patterns in human avian influenza virus infections - The Lancet Microbe

Raw milk is risky, but airborne transmission | EurekAlert!

Food Safety News and Resources

Our news and resources section has not-boring food safety news plus links to free webinars and guidance documents: no ads, no sponsored content, only resources that I believe will be genuinely helpful for you.

This week’s lowlight: Listeria deaths from plant-based milk (plus don’t miss the GFSI Consultation process)

Click the preview below to access it.

Food Safety News and Resources | July

22 July | Food Safety News and Free Resources | Salary and careers for food science professionals (report) | Outbreak and Recall: Plant-based milks for Listeria (Canada) | Recall: Reuseable water bottles for excess levels of BPA (France) | Recall: rice for ‘foreign object of rodent origin’ (USA) |

Did you know…

To finish off this week’s IAFP conference special, I want to share a few unexpected facts I learned, and my three favourite quotes from the event. Here they are in no particular order…

Meal toppers for pets are a thing (crumbly things you sprinkle on top of the bowl of pet food to make it more appealing).

Premium brands of raw pet food are using the very expensive processing technique high-pressure pasteurisation (HPP) for pathogen reduction in their products. This technique is most often used for high-value human foods like expensive juices or avocado purees, but ‘raw’ pet food has recently become the fastest-growing category in HPP foods. Another brand of raw pet food, which is not using HPP, is using fermentation techniques for pathogen reduction.

Despite hepatitis A and norovirus being major causes of foodborne illness, the majority of cases in wealthy countries are from person-to-person transmission, not from food.

Some scientists believe that norovirus can be transmitted through saliva, but others say the levels in saliva are very low and are probably the result of carry-over from vomiting, rather than from the virus replicating in salivary glands. The risk of transmission of the virus from saliva from, for example, sharing a drink, is not known.

As heard at the event…

“Don’t forget hazards are not risks” (Michelle Danyluk, University of Florida, talking about the difference between finding a pathogen in a field and it leading to consumer illnesses)

“I’m a regulator, we are boring people” (Preamble to a question from an attendee at the food fraud roundtable)

“This is a career where you get to ‘save the day’” (Clint Stevenson, North Carolina State University, talking about how to inspire students to consider careers in auditing and inspection)

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 New authenticity testing approaches for untargeted test methods, fish and ground almonds;

📌 Incidents in Zambia and India;

📌 Fake cheese allegations in Australia.