187 | New foodborne pathogen with links to 'safe' pesticides |

Plus, the FBI investigates a cyberattack on a poultry plant

This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

Bacillus velezensis, a pathogen you’ve probably never heard of

Food defence case study: Cleaning contractor commits cyber-sabotage

Throw-back: the 2024 cyber attack that put allergic consumers at risk;

Food safety news and resources;

Bacteria (just for fun);

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents.

Hello lovely readers,

Welcome to Issue 187 of The Rotten Apple, where I dissect a never-before-seen food-pathogen combination and share learnings from a recently revealed cyberattack on a poultry plant.

In this week’s food safety news, we’ve got two insect-related recalls, wine safety, patulin in apple juice and some good news for PFAS testing of bottled water.

And our food fraud news sees me getting excited by newly published research in food authenticity test methods.

Thanks for being here.

Karen

P.S. I’m thrilled that so many of you are choosing to renew your paid subscriptions (shoutouts to 👏👏Bruce, Victoria, Tom, Chris, Rachel, Andreas and Anna👏👏). Our reader retention rate is miles above industry benchmarks: thanks for the vote of confidence!

Paid subscribers get access to indexed articles, downloadable e-books, special supplements and recordings of live webinars and training sessions. Click the button to take a peek at the full archive of paid supplements, recordings and downloads.

(Another) foodborne pathogen you’ve probably never heard of…

If you’re a food science nerd, you’ve almost certainly heard of ropiness, a type of spoilage in baked goods such as breads and cakes.

Ropiness is a unique form of spoilage caused by spore-forming bacteria, mainly Bacillus species, whose spores survive baking and germinate in warm, moist conditions. It gets its name from the sticky, stringy, and slimy crumb in spoiled breads and cakes, which can include long, web-like strands when the product is torn open. Products affected by ropiness also have a fruity, rotting-melon-like odour.

Ropiness has been around since bread making began, and spore-forming Bacillus bacteria have been known as the cause of ropey bread for more than 100 years.

What’s new is that a Bacillus species which has never previously been associated with human illness or ropiness has been linked to an outbreak of gastrointestinal illnesses among people who ate rope-affected cakes in 2024.

Thirty-five people were sickened, developing symptoms including diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain within a few hours of eating the cake.

The cakes were supplied to a company for a celebration event covering multiple sites across two cities by a small retail bakery. After the celebration, the company reported “aberrations” in the cakes, presumably to a local health authority (sources are unclear). No illnesses were reported at the time.

Two days later, epidemiologists from the State Department of Health got involved, and two cases of illness were discovered. An outbreak investigation was launched with celebration participants surveyed and leftover cakes tested.

Interestingly, as part of the survey, workers who had attended the celebration were asked about the appearance, taste and odour of the cakes, and about the quantity of cake they had eaten. People who had not eaten the cake and people who had not become ill were also included in the survey.

Survey respondents described the cakes as discoloured, very dense and moist, off-tasting and undercooked or doughy. Some described a sweet pineapple odour.

When the survey responses were analysed, investigators found that people who had eaten cakes with signs of rope spoilage had experienced gastrointestinal symptoms and those who had not eaten such cakes had no symptoms, with a dose-response relationship between the quantity of cake consumed and symptoms.

Unsurprisingly, people who noticed the cakes had an odour ate significantly less cake than those who experienced no odour, eating 9 grams compared to 161 g respectively.

Bacillus velezensis was found in leftover cakes, but patient samples were not tested.

B. cereus was not found in the cakes.

The authors of a paper that describes the incident and investigation used a post hoc fault modes effect analysis (FMEA) to identify a list of factors that could have led to the proliferation of the B. velezensis in the cakes, including:

Increased spore loading during agricultural practices, such as through its use as an inoculant during wheat farming.

The high pH of the cake batter.

Too-short cook times.

Too-long cooling times and

a too-long period between preparation and consumption of the cakes.

About Bacillus velezensis

B. velezensis is one of four conspecific strains of B. subtilis, along with B. amyloliquefaciens, B. subtilis, and B. siamensis.

B. velezensis is used as a natural biocontrol agent for plant pathogens, including phytopathogenic fungi. It can be found in Syngenta’s ARVATICO and CERTANO agricultural pesticides.

The authors of the paper about the cake outbreak assert that B. velezensis endospores could have been present in large numbers in the flour used to make the cakes due to the use of biocontrol agents in wheat growing or storage, saying the endospores could have survived baking and germinated in the cakes after cooking.

They also discuss the under-cooked appearance of at least some of the cakes, speculating that undercooking could either support the survival of the endospores or give the cakes a water activity that was more conducive to the germination and growth of the bacteria compared to fully cooked cakes.

As with many Bacillus species, B. velezensis exhibits antimicrobial effects due to its production of antimicrobial secondary metabolites during growth. No other organisms were found in the cakes.

Is this really new?

B. velezensis is not a new bacterium, and its usefulness as a biocontrol agent has been extensively studied. However, its ability to cause human illness has not been reported until now.

The authors of the paper suggest that this outbreak was only identified as an outbreak because the victims were part of a larger event across 11 locations belonging to a single business. The symptoms were relatively mild and if the people had not all worked for the same company, they may not have attributed their illnesses to any particular event.

The fact that some people thought the cake was spoiled probably contributed to their ability to remember the event, their symptoms and the quantity of cake they consumed.

The epidemiological investigation surveyed people who did not eat the cake as well as people who did eat it, providing more confidence in the outbreak investigation results, in the absence of confirmed patient isolates of the bacterium.

Doesn’t this sound familiar?

I discussed a similar case in 2022 after researchers found a plausible link between food-borne illnesses and strains of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) commonly used in non-chemical pesticides and found on foods like tomatoes, bell pepper, rocket salad and endives.

Part of the reason this had been going unnoticed seemed to be because B. thuringiensis and B. cereus, a well-known foodborne pathogen, are closely related and it’s difficult to tell them apart using traditional mibrobial methods, meaning illnesses caused by B. thuringiensis, which is not officially recognised as a food-borne pathogen, may be attributed to B. cereus.

🍏 No way?! An unexpected source of microbial food-borne illness | Issue 23 🍏

What can we learn from this?

Bacillus bacteria and their enzymes are deliberately added to all kinds of microbial preparations, from probiotics to insecticides.

I once investigated an ingredient for a ‘chemical-free’ cleaning liquid, which contained enzymes from Bacillus subtilis. The product spec allowed for up to 105 viable organisms or endospores per millilitre. Those organisms and spores would have ended up in the cleaning liquid, which was marketed for use in food preparation areas, presenting a spoilage risk. Not good.

Big pesticide companies like Syngenta are likewise selling ‘natural’ treatments for crops and seeds that contain Bacillus species.

Bacillus thuringiensis, the active agent in Bt pesticides, was linked with two outbreaks of food-borne illness in 2022 and B. velezensis, the active agent in certain crop and seed treatments, has now been linked to illnesses and food spoilage.

For food safety professionals, the risks from crop treatments are difficult to predict and mitigate, especially for treatments that have been properly approved and correctly used. If such treatments result in potentially harmful food contamination, there is little that food safety systems can do in the way of prevention until authorities revoke the pesticide’s approval.

I would like to see more recognition by pesticide product developers and regulators that supposedly safe bacterial species used in bio-pesticide treatments for food crops could potentially cause food spoilage or illness in consumers.

In short: Bacillus velezensis, which is used in bio-based crop protection products was discovered to be the causative agent in a foodborne illness outbreak among consumers who consumed spoiled cakes 🍏 The species has not been recognised as a spoilage organism or pathogen previously 🍏 In 2022 another Bacillus species used in bio-pesticides, Bacillus thuringiensis was linked to two outbreaks in Europe 🍏

Source:

Brannen, D.E., Marks, J., Schairbaum, R. and Bokanyi, R. (2025). First report of the agricultural biocontrol agent Bacillus velezensis and foodborne outbreak due to rope spoilage in cakes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 91(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02570-24.

Food defence case study: Cleaning contractor and cyber-sabotage

Last week, U.S. media reported on a sabotage attempt on a poultry processing facility allegedly perpetrated by a former employee of the facility’s cleaning contractor. The case is before the courts.

This is a rare example of a cyberattack on a food facility that has been described in public documents.

The former cleaning company worker pleaded not guilty to charges related to unauthorised access to computers at the poultry processor, a facility where he had designed and maintained the chemical cleaning systems on behalf of his employer.

Prosecutors allege he used computer access to threaten the safety and integrity of the poultry plant, its workers, customers and consumers by altering flow rates and concentrations of cleaning chemicals and sanitisers in the facility.

The man, a senior electronics customer service support employee at the cleaning company, was responsible for designing and maintaining chemical dosing systems for the clients of the cleaning services provider, including the poultry plant. This gave him in-depth insider knowledge of the cleaning and sanitation systems, hardware and protocols used in the facility.

He also had access to the computer network that connected the chemical company to the onsite controls at the poultry facility.

It’s alleged the man illegally accessed the cleaning chemical system at the poultry plant with the intention of causing harm in August 2023, three months after his employment at the cleaning company was terminated.

They allege that over a period of six days he:

Disabled safety alarms;

Redirected alert/warning emails; and

Changed doses, flow rates and distributions of peracetic acid and sodium hydroxide through multiple stages of poultry processing.

“There were times that he increased the amount, there were times where he decreased that amount of chemicals, but he did that after he was fired”, said acting U.S Attorney, District of South Carolina.

In documents presented to the court during his indictment, prosecutors said that when the man’s employment was terminated in May 2023, he handed back his company credit card, keys, alarm codes and ‘password sheet’, but somehow maintained access to certain network and login capabilities.

He appeared to be motivated to get his former employer into trouble with their customer, said the prosecutor.

“There were times that he increased the amount, there were times where he decreased that amount of chemicals… he did that after he was fired” Brook Andrews, acting U.S Attorney, District of South Carolina (via Wis10)

None of the court documents or proceedings have revealed whether any physical harm was caused to the facility, its workers, products or customers. It is not known how the sabotage was discovered, but the acting U.S Attorney revealed the FBI was involved in the investigation and was responsible for the man being caught. The use of computers, after authorised access had been revoked, to try to create threats to public health makes this case a federal crime under U.S. law.

My guess: the alleged crime was discovered when someone at the poultry plant realised the chemical control system was operating in an unexpected way and alerted the chemical company or authorities, with the FBI ultimately getting involved.

Root causes

The cleaning company had the ability to remotely access and control the cleaning chemicals at poultry plants in two U.S states.

The cybersecurity systems at the cleaning company allowed a former employee to access those systems without authorisation. He was allegedly able to make unauthorised changes to chemical usage and override alarms and alerts that would have notified poultry company employees of the changes.

We do not know how the man regained or maintained access to the computer system after his employment ceased, though one cybersecurity expert I talked to said it was likely that the cleaning company simply did not think to remove his access credentials from their system.

The human resources people at the cleaning company, who collected the man’s ‘password sheet’ when he was fired, almost certainly had no idea that he could pose a threat to public health if he somehow retained access to their computer systems.

Could it really be that the oversight or ignorance of a human resources worker at a cleaning company allowed a near miss or actual food sabotage event? Unfortunately, it seems so.

Other possible points of access include…

easily guessable passwords – for example, the man could have guessed a co-worker’s password and logged in with their credentials;

weak firewalling for the computer network at the poultry processing facility or the chemical company;

knowledge about the login credentials of poultry company employees, obtained perhaps during training or commissioning of the chemical dosing system;

shared or generic logins known to multiple chemical company or poultry company employees.

Comments

There are so many people talking about the threats to food safety from cyberattacks, but very few examples of actual food safety impacts from cyberattacks.

The most well-known example of a cyberattack on a food company is the JBS ransomware attack of 2021, which caused disruptions to every JBS processing facility in the USA and to JBS supply chains in Australia. It caused supply chain chaos and huge economic losses, but consumers were not exposed to any food safety risk.

In issue 113, I explained that even when it’s possible for a hacker to gain control of food processing equipment, or circumvent security measures – for example by disrupting CCTV monitoring of critical activities - the results would almost always be either detectable – for example, food would spoil if refrigeration systems were tampered with - or require ‘boots on the ground’ actions inside the facility to achieve intentional adulteration.

🍏 Issue 113: Are Cyberattacks (Really) a Food Safety Issue? 🍏

This cyberattack, however, which involved chemical dosing systems, certainly appears to have had the potential to cause widespread harm to public health from a remote location. Let’s explore what the impacts could have been.

I can think of two ways this attack could have posed a threat to food safety: firstly by contaminating chicken at the facility with peracetic acid or sodium hydroxide, and secondly by preventing the correct cleaning and sanitisation of food handling equipment.

Peracetic acid and sodium hydroxide are both chemicals that you most definitely wouldn’t want to consume, but they are not radically toxic. If they were super-toxic, that is, if they were toxic enough to harm consumers in the event of an undetected spill or mistake with cleaning, they wouldn’t be allowed in poultry processing.

However, if applied to chicken in huge quantities, the chemicals could certainly cause harm to consumers. But they would also be easily detectable via the smell, feel and appearance of the chicken.

So, for me, any intentional adulteration with these cleaning chemicals would either have been present in hard-to-detect quantities that would be unlikely to cause harm or present in large quantities and likely to be detected before consumption: not a significant food safety risk.

The second scenario, preventing the correct cleaning and sanitising of equipment, would cause potential microbial contamination of the chicken. However, for this to result in a significant food safety risk would also require consumers to undercook or seriously mishandle the chicken before use.

That’s not to say such events would not be serious. Workers could be harmed, brands damaged, expensive recalls undertaken, product dumped and major cleanup efforts required if either of those scenarios had unfolded. Just saying the impact on consumers would likely be low.

Key takeaways

Food businesses are vulnerable to cyberattacks perpetrated through the systems of service providers like cleaning companies. In this case, an unauthorised person was able to access the cleaning chemical dosing and flow-management systems of a poultry processor through a computer network linked to a cleaning company.

Ignorance, error or inadequate systems at the cleaning company may have allowed a disgruntled employee to retain access to the food company’s chemical control software after his employment was terminated. The exact method of access has not been shared publicly.

Food businesses can be vulnerable to malicious acts through failures in the cybersecurity protocols of suppliers like cleaning service providers. Such failures can allow access to systems that intersect with food safety, such as cleaning operations.

The personnel responsible for access to computer systems at suppliers are unlikely to understand potential food safety outcomes for customers in the event of a security breach in their systems.

Supplier approval processes and food defence programs should consider the risks posed by suppliers with poor cybersecurity protocols.

In short: A disgruntled ex-employee of a cleaning company allegedly manipulated chemical dosing systems at a poultry processing plant through unauthorised access to a computer nework 🍏 Vulnerabilities in the cybersecurity protocols at the cleaning company may have allowed the alleged attack to occur 🍏 Suppliers and their computer systems can introduce vulnerabilities to food companies 🍏 Such vulnerabilities should be considered in supplier approval processes and food defence vulnerability assessments🍏

Sources:

Monk, J. (2025). ‘Disgruntled’ man sabotaged SC chicken plant, threatened public health, feds say. [online] The State. Available at: https://www.thestate.com/news/local/crime/article305396216.html [Accessed 5 May 2025].

Pilet, J. (2025). Food Safety News. [online] Food Safety News. Available at: https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2025/05/south-carolina-chicken-plant-sabotage-case-exposes-food-safety-gaps/ [Accessed 5 May 2025].

Popa, N. (2025). Grand Jury indicts Lexington man in connection with incidents at poultry plant. [online] https://www.wistv.com. Available at: https://www.wistv.com/2025/04/22/grand-jury-indicts-lexington-man-connection-with-incidents-poultry-plant/ [Accessed 5 May 2025].

Follow-up: Menu tampering cyberattack perpetrator sentenced

While we’re on the topic of cyberattacks, here’s a follow-up to an article I shared last year.

In Issue 165 I shared the story of a disgruntled ex-employee of Disney who accessed menu creation software for theme park restaurants and manipulated menus to make it appear that foods containing peanuts and other allergens were safe for allergic individuals to consume.

In January 2025 he pleaded guilty to knowingly transmitting a program, code, or command to a protected computer and intentionally causing damage and to committing aggravated identity theft.

Last week he was sentenced to three years in prison by a Florida court and fined almost $700,000.

Read more: 🍏 Food defence case study: cyberattack threatens allergic consumers | Issue 165🍏

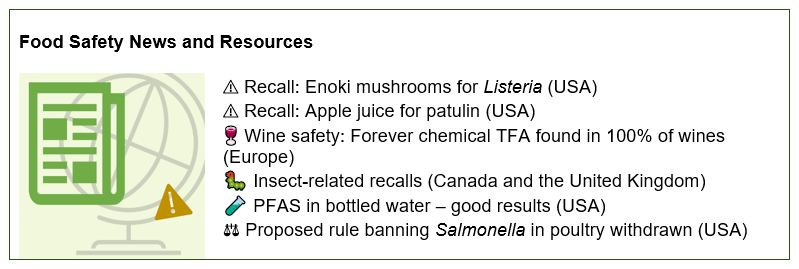

Food Safety News and Resources

Wine safety: You don’t hear that phrase often. But researchers in Europe have found the chemical TFA, which is a breakdown product of PFAS chemicals used in certain pesticides, in recently made wines from 10 European countries. Older wines contained no TFA. Find more about that and a link to the source in this week’s Food Safety News.

Also: Enoki mushrooms have been recalled again. This seems to happen at least every six months. This latest recall was prompted when food safety inspectors found Listeria in the pre-packaged but fresh mushrooms. That is, NOT because the distributor or packer had found it. Guess they weren’t testing. When will we learn?

Click the link below for these news items and more.

Bacteria (just for fun)

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, horizon scanning and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news, I share summaries of four innovative test methods for detecting food fraud. They are all examples of just how far we’ve come in food fraud analytical testing in the decade since I became involved in food fraud prevention.

It’s becoming increasingly possible to reliably distinguish between authentic and fraud-affected foods marketed with credence claims like grass-fed and organic. Even processing methods like HPP (high-pressure pasteurisation) are now able to be verified with analytical tests.

This week I also learned about a non-targeted test methodology that did not rely on verified authentic reference samples and still managed to detect fraud-affected samples with a high degree of accuracy.

Learn more and get links to sources below.

Also this week: shocking results in a survey of probiotic supplements.