189 | Money Laundering in Food Supply Chains | Bystander Intervention in Food Safety |

Plus, somewhere in Washington...

This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

Webinar recording: AI in food fraud prevention;

Bystander intervention in food safety culture;

The role of money laundering in food fraud;

Meanwhile, somewhere in Washington…;

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents.

Welcome, hello, hi!

It’s fantastic to have you here, for Issue 189 of The Rotten Apple. If you’re new here, I’m Karen and every week I collect the most interesting food safety and food fraud news from around the world just for you. My aim: to keep you up to date while respecting your inbox.

In this week’s issue, I get all philosophical about what it means to feel empowered to intervene when we see something that isn’t right. It’s a concept that’s important in food safety, food defence and beyond.

Also, I explore the links between organised crime, money laundering and cheese, and share a hand-washing sign that will make you smile.

As always, there’s food fraud news at the end of the issue, for paying subscribers.

Enjoy!

Karen

Webinar recording

Last week, I interviewed an expert to discover the latest in using AI for food fraud risk assessments. We had very good attendance over two sessions.

Click the preview below to access a recording of the second session.

Webinar: AI for Food Fraud - Early Fraud Detection for Raw Materials and Ingredients

Learn about how AI can be used to monitor emerging food fraud risks and create vulnerability assessments, in this webinar recording with Q and A. The Rotten Apple is not-boring food safety news and unique food fraud insights from an industry expert. Subscribe today and get a new perspective. No ads. No spam.

Bystander intervention in food safety culture

Choose your own adventure

Bystander intervention is a topic usually associated with bullying, harassment, racism or violence. However, it also has a role in preventing food safety failures.

When we see something that doesn’t look right, we start by asking:

1) Should someone intervene here?

2) Am I that person?

How we answer those questions determines whether we end up with a positive outcome or an escalating disaster.

Let’s consider bystander intervention in a food safety scenario.

Scenario

During the evening cleaning shift at a sandwich preparation facility, Ravi, a cleaner, notices that his coworker Lisa somehow has the wrong chemical coming out of her foamer.

What does Ravi do? (choose your own adventure)

Option 1: Ravi is worried but chooses to do nothing; he doesn’t want to embarrass Lisa or slow down the cleaning process.

Option 2: Ravi is worried but doesn’t want to say anything to Lisa, after all, she’s been working here for years, and he’s still new to the company. However, he decides something should be done, so he puts down his tools and goes to find the shift supervisor.

Option 3: Ravi goes straight to Lisa and tells her what he’s noticed.

What happens next?

Outcome for option 1: Ravi has said nothing. The cleaning shift finishes and the food contact surfaces aren’t properly clean, posing a food safety risk.

Outcome for option 2: Ravi spends 15 minutes trying to find the supervisor, who is busy on the phone outside. Lisa finishes her task and goes home, leaving the surface improperly cleaned and posing a food safety risk.

Outcome for option 3: Ravi tells Lisa what he noticed. She says she’s been feeling tired and wasn’t concentrating properly, and thanks him for pointing out the mistake before she had wasted too much time using the wrong chemical. She corrects the error and finishes the task, leaving all surfaces properly clean.

Interventions for hazard prevention

The scenario I just described is overly simplistic, but it makes a clear point: bystander interventions are a powerful way to stop problematic behaviour that poses food safety risks.

When I started work in food safety decades ago, the adage “If you see something, say something” was drilled into me by my mentors and manager.

But bystander interventions are complicated. Not everyone wants to say something when they see something. Power dynamics, fear of causing offence, lack of confidence and worry about being seen as a trouble-maker can all stop people from speaking up when they see something that is not right.

We can’t assume people will speak up if it doesn’t feel right in the moment.

I was reminded that a culture that encourages bystander intervention can be actively created during a recent training exercise with the Rural Fire Service (RFS) where I volunteer. One of the key foundations of RFS bush fire training is ensuring everyone will speak up if they see something that is dangerous or not right.

In the RFS, spotting hazards and communicating them to your teammates is part of the job, whether or not you think others have seen the hazard themselves. It’s a practice that undoubtedly saves dozens of lives on the fireground every year.

But the culture of “see something, say something” extends beyond the fireground and into the incident management teams of the RFS, too.

Mistakes made in the RFS radio room can be just as dangerous as mistakes on the fireground, costing precious time in an emergency, sending resources to the wrong location or providing ambiguous instructions to firefighters.

When I’m in the radio room, I not only expect my crewmates to tell me if I’ve made a mistake, but I am relieved if they do. It’s good to know everyone in the team is actively watching for communication errors, which are easy to make when a situation is heating up (literally!).

The culture in the organisation makes it easy for anyone to speak up without fear of ridicule, and easy for the person who's made a mistake to admit it without shame or fear of retribution.

Away from bushfires, a culture of “see something, say something” can prevent disaster on the sea as well. My boat-sailing friend tells every person who boards his vessel, “Watch out for hazards. Don’t assume I’ve seen something when I’m at the helm. If you see another boat, buoy or obstacle in our path, you must speak up. I’ll never make you feel silly for telling me about something that seems obvious. I want to hear if you see something. And don’t leave it too late: I want you to tell me straight away”.

A culture where it feels good and right to speak up loudly and often in the face of danger or miscommunication is good, but it’s not the norm.

In fact, prompt and suitable bystander interventions are relatively uncommon in public places, with typical response rates of less than 50 percent.

For example, a Japanese study of airway obstruction events for patients who ended up in hospital emergency departments found that witnesses only intervened half the time, despite airway obstruction being life-threatening and interventions significantly improving outcomes.

What encourages bystanders to take action?

In the context of sexual violence, research shows bystanders are significantly more likely to intervene if they believe their peers support such behaviour.

So it follows that if you can encourage a culture where it’s not just okay to intervene when a problem occurs, but actively encouraged, people will be more likely to act.

Perhaps just as importantly is how the intervention is received. Responses like “What would you know, you’re only new!” or “Of course I saw that burning branch was about to fall, I’m not an idiot” can stifle future actions.

It’s about team members….

Getting comfortable with “saying something”; and

Getting comfortable with receiving feedback.

Role-playing exercises and team training exercises with built-in intervention opportunities can help build these soft skills.

Other factors that affect whether bystanders will intervene include the number of other witnesses, with fewer witnesses increasing the likelihood of a response; the perceived severity of the problem being witnessed and the level of knowledge of the bystander.

Designated roles and responsibilities affect the likelihood of interventions too. For example, bystanders with a work role are significantly more likely to intervene in violent events than casual bystanders.

Scientists who study bystander intervention report that when there are a lot of people witnessing a problem, individuals are much less likely to take action compared to situations with fewer bystanders.

In a restaurant, whether or not patrons decide to respond to unsanitary food handler behaviour depends on the severity of the behaviour and their belief that an intervention will be effective (source).

The good news is that training in bystander intervention is very effective.

Tips for training

To improve bystander intervention behaviours in food safety scenarios deploy the following types of training:

Training that increases knowledge, so workers feel confident that what they are seeing is definitely a problem and not ‘business as usual’.

Food safety training that describes outcomes for consumers. This can increase workers’ understanding of the severity of a problem, with higher severity problems more likely to provoke a bystander intervention.

Role playing in teams, with a chance to practice intervening and receiving feedback.

Learning together in teams, where trainees are encouraged to correct each other. Small groups of less than 20 are recommended to allow for successful discussions (source).

Teach the five steps for successful bystander interventions, as described below.

Skills for bystander interventions need to be refreshed, with research showing that intent to intervene declines in the months after successful training (source).

Additionally, since it should be everyone’s role to say something if they see something, consider including this in job descriptions and required skill sets.

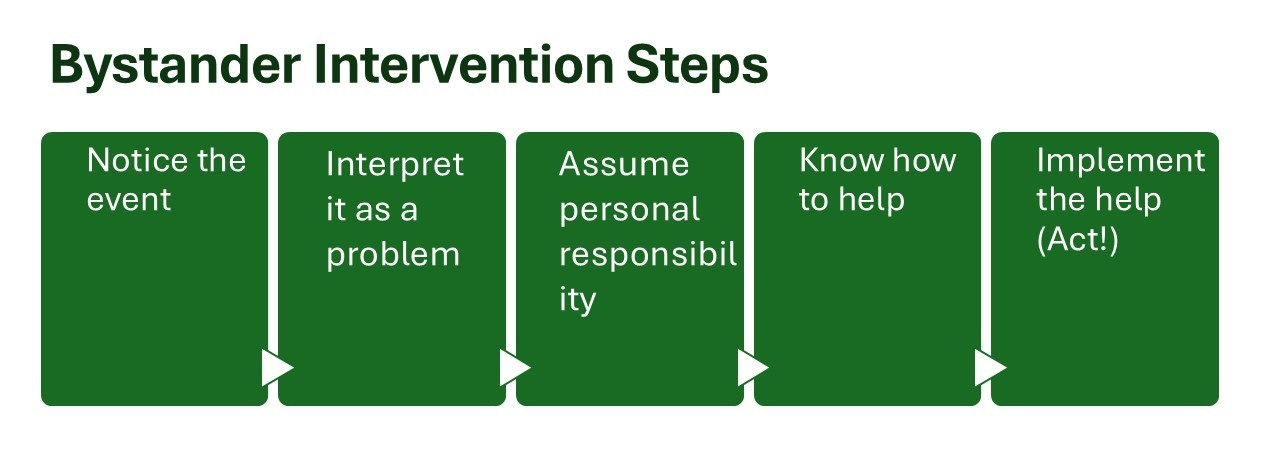

The 5 steps of bystander intervention

Five stages must occur for a bystander to successfully intervene when they witness a problem and these are described below. They are adapted from guidance published by Lehigh University, and are applicable to all potentially harmful situations, including violence, workplace bullying and worker safety as well as food safety.

1. Notice the Event: Other people in the area may be too busy to notice, while some may choose not to notice. Pay attention to what is going on around you.

2. Interpret It as a Problem: Sometimes it is hard to tell if what’s occurring really is a problem. If you’re unsure, err on the side of caution and investigate. Don’t be sidetracked by ambiguity, conformity or peer pressure.

3. Assume Personal Responsibility: If not you, then who? Do not assume someone else will do something. Have the courage and confidence to be the first.

4. Know How to Help: Never put yourself in harm’s way, but do SOMETHING. Help can be direct or indirect.

5. Implement the Help: Act.

In short: 🍏 A positive food safety culture actively supports the adage “If you see something, say something” 🍏 This concept, which encourages witnesses to speak up if they see something that is not right, needs to be explicitly taught and practised for the best outcomes, with frequent reinforcement 🍏

Further reading:

The role of money laundering in food fraud

Last year I wrote about the thefts of large quantities of luxury foods, which were perpetrated by criminals who posed as buyers from legitimate retail chains and ordered tens of thousands of dollars worth of cheese, smoked salmon and wine.

What happened to that stolen food? No one knows, although it’s suspected of having ended up in Russia, where trade embargoes and boycotts have disrupted legitimate supply chains for luxury foods.

Thieves steal food to make money. But they may also use stolen food as a way to launder money. Here’s how.

Money laundering is the process by which criminals disguise illegally obtained money using financial transactions that appear legitimate, resulting in ‘clean’ money that can be spent without attracting suspicion.

The food industry, with its extensive global supply chains, complex trade networks, hard-to-trace goods and pockets of cash-intensive businesses, provides ample opportunities for money laundering.

Many types of food supply chain businesses are used by criminals to launder illicit funds. Luxury restaurants, storage and distribution companies, brokerages, manufacturers and wholesalers all participate in financial transactions that involve the movement of large sums of money, often across international borders.

Money laundering can take the following forms:

Over-invoicing or under-invoicing of exports and imports, in which illicit funds are moved across international borders disguised as legitimate trade.

Cash purchases. Criminals can pay for supplies for restaurants and retail stores in cash. The revenue from selling these goods to diners or customers appears ‘clean’.

Shell companies, complicated business structures and fake suppliers. Money can be moved from company to company, mimicking legitimate trade without goods changing hands.

Falsified financial records: The value of stock inventories and incoming or outgoing goods can be falsified to hide the flow of illicit money. Salaries, vehicles and other employee disbursements can be used to move money in ways that appear legitimate.

Side bar: A network of interlinked companies that were posing as unrelated to each other was used in a large-scale international fraud in organic grain perpetrated in 2016 and 2017 (Read the deep dive here).

Money laundering can result in unfair trading environments for legitimate food businesses, which must compete using legally procured supplies paid for at market prices.

Operators that launder money using food businesses are thought to be significantly more likely to commit other forms of food fraud, such as relabelling of expired food, which poses a risk to consumers.

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of money laundering in food is the cost to governments, which lose much-needed tax revenue when money is laundered.

Stolen cheese and money laundering, a hypothetical

In 2024, criminals who impersonated a buyer from a French supermarket stole £300,000 worth of speciality English cheese. Could that cheese have been used for money laundering?

Perhaps yes. Here’s how it could work.

Note this is purely hypothetical, I have no inside knowledge of this supply chain or incident, and I make no allegation that such activities occurred.

The cheese is stolen by criminal organisation A.

The cheese is shipped across one or more international borders, making it harder to trace the cheese.

Organisation A pays the shipping company with money gained from criminal activities (‘dirty money’).

Organisation A sells the cheese to organisation B, which pays with ‘clean’ money.

Organisation A now has ‘clean money’.

Alternatively, organisation A sells to organisation C, another criminal organisation with links to organisation A.

Organisation C buys the cheese from organisation A with dirty money, perhaps for an inflated price, then sells the cheese to legitimate merchants.

Organisation A has received the money from C through a legitimate-looking business transaction. It has ‘clean’ money.

Organisation C receives money from legitimate cheese merchants. It has ‘clean’ money.

Main source: Fernando, P (2024). How money laundering is contaminating the food industry. Sunday Observer, Sri Lanka. Available at: https://www.sundayobserver.lk/2024/11/17/business/37757/how-money-laundering-is-contaminating-the-food-industry/

Read about big food thefts of 2024 in 🍏 Anatomy of a Food Crime | Issue 166 🍏

Meanwhile, somewhere in Washington…

A LinkedIn connection posted a photograph he took in a cafe washroom in the U.S. State of Washington yesterday.

I love this!

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, horizon scanning and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 Peanut in garlic, hmmm;

📌 Test method for honey;

📌 Learnings from the EU Annual Report Alert & Cooperation Network;

📌 Incidents affecting fish, rice, tea and functional foods.

Peanut in garlic: is this a fraud issue?

In 2017 or 2018, there were recalls in the United Kingdom due to the presence of peanut protein in garlic powder from China. It was possibly due to fraudulent adulteration, perhaps from the use of ground peanut shells as filler, rather than accidental contamination.

Two weeks ago, there was a recall and a market withdrawal in Ireland due to peanut protein in garlic powder from Lebanon and China, respectively. It seems eerily similar.

If you purchase garlic powder, be vigilant.

https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/rasff-window/screen/notification/760575

https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/rasff-window/screen/notification/759572