This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

5 Compelling food fraud pictures

Food safety news roundup

Packaging corner: risks from epoxidised soybean oil and updated EU regs

My friend ate fugu!

Food fraud news, horizon scanning and recent incidents

Happy Monday, food champion,

Welcome to Issue 190 of The Rotten Apple where I delve into my files and dig up a collection of food fraud photographs for us to explore together.

This week’s food fraud news features a new method used to rank the food fraud vulnerabilities of 105 countries.

Also this week: an update for packaging professionals, a link to this week’s food safety news, which contains good news about pesticide residues in food, and a first-hand account of eating fugu, the deadly pufferfish dish.

Enjoy,

Karen

P.S. Welcome and shoutout to 👏👏 Chelsea 👏👏 who became a paying subscriber last week, saying she did so "Because the work you do is valuable, the research you conduct deserves support, and I'm very interested in the food industry because my work is based on Product Development and Innovation, specifically in the food industry." (Translation from Spanish). Thank you, Chelsea.

This is Food Fraud

Food fraud in pictures

We’ve come a long way with food fraud awareness since I started working on the subject in 2015. More and more food industry people now recognise that food fraud is a genuine threat to the safety and integrity of our food supply.

But few of us have actually seen food fraud up close. Part of the problem, of course, is that food fraud, by its very nature, is hard to spot.

This week, I’m sharing my collection of favourite food fraud images, from around the globe and across the decades, starting with turmeric extract.

Turmeric extract

Figure 1 shows a simulated “fraud” which demonstrates dilution-type fraud in turmeric extract. The sample on the right contains about 25% curcuminoids. The sample on the left has been diluted with cornstarch and contains about 10% curcuminoids.

Dilution fraud occurs when a food is diluted with material that costs less than the food to increase profits. Examples include fruit juice, milk or wine adulterated with water and sawdust added to tea powder.

Common fillers for botanical extracts are maltodextrin, starches and other materials with a cellulose base, such as carboxymethylcellulose.

Fillers and flow agents are added legitimately to botanical extracts like turmeric extract to achieve a flowable powder. However, some suppliers add more filler than needed, and this allows them to sell the same quantity of the pure extract for a higher price.

There are no legal definitions for botanical extract purity in many jurisdictions, so the amount of filler or flow agent is not regulated. If the concentration of filler or flow agent is not specified and checked by purchasers upon receipt, then the supplier may be tempted to add too much.

Purchasers of botanical extracts use visual checks, HPTLC and colour specifications as an ‘early warning signal’ when receiving material. Extracts that have a lighter colour than expected warrant further investigation, although it’s worth noting that turmeric is also vulnerable to adulteration with colourants such as metanil yellow and lead chromate.

Source: Turmeric Extract | Blake Ebersole

Saffron

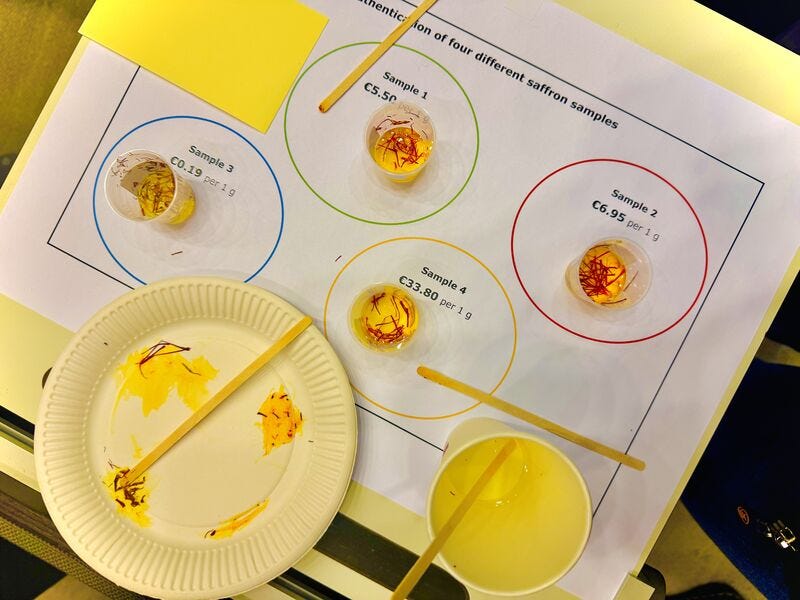

Figure 2 shows a simple authenticity indicator test for saffron (Crocus sativus L.), using water. The test provides a visual indication of potential adulteration or substitution and can be used to decide which samples require further investigation.

When water is added, real saffron releases a dark golden colour over a period of a few seconds while maintaining intact stigmas. Suspicious samples release significant quantities of colour in less than 1 second, lose their structure and show evidence of non-stigma materials.

In this test, conducted by students in a food fraud course at Wageningen University on samples purchased from local stores, three of the four samples appeared inauthentic, including the most expensive samples.

Sample 3 (blue circle) was confirmed to be safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), which is substituted for, or used to adulterate, saffron, due to its similar appearance. The photographer did not share which was the genuine sample.

Source: Saffron Test | Devi M Krishna

Learn more about saffron fraud: 🍏Saffron Fraud | Issue 31 | The Rotten Apple🍏

Paprika

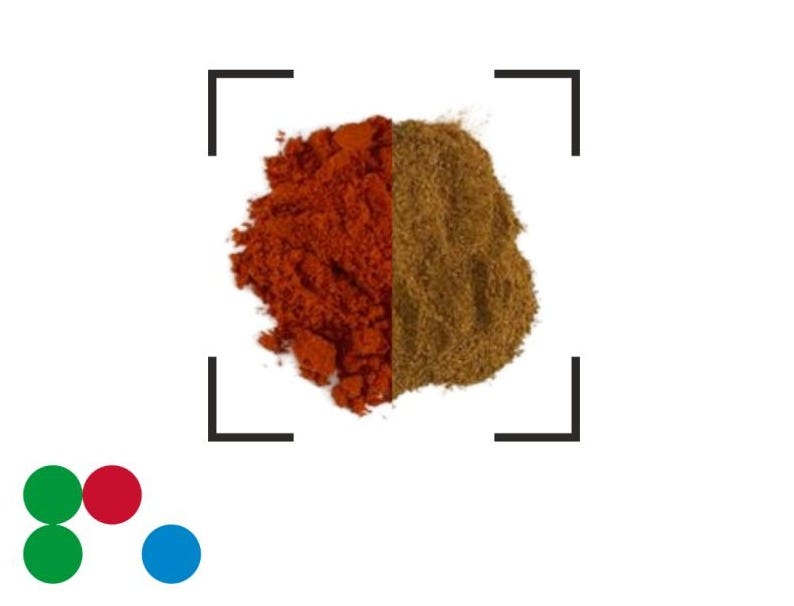

Figure 4 shows adulteration-type fraud in two paprika products imported to the United States. The sample on the left contained very high levels of the oil-soluble dyes Sudan I and Sudan IV. The sample on the right contained the natural colour annatto (E160b).

These samples were tested by the New York State Food Lab in 2014.

Adulteration-type fraud is when something is added to food to increase its apparent value without being declared to the purchaser. Adulterants can be unsafe for consumers and often conceal quality defects. Examples include textile dyes added to spices to make them appear fresh and flavoursome, and melamine powder added to milk to boost its apparent protein content.

Sudan dyes are textile dyes which are carcinogenic and not approved for use in food. In 2024, there were 8 notifications for Sudan dyes in foods imported to the European Union. The foods included curry powder, chilli powder, palm oil, sumac powder and cheddar cheese powder.

Adulteration with unapproved dyes sometimes accompanies another type of food fraud in paprika: dilution or substitution with ‘spent paprika’.

Spent paprika is a dull fibrous material left over after paprika oleoresin - the coloured and flavoured part of paprika spice - has been extracted from the fruit (Capsicum annuum L). Paprika oleoresin has a high value and is used legally as a natural colouring agent in cheese, juices, sweets and sauces.

When spent paprika is added to whole paprika, or used in place of whole paprika, the resulting mix has a dull colour. Fraudsters then add illegal colourants such as Sudan dyes to the mixture to make it appear genuine.

Sources:

Tarantelli T., Sheriden R. (2016) Toxic Industrial Colorants found in Imported Foods. Available online at: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/industrial-dye-presentation-12-11-2015/60160214

Bia Analytical (2025) Why is Spent Paprika Not Paprika. LinkedIn. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/bia-analytical_adulterate-foodfraud-foodadulteration-activity-7313487808575250433-clM7/

Oregano

Figure 6 shows the similarities between dried oregano and other leaves used to dilute it.

Oregano is the herb most often affected by food fraud, and there have been several high-profile cases of consumer groups revealing food fraud in oregano, including in the United Kingdom in 2015, Australia in 2016 and the United States in 2017.

In the Australian tests, fewer than half of the 12 samples purchased from retail outlets were pure oregano. The others contained between 10 and 90 percent leaves from other plants, including olive leaves and sumac leaves. Tests in the United Kingdom and the United States of America showed adulteration in around one-third of samples.

Have things improved with oregano in the decade since?

Unfortunately, they have not. In 2020, oregano imported to Europe from Turkiye was found to contain olive leaves. Further testing revealed one-quarter of samples were affected. Two of the samples contained no oregano at all.

In 2021, the European Commission tested 1,885 samples of spices and herbs and rated oregano the worst performer for food fraud, with 48 percent of approximately 300 oregano samples affected by adulteration, mostly with olive leaves.

And in 2024, the United Kingdom’s Food Standards Agency found 13 percent of 30 samples of oregano to contain leaves other than oregano, mostly olive leaves, at levels of up to 25 percent.

Learn more about oregano fraud: The Billion-Dollar Oregano Scam You Didn’t Know About | Food Unwrapped | Youtube

Comment

Food fraud affects many types of food and drink, but I only had images of herbs, spices and botanicals in my collection. That’s not a coincidence. Herbs, spices and botanicals are some of the worst-affected foods for food fraud.

I would have loved to have shown you photographs of food fraud in other commonly affected commodities such as seafood, honey, olive oil and dairy foods, but unfortunately, fraud-affected versions of these foods look almost identical to the real thing, and so photographs are both rare and unhelpful.

🍏 What about you? Have you got any food fraud photographs to share? If so, I would love to hear from you. Write to me by replying to this email, or by direct message on LinkedIn 🍏

Food Safety News and Resources

In this week’s food safety news: Good news for pesticides in food, 40 free videos for training, a cucumber recall and more…

Click the preview box to read.

Packaging Corner

Packaging professionals: it’s been ages since I’ve done a packaging corner for you, because nothing interesting and packaging-related has come across my desk until now.

Epoxidised soybean oil in packaging materials and printing inks

Seen in an online forum: a packaging manufacturer was worried after a customer called them out for not including epoxidised soybean oil in an allergen declaration.

Epoxidised soybean oil is used as a plasticiser and stabiliser in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) products such as cling films, gaskets for jar lids, and food-grade containers, to enhance their flexibility, durability, and heat resistance. In printing inks, it functions as a barrier and improves adhesion.

Epoxidised soybean oil is a non-toxic and environmentally-friendly alternative to traditional plasticisers like phthalates, which have been subject to restrictions due to their ability to interfere with human hormone systems.

In ink, epoxidised soybean oil is used as a non-toxic, biodegradable alternative to petroleum-based ink components.

With respect to allergens, soybeans are a common human food allergen and foods containing soybeans and their derivatives must carry warning labels. However, highly refined soybean oils are considered unlikely to cause allergic responses because of their very low protein content. As such, highly refined soybean oils are excluded from mandatory allergen labelling requirements in some jurisdictions.

Epoxidised soybean oils are not the same as highly refined soybean oils. The epoxidation process can be conducted on crude or refined soybean oil. When made from crude soybean oil, the epoxidised oil may contain residual proteins.

A packaging material containing epoxidised soybean oil or printed with ink containing epoxidised soybean oil is unlikely to pose a risk to allergic consumers, but the risk varies with the packaging type, food type and food storage and preparation processes.

Packaging suppliers should declare the presence of the epoxidised soybean oil in their materials to food manufacturers so that purchasers can perform their own risk assessments based on the type of food, surface area exposed to the material, shelf life, results of soy protein residue tests and relevant regulatory requirements.

EU regulation changes for plastic materials for food contact

The European Union recently amended regulations for plastic materials for food contact, recycled plastic materials for food contact and good manufacturing practices for such materials.

The changes include new requirements for the marketing of recycled plastics for food contact, labelling rules for reusable articles, compliance documents and changes to food simulants.

The changes came into force in March 2025 and are set out in Commission Regulation (EU) 2025/351.

Amended regulations:

Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food

Regulation (EU) 2022/1616 on recycled plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with foods

Regulation (EC) No 2023/2006 on good manufacturing practice for materials and articles intended to come into contact with food

Repealed regulation:

Regulation (EC) No 282/2008

My friend tasted fugu!

Not gonna lie, most of what I know about fugu was learned from watching The Simpsons.

Fugu is a Japanese delicacy made from pufferfish, known for its unique flavour and because the fish contains lethal doses of the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin. Chefs must undertake rigorous training and licensing before they may prepare fugu because only certain parts of the fish are safe to eat.

Up to six people die each year in Japan from eating fugu, almost always after catching and preparing it themselves.

An associate from Australia travelled to Japan last year and shared his experience with fugu sashimi. I was surprised and intrigued that he chose to eat it, given that he has been working in food safety for 25 years!

He explained that the restaurant, a small but high-end sashimi restaurant with an excellent reputation, was meticulously clean with a well-trained chef-owner and an obviously top-notch food safety culture, judging this was enough to stake his life on.

But what did fugu sashimi taste like?

When asked if it was tasty, he said: “Yes very, creamy texture, sweet, soft, bit like sashimi kingfish but I’d say better. I thought it might just be the danger factor but no, for me it was very good.”

“I thought it might just be the danger factor but no, for me it was very good.”

“Poison. Poison. Tasty fish”. This clip from The Simpsons is not safe for work.

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, horizon scanning and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

Food Fraud Vulnerability Index 2025: Countries Most at Risk for Adulterated Foods

A scoring method, based on metrics described in a peer-reviewed paper (van Ruth, et al, (2017)) combined with an analysis of scientific, economic and public health data from peer-reviewed journals and industry reports, and data from reputable sources such as the United Nations, has been used to rank the food fraud vulnerabilities of 105 countries.

The method considered opportunity, motivation and control measures for each country. Sub-factors of these, such as food price volatility, GDP per capita and food safety capacity, were assigned weighted scores with all scores combined and standardised.

The results? The countries with the highest vulnerability to food fraud, according to this method, are