Seed oils: food safety issue or beat-up?

Gritty food fraud

STEC in flour

5 Food Safety Quick Bites

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents.

Hello lovely readers!

My mission is to serve a global audience, and if a food safety story fills me with enough awe and wonder to stop me in my tracks and think, “yep, this is something we’d all want to know about”, then I sit down to share it with you.

I hope that somewhere among the dozens (hundreds?) of articles you’ve read, some of them have made you go wow, because that’s what I strive for every week.

Because this publication tries to be global, I’ve mostly chosen not to commentate on the current state of food policy disruption in the USA. But a recent post by the respected US nutrionist Marion Nestle about MAHA – Make America Healthy Again – reminded me about the current demonisation of seed oils in popular American culture.

What is going on with that?!

So today’s big article is dedicated to seed oils. What do policy-makers and influencers mean when they talk about seed oils (exactly)? Why are they supposed to be so terrible all of a sudden, and where has this new idea come from?

Also this week, follow-ups from last week’s sugar fraud news and STEC report, plus 5 short food safety stories and plenty of food fraud news.

Karen

P.S. Shout out to 👏👏 Sander from Europe, Sule, Steve and ‘Compliance’ from South Africa 👏👏 for becoming paid subscribers. Thank you, I couldn’t make this newsletter without people like you.

Seed Oils - A Food Safety Issue or a Beat Up?

I get sugar and tobacco vibes when I think about the current kerfuffle over seed oils.

If you recall, the sugar industry set out to demonise animal fats in the 1960s and 70s and succeeded in making them dietary enemy number one for decades, successfully taking the spotlight off the harms caused by the overconsumption of simple sugars.

Today, influential people are publicly demonising seed oils in a way that reeks of a similar approach. If there is a sinister campaign at work here, it’s been mighty effective. The Make America Healthy Again policy includes prioritised actions against seed oils while other parts of the same government cut $1 billion from USDA for local food purchases for school lunches and food banks.

I can’t help wondering if there is a competing oil or fat industry going after seed oils? Or perhaps even a foreign government seeking to harm the health of Americans by encouraging a return to animal fats (newsflash: searches for “tallow” are up by 267% in the past year).

What are seed oils?

Seed oils are edible oils extracted from the seeds of various plants. The seed oils most often criticised are sometimes called the “hateful eight:” soybean, canola, corn, cottonseed, sunflower, safflower, rice bran and grapeseed, but other seed oils include linseed (flaxseed) oil and sesame oil.

In the US, soybean oil accounts for 60% of the market share of edible oils, with canola, corn and cottonseed at 16%, 5%, and 3% respectively.

Seed oils are made by crushing or grinding the seeds of plants to make meal, then heating the meal, followed by pressing or using solvents to extract crude oil. The crude oil is refined, with the refining processes often making use of chemicals or steam.

What’s all the fuss about seed oils?

The backlash against seed oils began to gain significant traction in about 2018, with misinformation spread by social media influencers and alternative health advocates who questioned the safety and health effects of these oils.

Claims about the toxicity of seed oils, their links to chronic diseases, and their alleged harmful components are now so prominent that the US government is formulating policy around them.

The key concerns of the anti-seed-oil lobbyists are described below.

Processing methods: Critics are concerned about the use of chemical solvents like hexane in oil refining processes, which they believe may leave trace residues in the finished oil.

However, a study of 40 oils from the Iranian market, including blended oils, sunflower oils, corn oils and canola oils, found they all contained less than the EU-regulated limit of 1 mg/kg, with the maximum amount found in a sample at just 42.6 µg/kg.

A different study of four oils found the sample of sunflower contained 2 to 3 times the limit for hexane, while corn oil, sesame oil and palm oil samples contained hexane below the 1 mg/kg limit. Residual hexane is likely to evaporate from oil during cooking.

High omega-6 content: Many seed oils are high in omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. While these are essential nutrients, a too-high ratio of consumption of omega-6 compared to omega-3 may cause health issues, including an increased risk of obesity and inflammatory disorders.

However, people who consume more seed oils have not been shown to have excess pro-inflammatory compounds or inflammation markers in their bodies. In addition, oils high in omega-6 can reduce the risk of heart disease if used in place of saturated fats.

Use in processed foods: Seed oils are used in highly processed foods, which are also high in sugar and salt, and unhealthy fats, further fueling concern.

So, are seed oils unsafe?

I understand consumers’ concerns with hexane residues in seed oils, and their possible links to inflammation. However, toxic effects from hexane are not expected at the less than 1 parts per million quantities found in seed oil.

In addition, if their consumption is balanced by a healthy intake of omega-3-containing foods, there is no evidence they can cause inflammation, cancer or heart disease.

In summary, there is no evidence they are unsafe for consumers.

To me, the current complaints about seed oils seem like the result of a well-coordinated campaign against them, perhaps begun by a competing industry. If that’s the case, the masterminds have hidden their tracks well, as I was not able to uncover any obvious links between the social media influencers promoting misinformation about seed oils and a source of financial support for the campaign.

Read more: Are Seed Oils Really Bad For You? | BBC (2025)

Follow-up: A gritty food fraud

If you’d asked me a month ago whether cane sugar was at risk of food fraud I would have told you it’s at risk of smuggling and illegal trading. But I would not have said it’s vulnerable to adulteration or dilution, because when you add material to granulated sugar, it’s easily detected by the purchaser.

I’ve changed my mind!

In last week’s food fraud news, I shared insider intelligence I received from a company that processes sugar in Canada. They had received two large shipments of bulk raw cane sugar from Brazil that contained significant quantities of sand.

The amount of sand, and information received from their sugar supply chain lead them to believe the sand was present due to food fraud.

It’s a weird kind of food fraud because the purchaser detected the fraud easily. Usually with food fraud, the perpetrators take measures to make sure the fraud is NOT detected, because the longer they can perpetrate a fraud the more money they can make with their frauds.

Reminder: Food fraud is deception perpetrated with food for the economic benefit of the fraudster. It’s not the same as food adulteration perpetrated to cause harm to consumers or businesses, a concept we call ‘food defence’.

The sand was causing major difficulties with receiving and processing the sugar, damaging the company’s equipment and clogging filters. The situation was so dire that the company’s engineers had to design custom-made vibrating systems to keep their processes operational.

Below you can see a picture supplied by the business, showing a thick layer of sand on the factory floor, deposited by water overflowing from the sand-clogged sieves.

Why did the perpetrators feel they could get away with such a brazen fraud, knowing it would be easily detected? Surely a sugar supplier would not risk their business reputation and the wrath of their customers by adulterating their product this way?

The answer is that the fraud seems to have been perpetrated by someone other than the sugar supplier…. someone who felt confident they could get away with the adulteration across multiple shipments.

There’s more information about how this fraud was likely perpetrated in last week’s food fraud news (for paying subscribers). Safe to say, it’s an interesting case, in which the sugar supplier and the purchaser both appear to have been victims.

Read more: Sugar alert (insider’s warning)! | Issue 197 | The Rotten Apple

Read more: Horizon scanning: sugar | October 2024 | The Rotten Apple

Follow-up: STEC in flour

Last week I wrote about Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in the context of a European Commission report about increased infections in Europe. I explained its prevalence, discussed case statistics and summarised the sources of STEC infections for the period of the report (2023). The outbreak foods in 2023 included raw (unpasteurised) milk cheese, ready-to-eat salad/ iceberg lettuce, buttermilk, and bovine meat.

What I didn’t talk about was STEC in flour.

Lucky for me, a fabulous reader wrote to tell me it should have been part of the story. The presence of STEC in flour has been top of mind in Europe since a deadly outbreak in France in 2022. More on that below.

The reader told me about the issues she and her colleagues face in the ingredient and spice industry in Germany when it comes to sourcing STEC-free flour.

Her company found it so difficult to find raw flour that was safe, no matter whether they looked at local, regional or Europe-wide sources, that they eventually switched to treated flour. This caused other problems because treated flour behaves differently to untreated flour from a water-binding perspective, and is presumably more expensive.

The German BfR has repeatedly detected STEC in baking mixes and dough samples, as well as in flour. The infective dose is very low, thought to be 100 colony forming units or fewer, and the bacteria can survive in wheat flour for two years.

Here are four outbreaks associated with flour and STEC

1: Frozen pizza outbreak, France (2022)

In 2022, France experienced its largest STEC outbreak, with 48 children sickened, and 2 killed after consuming frozen pizzas. The pizza dough had not been pre-baked, and final cooking had been insufficient to destroy the bacteria.

STEC O26 was isolated from both finished pizza and flour used to manufacture it. A nationwide recall was initiated, and manufacturing practices were overhauled to include adequate heat steps.

The case underscored that even cooked products may not reach temperatures high enough to reliably eliminate STEC.

2: Cookie dough outbreak, USA (2009)

In 2009, 77 illnesses across 30 U.S. states were traced to commercial prepackaged cookie dough. Most patients were adolescent girls who had consumed the product raw.

Extensive investigation pointed to contaminated flour as the probable source, though other ingredients were considered.

This led to a recall of 3.6 million packages, with the industry moving to manufacture “ready-to-bake” products as if they are ready to eat.

3: Pizza dough mix outbreak, USA (2016)

In 2016, 13 cases of STEC O157:H7 occurred across 9 states among consumers who had eaten dessert pizza made with a specific pizza dough mix, or breadsticks made with the mix. Eight were hospitalised; no one died.

Although the dry dough mix did not contain the outbreak strain of STEC, it did contain other enteric pathogens across multiple samples.

It’s suspected that the thicker dough used to make dessert pizzas might have predisposed it to undercooking, because the same mix was used for traditional pizzas at the restaurants where patients had dined.

4. Flour, USA (2016)

In 2016, flour produced at a flour mill belonging to a major brand was linked to an outbreak of STEC that sickened 56 people, causing 16 hospitalisations and one case of hemolytic–uremic syndrome (HUS). Many of the patients reported consuming homemade raw cookie dough in the days before they became ill.

The company recalled flour that had been produced during a four-month period. Approximately 250 other products containing the flour were also recalled.

Key takeaways for food safety professionals

STEC should be considered a hazard in dry goods such as flour. If it is present, it may have entered the flour during growing, transportation, or milling of the wheat. While STEC will not reproduce in flour, it will persist and can grow when the flour is added to products that contain more moisture.

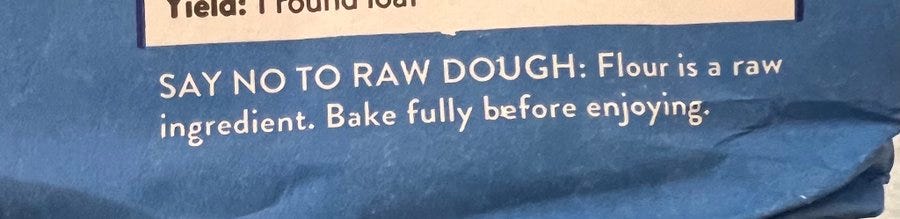

If your company uses flour in products that may be eaten raw, such as cookie dough or cake batter, you may need to use treated flour, which has been treated to eliminate STEC, to keep consumers safe.

STEC can be inactivated by a temperature of 70oC for 2 minutes when in moist foods; however, dry heat is ineffective against STEC in flour.

Undercooked baked goods and subsequent dusting of baked goods with raw flour also pose STEC risks.

In short: 🍏 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) has caused outbreaks from raw and undercooked foods containing raw wheat flour, including cookie dough, and undercooked or improperly cooked pizza 🍏 It can persist for at least 2 years in flour 🍏 STEC can be inactivated by 2 minutes of moist heat at 70oC but is resistant to thermal inactivation when in dry flour 🍏 Hazard analyses for flour and foods containing flour should consider the risks posed by STEC, even if the food is expected to be cooked before consumption 🍏

Learn more about STEC and flour

Read an excellent overview of STEC in flour, including an explanation of how it gets into flour and how to treat and prevent it here:

BfR Germany (2024) Escherichia coli in flour and dough – What is important for enjoyment without regrets?

Did you know?

Nanoplastics with a positive surface charge attract E. coli O157:H7, and the charged surfaces caused physiological stress, which stimulates more shiga-toxin production.

5 Food Safety Quick Bites

Listeria in enoki mushroom production

Listeria monocytogenes has been studied in an enoki mushroom (Flam mulina velutipes) production facility in China. Enoki mushrooms from China and South Korea have been recalled for Listeria contamination multiple times in the past few years, with recalls in Australia, the USA and Canada and an outbreak in the US that affected 5 people. The researchers found a high prevalence of L. monocytogenes in production facilities.

Mycotoxin in poultry - an emerging risk?

The mycotoxin cyclopiazonic acid was found in 20 percent of chicken breast muscle samples purchased from the Croatian market, the first time mycotoxin has been detected in fresh meat. Chicken livers also contained mycotoxins, and this was more frequent than in chicken breast. Levels were low, but more monitoring and research is needed.

Source: Mycotoxin Residues in Chicken Breast Muscle and Liver

Citrobacter braakii – an emerging food safety hazard?

Citrobacter braakii is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic bacterium within the Enterobacteriaceae family. It is commonly found in the environment in soil, water, and sewage, and can colonize the intestinal tract of humans and animals. Although usually benign, it can act as an opportunistic pathogen. New research suggests it may pose a risk in foods, with antimicrobial-resistant strains isolated from artisanal salami and soft cheeses. Three isolates were closely related to clinical strains.

Source: Citrobacter braakii Isolated from Salami and Soft Cheese: An Emerging Food Safety Hazard?

Another pathogenic Bacillus?

An analysis of an outbreak caused by Bacillus paranthracis from rice explores the characteristics of this spore-forming member of the Bacillus cereus group. The bacterium has rarely been implicated in foodborne outbreaks. Nine people were affected after eating at a restaurant where rice had been steamed in advance, left to cool naturally, then reheated and sold. The average time before illness onset was 3.5 hours.

Spore formers in UHT-treated plant-based milk ingredients

Researchers have examined plant-based raw materials for producing oat-, almond-, pea-, and rice-based drinks. Flours, flakes, protein isolates, and syrups were tested for their microbial loads.

There was a wide range of variation in viable cell counts and spore counts between the raw materials, with up to 8.5 log10 CFU/g. Rice and oat syrups that had been subject to UHT (ultra-high-temperature heating) contained spore levels of up to 4 log10 CFU/g. The researchers used the data to calculate the required log reduction to produce safe plant-based milks.

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, emerging risks and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 Methods for paprika, cinnamon, avocado oil, porcine meat

📌 Seafood fraud

📌 Warnings for beef and coconut oil

📌 Shocking survey results for retail samples, including oregano, Basmati rice, caffeine supplements, protein powders and more.