222 | How does cereulide get into infant formula? Which GFSI Scheme is Best? |

Plus, good news about auditors

This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

An insider’s view: How does cereulide get into infant formula?

Which GFSI certification scheme is best for your business?

Food safety news and resources

Good news re auditor requirements

Food fraud news and incident reports

Hello everyone,

Welcome to The Rotten Apple and happy Monday. Thank you to everyone who has renewed their subscriptions lately. Your ongoing support fills me with joy 😊.

In this week’s issue, I share some fascinating insights into cereulide, the bacterial toxin that caused a massive global recall when it appeared mysteriously in infant formula manufactured by Nestlé in December.

Plus, some practical guidance about food safety certifications and good news from the GFSI about auditor requirements.

As always, food fraud news is at the end for paying subscribers (who are excellent humans!). This week we’ve got good news for shrimp fraud in the US; bad news for ginseng; suspicious sausages containing possible cat meat (!) and allegations of retailer short-weighting in New York City.

If you like this newsletter, please take a moment to tell your friends and colleagues about it. Your shares make a genuine contribution and help grow our global food safety community.

Have a fabulous week,

Karen

Cereulide in Infant Formula (How, exactly?)

As reported in last week’s food safety news roundup, there is a monster-sized recall happening for Nestlé infant formula globally due to the presence of a bacterial toxin, cereulide. We don’t hear about cereulide very often, so I thought I’d do a little refresher on the topic.

Cereulide is the toxin produced by some strains of Bacillus cereus when they grow in starchy foods like cooked rice. It’s the thing that causes illness in “fried rice syndrome”, which occurs after cooked rice is left out of the fridge, allowing spores of B. cereus to germinate, grow and produce toxin in the food.

Cereulide is heat stable, tolerating high temperatures and low pH, allowing it to persist in foods exposed to temperatures of up to 150 oC.

Symptoms of cereulide intoxication are nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping. The onset is rapid, occurring 1–6 hours after eating contaminated food, and it usually resolves within 24 hours.

Cereulide is only produced in clinically significant amounts when there are high cell densities in the food (105 to 108 CFU/g). However, it is extremely potent, causing symptoms when present at levels as low as 0.01–1.28 µg/g.

In food production and home cooking, prevention of cereulide is simply a matter of limiting the growth of B. cereus in food by

rapidly cooling food after cooking;

maintaining chilled storage at ≤5 °C;

rotating chilled foods in storage and discarding those kept too long; and

for hot-holding (buffets, canteens), keeping food at ≥60 °C and discarding it after a maximum of about 4 hours.

Re-cooking or frying does not remove cereulide once formed, so practices like leaving cooked rice or left-over pasta at room temperature then ‘reheating thoroughly’ are unsafe, even if the organoleptic quality appears acceptable.

Did you know?

B. cereus is associated with two types of toxin: emetic toxin and diarrhoeal enterotoxins. Emetic toxins are toxins formed in food and cause illness when the toxin-containing foods are eaten. Cereulide is an emetic toxin. Enterotoxins are formed by pathogens inside the gastrointestinal tract rather than in the food.

Enterotoxic strains of B. cereus cause illness when they produce one or more enterotoxins as they grow in the intestine. The symptoms of enterotoxic B. cereus syndrome are different to emetic B. cereus: watery diarrhoea with abdominal cramps. Illness onset for enterotoxic B. cereus is 8–16 hours.

Cereulide in infant formula

Until now, outbreaks and recalls for cereulide in infant formula appear to be absent or extremely rare, although B. cereus has been isolated from powdered infant formula in numerous surveys and is capable of multiplying and forming toxins in reconstituted formula.

B. cereus gets into powdered infant formula through contaminated ingredients. B. cereus spores are widespread in soil, dust and plant materials, so ingredients of agricultural origin, such as starchy materials, plant‑derived oils and milk, carry the spores which can survive pasteurisation and drying processes.

In the current formula recall, however, it was not the presence of B. cereus spores in the formula that led to the recall. Instead, the cereulide was present in the formula, even before the milk was reconstituted.

It appears the source of the cereulide was an ingredient used in the formula. The cereulide was in the ingredient before it even reached the formula production facility.

Last week, the CEO of Nestlé recorded a video apology in which he explained that “the source was a specific raw material from one of our suppliers”.

Other sources have provided more clues about the ingredient, with Food Safety News stating, “Nestlé has tested arachidonic acid (ARA) oil and corresponding oil mixes used in the production of potentially affected infant nutrition products.”

Arachidonic acid (ARA) is an omega‑6 long‑chain polyunsaturated fatty acid naturally present in human milk and routinely added to infant formula together with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to provide specific fatty acids necessary for the proper development of brains, eyes and other organs.

ARA is added to infant formula in an ARA-enriched oil, not as a free fatty acid. The oil is added to the mix before emulsification and spray‑drying.

How could cereulide get into oil?

We’ve already learned that cereulide is a toxin produced when B. cereus grows in starchy foods. How could it have got into ARA-enriched oil?

Here’s one theory, proposed by an expert food safety microbiologist with an impressive resume, experience in fermentation and knowledge of the internal workings of microbial hazard analyses at multinationals, who wishes to remain anonymous.

S/he believes that cereulide was not flagged as a hazard in the oil because the food safety team that did the hazard analysis may have imagined the oil was produced in the traditional manner, by pressing oily plant materials.

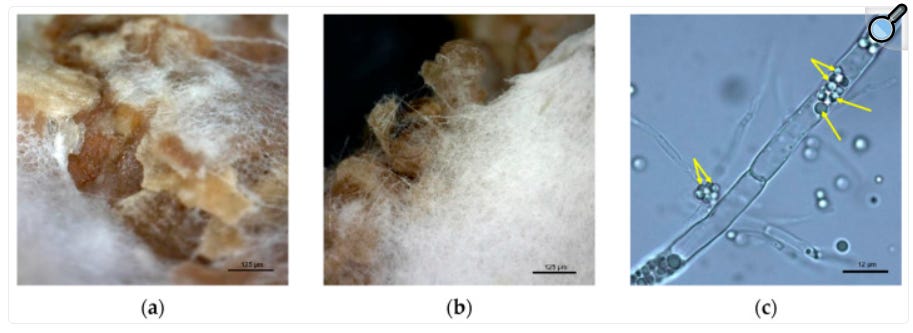

However, ARA-enriched oil is not produced like other oils, but is instead produced by fermentation: a triglyceride‑rich oil is extracted from the filamentous fungus Mortierella alpina and refined like a vegetable oil.

The expert shared that Mortierella alpina is difficult to culture. The fermentation is a fed batch process and is slow compared to bacterial fermentations. The fermentation substrate (the ‘food’ the fungus feeds on) can include oilseed press cake. Oilseed press cake is the solid residue left after oil has been mechanically extracted from oil‑rich seeds or nuts such as soy, canola and sunflower.

The cereulide was most likely present in the oilseed press cake used as a fermentation substrate, says the expert. It would have survived the sterilisation process that such materials are subjected to before being used as a growth medium.

Cereulide is hydrophobic, making it more attracted to oil than water, so if present in the substrate, it would disperse into the oil phase of the fermentation liquid, ultimately concentrating the toxin in the final ARA oil.

How was this missed? It’s possible that cereulide just wasn’t on the radar of the ARA producers, and so they did not test for it in their incoming substrate or outgoing products. And as we saw before, even expert food safety professionals could (wrongly) assume that oils can not be contaminated with bacterial toxins.

Final thoughts

We don’t know for sure if the cereulide in the recalled infant formula came from ANA-enriched oil – the only official word from Nestlé is that the source of the contamination was an ingredient from one supplier.

However, if ANA oil was the source, we now know how it could have become contaminated with a bacterial toxin. The route is quite convoluted!

Food for thought: What other fat-soluble toxins might find their way into fermentation-produced oils like ANA oil following a similar route? And what other foods and pharmaceuticals might be at risk from such a hazard?

In short: Cereulide is a bacterial toxin formed when the bacterium Bacillus cereus grows in starchy foods 🍏 Cereulide is extremely heat resistant 🍏 It causes vomiting and nausea when consumed 🍏 There have been no outbreaks from cereulide in powdered infant formula, although B. cereus is found in powdered infant formula and can grow and produce toxin in reconstituted formula 🍏 Nestlé, the manufacturer of the infant formula that has been recalled for cereulide says the source of the contamination was “a specific raw material from one of our suppliers” 🍏 Industry speculation suggests arachidonic acid (ARA) oil and oil mixes may be the sources of the cereulide 🍏 Cereulide could get into ARA-enriched oil if growth media containing cereulide was used in the fermentation process used to make ARA oil 🍏

Main source (other sources are hyperlinked inline):

Yang, S., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Jia, K., Zhang, Z. and Dong, Q. (2023). Cereulide and Emetic Bacillus cereus: Characterizations, Impacts and Public Precautions. Foods, [online] 12(4), p.833. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12040833.

How to Choose a GFSI Certification Scheme

A guide for food safety professionals

Selecting the right GFSI certification scheme for your business is more than a simple box-ticking exercise. It’s a strategic decision that impacts compliance, market access and operational efficiency. Getting this decision right means understanding your business, your markets, and the strengths and limits of each scheme on offer. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.

In this article, I explain the GFSI system and show food professionals how to choose the right GFSI scheme for their business.

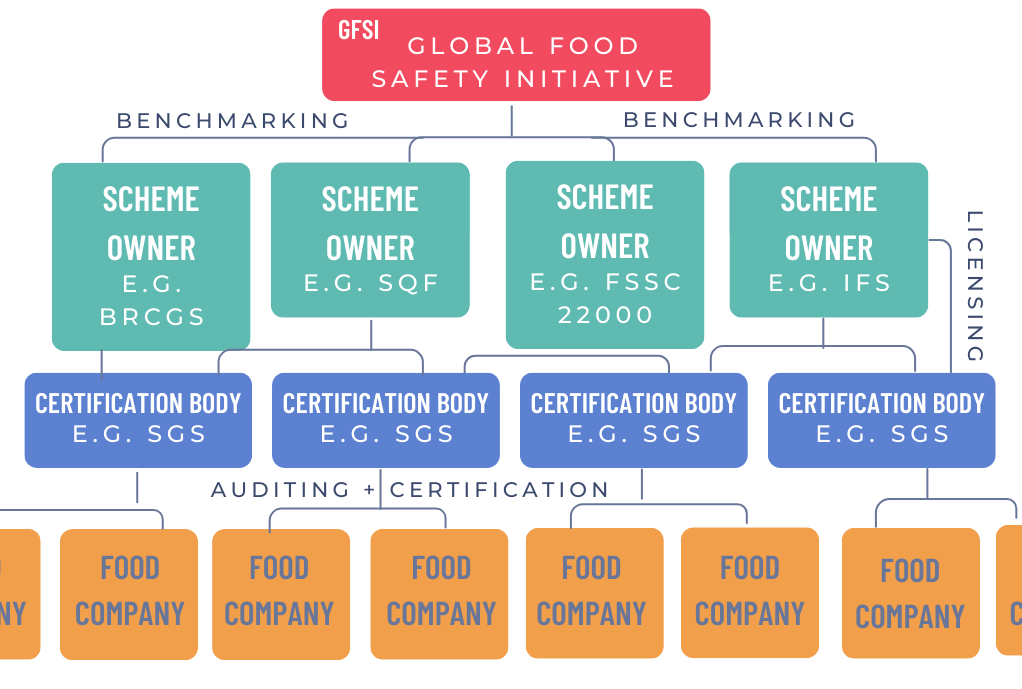

What is GFSI?

The Global Food Safety Initiative – or GFSI – is a coalition of retailers and manufacturers that acts as a referee, benchmarking various food safety standards so that they can be used interchangeably by food purchasers globally.

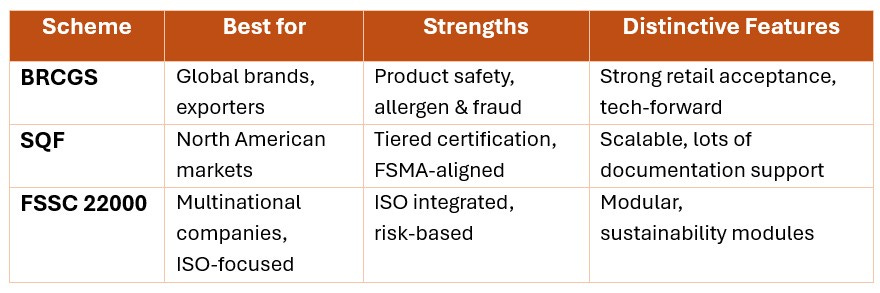

There are many GFSI-recognised schemes, but the most widely adopted food safety schemes include the BRCGS (British Retail Consortium Global Standards), SQF (Safe Quality Food), and FSSC 22000 (Food Safety System Certification). Each has a distinct focus and benefits.

BRCGS is globally prevalent and common in the United Kingdom and Europe. It offers a prescriptive, product and process-focused standard emphasising product quality, allergen management, food defence and fraud prevention. Its detailed requirements support companies that need to demonstrate strong product integrity and traceability to global retailers.

SQF is a tiered program widely used in North America. It aligns closely with the US Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and offers scalability with different certification levels, accommodating companies at various stages of their food safety journey.

FSSC 22000 integrates ISO 22000 standards and sector-specific pre-requisite programs (PRPs) into a modular system. It appeals to larger, multinational companies seeking comprehensive management system integration with food safety and other corporate programs like environmental or occupational health. FSSC 22000 emphasises risk-based preventive controls and continuous improvement.

Other recognised schemes include IFS and GLOBALG.A.P.

What should guide your choice of scheme?

Market and customer demands: Know where your customers are and what they expect. If you supply major retailers in North America, SQF is often required, while BRCGS is the go-to for Europe and the United Kingdom. FSSC 22000 appeals to companies operating across multiple countries who value its ability to integrate with ISO standards.

Business maturity and complexity: Match the scheme to your operation’s maturity. Less mature sites – those with fewer formal systems and with more need for explicit guidance – may do better with schemes that have more prescriptive standards. For example, BRCGS, SQF and IFS have highly specific requirements and a scoring or grading system which together provide a roadmap to compliance. Conversely, well-established and complex companies may prefer FSSC 22000, which provides more flexibility and expects the site to “own” its performance without relying on a grading score.

Certification body availability and audit approach: When choosing a scheme, it’s important to consider the local availability and reputation of accredited certification bodies. If your chosen scheme isn’t well supported in your region, you may experience problems with audit scheduling, costs and ongoing support. All schemes require annual audits by accredited third parties. BRCGS and SQF audits are process and product-oriented, while FSSC 22000 audits emphasise management system performance and continuous improvement.

Budget: Certification costs vary widely, and they are more dependent on the certification body, local auditor availability, auditor travel time/distance and the complexity of your business than the scheme. Audit fees can range from USD2,000 to USD9,000 for a single site, and this does not include preparation costs borne by the food business. In addition, there are scheme owner fees ranging from USD100-1,200 per year. It’s advisable to get quotes from a number of certification bodies to understand costs as they relate to different schemes.

Practical steps to selecting your scheme

Map your current markets and growth ambitions to prioritise those schemes most accepted or required by current and future customers.

Consult certification bodies, auditors and consultants for insights relevant to your industry sector, business complexity and location.

Assess your internal food safety program maturity and existing management systems to determine the best fit.

Understand the ongoing costs of audits, scheme fees and internal labour associated with maintaining certification, and get quotes from different certification bodies before committing.

Key takeaways

Choosing a GFSI certification scheme is about more than market access. It’s about knowing your customers’ expectations, your internal capability, and setting your business up for steady, sustainable success in food safety.

There is no right or wrong scheme. Pick the one that fits your operation best, and use it to build trust, resilience and confidence.

Our food safety news is expertly curated (by me!), so you get only the most interesting, focused information from around the globe. Click the link below to view.

Food Safety News and Resources | January

19 January 2026

⚠ Cereulide recall: illnesses reported (Brazil)

🏺 Unusual recall: Sea moss gel for potential botulism

⚠ Unusual recall: Uncooked beef burger meat patties recalled for E. coli O157:H7 (Canada)

🦠 STEC E. coli prevalence is low (France)

📗 New shelf-life guidance for Listeria in ready-to-eat food (UK, Europe)

🎓Webinar - Food Safety Certification: Your Gateway to Major Retail Partnerships, 21st January

Follow-up: Auditor competencies under GFSI (good news)

There’s been an update – or a change of mind – in the GFSI requirements for auditors.

Last year, there was a huge outcry over the release of new auditor requirements under proposed updated GFSI benchmarks.

The new requirements would have made it impossible for people without a food science or related university degree to perform audits against GFSI-recognised standards.

Now, GFSI has backpedalled on that issue.

Specifically, they’ve said:

“C. Clarification on Benchmark Requirement 4.9

Table 1, column 3 requires auditors to hold a degree in discipline, or, at a minimum, to have successfully completed a relevant higher education course or equivalent. The inclusion of “or equivalent” is deliberate to provide flexibility.

GFSI emphasises that this benchmark requirement is not intended to exclude auditors who have developed competence through professional training, industry qualifications, and relevant experience.”

What this means:

1) Experienced auditors and professionals with suitable industry experience will NOT be excluded from auditing by the new GFSI benchmarks, contrary to what was previously reported.

2) The worldwide food auditor shortage continues, but with this change, the GFSI won’t be directly pouring fuel on the fire. Good news!

Read more: GFSI Unlocks Benchmarking for BMRs v2024 with New Governance Framework - MyGFSI

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 Good news for “local” shrimp

📌 A review of ginseng authenticity

📌 Cat meat in sausages?

📌 Retailer weigh scale issues, African swine fever pigs used to make pâté and more…

Good news for “local” shrimp

In 2025, we reported on testing of shrimp described on restaurant menus as “locally caught” or similar, in the Gulf Coast region of the United States. The incidence of provenance fraud was high, with 96% of restaurants in the cities of Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg, Florida (n = 44) found to be committing “shrimp fraud”.