Issue #57 | Drain cleaner and olives | Pesticides in organic food | Snackfood Spiders

2022-09-26

Olives and drain cleaner

Pesticide in organic foods - a food fraud indicator?

News and Resources Roundup

Just for fun: the snack company that loves spiders

Food fraud incidents and horizon scanning updates from the past week

🎧 On the go? Listen to me read out today’s email. Get access to audio with a free trial subscription, at the bottom of this email 🎧

Hello, buongiorno!

Welcome to Issue #57 of The Rotten Apple, an inside view of food safety, food authenticity and sustainable supply chains for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors.

As always, I’m excited to be bringing you food safety and food fraud news from around the world. And right now this email is literally coming to you from around the world. I am travelling (and doesn’t it feel good, post-pandemic to be out and about?!).

My travels in Italy inspired me to learn a little about olive processing this week. Also this week, some excellent resources for food experts who need to develop ESG (ethical sustainable governance) programs, and pesticides found in organic foods, again.

Paying subscribers also get food fraud news from the past week, including a link to the story of a business owner who has been accused of knowingly selling grape and apple juice with harmful levels of contaminants like arsenic and storing juice outdoors “for years”, leaving it exposed to the elements, before selling it.

I hope you enjoy this newsletter. And your week,

Karen

P.S. Need more info about paid subscriptions? Click here. Or….

Drain Cleaner and Olives, a Match Made in Heaven

I’ve been admiring all the beautiful olive groves in Italy during my travels. So I thought it was time to learn about how the inedible, horrible-tasting olive fruit is turned into delicious table olives that we can enjoy with our aperitivi.

It seems there are three ways to ‘cure’ olives, though please leave a comment and correct me if I have got it wrong, definitely no expert here!

To make olives edible, you can

Soak them in brine for months, or

Soak them in lye for a short time, or

Perform a Greek-style dry cure where the olives are layered in rock salt.

All three methods work by removing the bitter agents from the olive flesh.

The lye method is interesting for food safety nerds. Lye is sodium hydroxide, or caustic soda, and is the main ingredient in drain cleaner. You definitely can’t (shouldn’t!) eat or drink caustic soda!

So how, then, is food made with caustic soda safe to eat? The short answer is that lye is not toxic, just corrosive. In fact, if you mix sodium hydroxide with stomach acid (hydrochloric acid), you get plain old table salt (sodium chloride) and water.

Lye is used to make pretzels - it helps to form the brown crust - and in the production of tortillas and corn chips, where it allows the corn to be more easily ground, as well as improving the nutritional value and flavour.

In olives the alkaline nature of the lye speeds up the curing process.

Where on earth did ancient olive-growers get caustic soda?

People have been processing olives to make them edible since perhaps around 3,500 B.C. Brining methods were probably used in the beginning, and they do not require caustic soda, but lye processing has been used since Roman times.

Since the ancient Romans couldn’t pop down to the shops to grab some caustic soda, I was curious about where they obtained the chemicals needed for lye curing of olives. The answer didn’t turn out to be very exciting. Turns out, lye was made from soaking wood ash, which produces potassium lye (KOH), rather than sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

🍏 🍏 🍏

🍏 For more on Olive processing, see:

http://www.madehow.com/Volume-5/Olives.html

https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8267.pdf 🍏

Pesticide Residues In Organic Food: A Food Fraud Indicator?

Each year I review the results of the pesticide testing program of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). I’m interested in how many organic products contain high levels of non-organic-approved pesticides because this can indicate food fraud.

High levels of pesticides on organic food could indicate that a person has labelled conventionally grown produce as ‘organic’ to make more money when it is sold. Organic food fraud is considered to be one of the most common types (I have no source to quote for this, apologies… different datasets give different estimates).

In 2019, my analysis showed that 26 percent of the ‘organic’ labelled foods tested by the USDA contained pesticides. Mostly these were NOT organic-approved pesticides. Just under half of those samples had pesticides present at unsafe* levels. A few samples even contained multiple different non-organic-approved pesticides at unsafe levels.

That means about one-quarter of the organic samples were potentially affected by food fraud.

Sadly, these proportions were higher than for 2014, five years previously.

The information I used to find these statistics was buried deep in the humungous pile of data collected by the USDA and made available for public download. Their pesticide residue program tests thousands of samples of dozens of food types from across the USA every year. Every sample is tested for around 200 different chemicals, including both “allowed” and “not allowed” pesticides and also for persistent environmental contaminants like DDT.

With the 2019 program having almost 10,000 samples of 21 types of foods that’s quite a robust data set.

What does the USDA think about pesticide residues in organic foods?

It’s notable that the USDA has never included a specific discussion of organic foods in its pesticide reports. Their program is not targeted at organic foods. Organic samples make up only a small percentage of all the foods surveyed. For example, only 9 % of samples in the 2019 program were organic.

To get the organic results, you have to download the raw data and interrogate it to see which, if any, organic-labelled samples contained residues that didn’t reflect their supposed organic status.

As I said earlier, last year’s results, which were for samples taken in 2019, showed that 26 percent of 845 organic-labelled samples contained detectable levels of pesticides. However, the residue tests used in the USDA’s program can detect tiny quantities of pesticide chemicals. They could be present in organic foods due to accidental contamination, environmental sources - perhaps drift from a neighbouring field - or from cross-contamination during packing and transport.

It’s the organic-labelled foods with high quantities of non-organic-approved pesticides that should be of concern to the USDA, who are responsible for enforcing organic regulations in the United States.

So what did the USDA say about the 9 percent of organic-labelled samples with unsafe* levels of non-organic-approved pesticides in their report last year? Nada! Nothing, not a word. They did not even mention the results for organic foods in their report.

What about this year’s results?

Last year’s report didn’t mention any problematic organic results - disappointing! - but this year’s data doesn’t even include them!

The most recent set of results, published last month, were for samples collected in 2020. I approached the data eagerly, hoping for an improvement in the results, because awareness of organic fraud has been growing amid widespread criticism of the USDA’s management of the organic food program. I was hoping that this awareness would have a positive impact on the results.

So I couldn’t believe my eyes when I downloaded the raw data and discovered that this year it is organised in such a way that you cannot link a specific pesticide test result to an individual sample for organic-labelled foods. You can see the number of detections but there is no way to know if those are from one sample or multiple samples.

This muddies the water for food fraud analysis and prevents me from comparing the 2020 results to those from previous years. An overview of the number of detections versus the number of organic samples shows a similar proportion to previous datasets, so the results are perhaps, unfortunately, similar to previous years.

And I’m afraid that’s all I have for you from this recent data set.

* the correct terminology is ‘tolerance’ which is the maximum amount of a pesticide allowed to remain in or on a food, set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Sources

🍏 Get the USDA Reports here and the datasets here. 🍏

News and Resources Round-up

No algorithm, just dedication… below is a carefully handcrafted selection from around the globe.

Our news and resources section is expertly curated (by me! 😎) and free from filler, fluff and promotional junk. Click the preview box below to access it.

This week’s news includes warnings about CBD edibles, monkeypox in food and Salmonella in sesame products.

Just for Fun

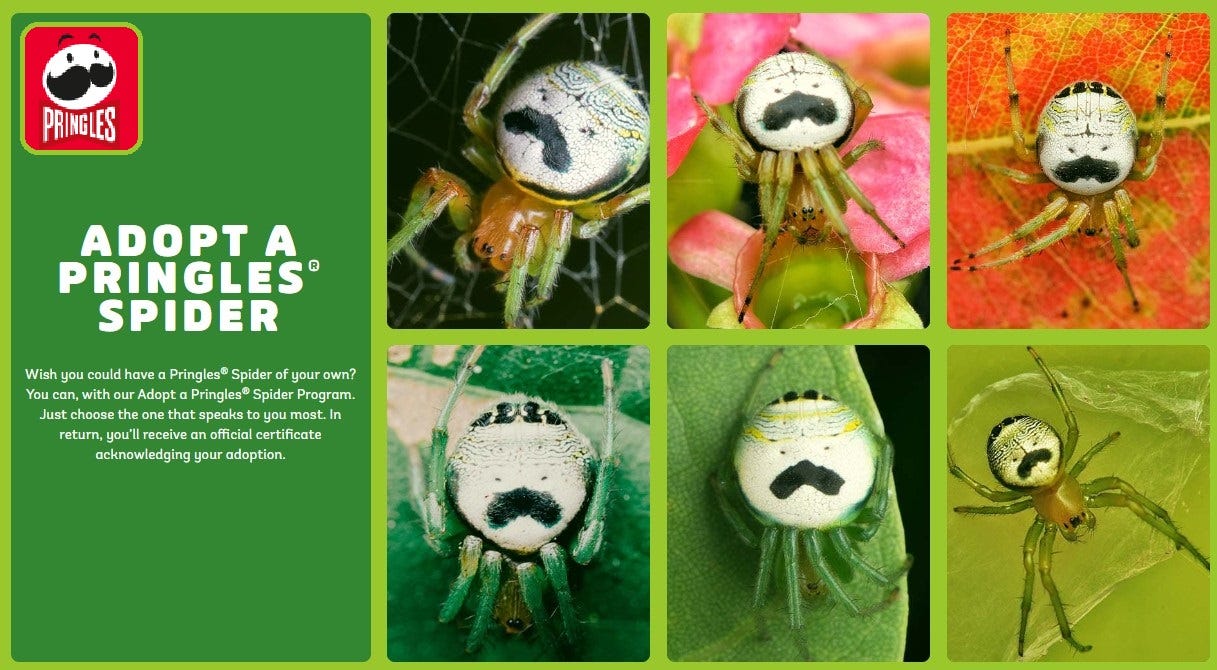

Adopt a Pringles Spider

This looks like a frivolous genetic experiment, which is a bit alarming. But there’s no need to be alarmed, it’s all-natural.

Some bright spark noticed a spider that looks like the moustachioed mascot on Pringle’s packs. And the brand owner, Kellogg, jumped right on it (figuratively speaking 😉)

Now you can adopt a Pringles spider, which is more properly known as Araneus mitificus. ‘Cause you know you want to!

Source: https://www.pringles.com/us/pringles-spider.html

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud incident reports, horizon scanning updates, plus audio.

Food Fraud News

Tainted fruit juice deception

A woman and her company have been charged with making and distributing grape and apple juice tainted with potentially harmful levels of