Bystander interventions and food safety culture

Learn how to empower workers to speak up if they see something wrong

Bystander intervention is a topic usually associated with bullying, harassment, racism or violence. However, it also has a role in preventing food safety failures.

When we see something that doesn’t look right, we start by asking:

1) Should someone intervene here?

2) Am I that person?

How we answer those questions determines whether we end up with a positive outcome or an escalating disaster.

Let’s consider bystander intervention in a food safety scenario.

Scenario

During the evening cleaning shift at a sandwich preparation facility, Ravi, a cleaner, notices that his coworker Lisa somehow has the wrong chemical coming out of her foamer.

What does Ravi do? (choose your own adventure)

Option 1: Ravi is worried but chooses to do nothing; he doesn’t want to embarrass Lisa or slow down the cleaning process.

Option 2: Ravi is worried but doesn’t want to say anything to Lisa, after all, she’s been working here for years, and he’s still new to the company. However, he decides something should be done, so he puts down his tools and goes to find the shift supervisor.

Option 3: Ravi goes straight to Lisa and tells her what he’s noticed.

What happens next?

Outcome for option 1: Ravi has said nothing. The cleaning shift finishes and the food contact surfaces aren’t properly clean, posing a food safety risk.

Outcome for option 2: Ravi spends 15 minutes trying to find the supervisor, who is busy on the phone outside. Lisa finishes her task and goes home, leaving the surface improperly cleaned and posing a food safety risk.

Outcome for option 3: Ravi tells Lisa what he noticed. She says she’s been feeling tired and wasn’t concentrating properly, and thanks him for pointing out the mistake before she had wasted too much time using the wrong chemical. She corrects the error and finishes the task, leaving all surfaces properly clean.

Interventions for hazard prevention

The scenario I just described is overly simplistic, but it makes a clear point: bystander interventions are a powerful way to stop problematic behaviour that poses food safety risks.

When I started work in food safety decades ago, the adage “If you see something, say something” was drilled into me by my mentors and manager.

But bystander interventions are complicated. Not everyone wants to say something when they see something. Power dynamics, fear of causing offence, lack of confidence and worry about being seen as a trouble-maker can all stop people from speaking up when they see something that is not right.

We can’t assume people will speak up if it doesn’t feel right in the moment.

I was reminded that a culture that encourages bystander intervention can be actively created during a recent training exercise with the Rural Fire Service (RFS) where I volunteer. One of the key foundations of RFS bush fire training is ensuring everyone will speak up if they see something that is dangerous or not right.

In the RFS, spotting hazards and communicating them to your teammates is part of the job, whether or not you think others have seen the hazard themselves. It’s a practice that undoubtedly saves dozens of lives on the fireground every year.

But the culture of “see something, say something” extends beyond the fireground and into the incident management teams of the RFS, too.

Mistakes made in the RFS radio room can be just as dangerous as mistakes on the fireground, costing precious time in an emergency, sending resources to the wrong location or providing ambiguous instructions to firefighters.

When I’m in the radio room, I not only expect my crewmates to tell me if I’ve made a mistake, but I am relieved if they do. It’s good to know everyone in the team is actively watching for communication errors, which are easy to make when a situation is heating up (literally!).

The culture in the organisation makes it easy for anyone to speak up without fear of ridicule, and easy for the person who's made a mistake to admit it without shame or fear of retribution.

Away from bushfires, a culture of “see something, say something” can prevent disaster on the sea as well. My boat-sailing friend tells every person who boards his vessel, “Watch out for hazards. Don’t assume I’ve seen something when I’m at the helm. If you see another boat, buoy or obstacle in our path, you must speak up. I’ll never make you feel silly for telling me about something that seems obvious. I want to hear if you see something. And don’t leave it too late: I want you to tell me straight away”.

A culture where it feels good and right to speak up loudly and often in the face of danger or miscommunication is good, but it’s not the norm.

In fact, prompt and suitable bystander interventions are relatively uncommon in public places, with typical response rates of less than 50 percent.

For example, a Japanese study of airway obstruction events for patients who ended up in hospital emergency departments found that witnesses only intervened half the time, despite airway obstruction being life-threatening and interventions significantly improving outcomes.

What encourages bystanders to take action?

In the context of sexual violence, research shows bystanders are significantly more likely to intervene if they believe their peers support such behaviour.

So it follows that if you can encourage a culture where it’s not just okay to intervene when a problem occurs, but actively encouraged, people will be more likely to act.

Perhaps just as importantly is how the intervention is received. Responses like “What would you know, you’re only new!” or “Of course I saw that burning branch was about to fall, I’m not an idiot” can stifle future actions.

It’s about team members….

Getting comfortable with “saying something”; and

Getting comfortable with receiving feedback.

Role-playing exercises and team training exercises with built-in intervention opportunities can help build these soft skills.

Other factors that affect whether bystanders will intervene include the number of other witnesses, with fewer witnesses increasing the likelihood of a response; the perceived severity of the problem being witnessed and the level of knowledge of the bystander.

Designated roles and responsibilities affect the likelihood of interventions too. For example, bystanders with a work role are significantly more likely to intervene in violent events than casual bystanders.

Scientists who study bystander intervention report that when there are a lot of people witnessing a problem, individuals are much less likely to take action compared to situations with fewer bystanders.

In a restaurant, whether or not patrons decide to respond to unsanitary food handler behaviour depends on the severity of the behaviour and their belief that an intervention will be effective (source).

The good news is that training in bystander intervention is very effective.

Tips for training

To improve bystander intervention behaviours in food safety scenarios deploy the following types of training:

Training that increases knowledge, so workers feel confident that what they are seeing is definitely a problem and not ‘business as usual’.

Food safety training that describes outcomes for consumers. This can increase workers’ understanding of the severity of a problem, with higher severity problems more likely to provoke a bystander intervention.

Role playing in teams, with a chance to practice intervening and receiving feedback.

Learning together in teams, where trainees are encouraged to correct each other. Small groups of less than 20 are recommended to allow for successful discussions (source).

Teach the five steps for successful bystander interventions, as described below.

Skills for bystander interventions need to be refreshed, with research showing that intent to intervene declines in the months after successful training (source).

Additionally, since it should be everyone’s role to say something if they see something, consider including this in job descriptions and required skill sets.

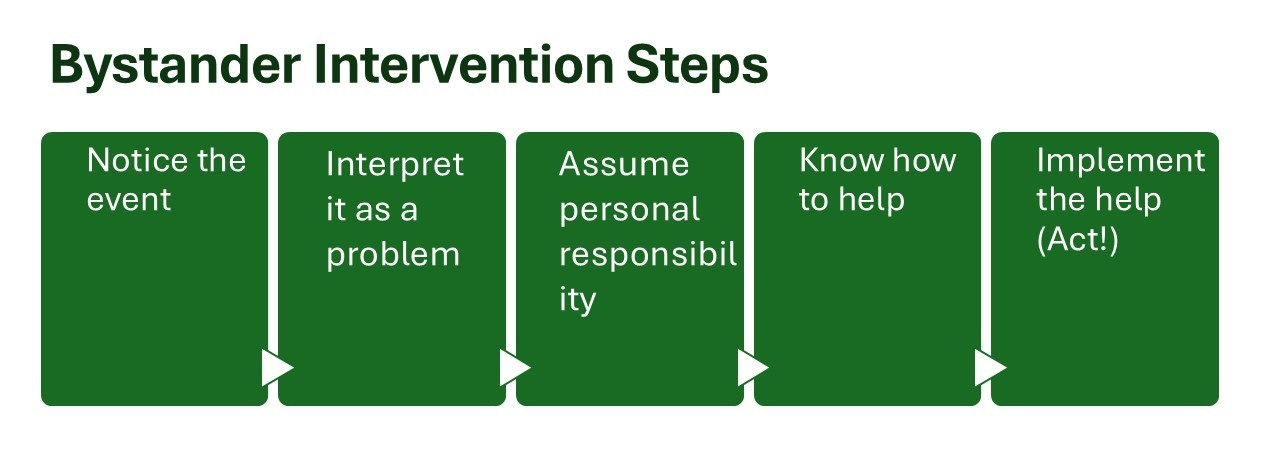

The 5 steps of bystander intervention

Five stages must occur for a bystander to successfully intervene when they witness a problem and these are described below. They are adapted from guidance published by Lehigh University, and are applicable to all potentially harmful situations, including violence, workplace bullying and worker safety as well as food safety.

1. Notice the Event: Other people in the area may be too busy to notice, while some may choose not to notice. Pay attention to what is going on around you.

2. Interpret It as a Problem: Sometimes it is hard to tell if what’s occurring really is a problem. If you’re unsure, err on the side of caution and investigate. Don’t be sidetracked by ambiguity, conformity or peer pressure.

3. Assume Personal Responsibility: If not you, then who? Do not assume someone else will do something. Have the courage and confidence to be the first.

4. Know How to Help: Never put yourself in harm’s way, but do SOMETHING. Help can be direct or indirect.

5. Implement the Help: Act.

In short: 🍏 A positive food safety culture actively supports the adage “If you see something, say something” 🍏 This concept, which encourages witnesses to speak up if they see something that is not right, needs to be explicitly taught and practised for the best outcomes, with frequent reinforcement 🍏

Further reading:

This article originally appeared in Issue 189 of The Rotten Apple.