176 | Surprising Fraud in a Cheap Food | Planning for Crises |

Plus, more on the South African poisonings

This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

Crisis management in the food industry;

Rice fraud - more common than you might imagine think;

Food Safety News and Resources;

Follow-up: South Africa poisonings;

Spicy food eaten fast (just for fun);

Food fraud news, emerging issues and recent incidents.

Hi lovely readers,

Thank you to everyone who signed up last week, welcome to our global food safety community, and a big shoutout to 👏👏 Chase 👏👏 for becoming a paying subscriber - I couldn’t do this without readers like you.

Welcome to Issue 176 of The Rotten Apple. I recently moved house and now live on a tsunami-vulnerable strip of low-lying coast. Have I done any crisis planning? You betcha: my tsunami plan is ready - hopefully never to be used.

Crisis planning is the first article this week - and yes, tsunami planning is needed if your food business is in a coastal area. Also this week, I explore food fraud in rice, which is popping up more and more frequently in my weekly searches of international media.

Plus there’s an update from South Africa on the spate of child poisonings - not good news I’m afraid - and an absolutely jam-packed food fraud news section for paying subscribers.

Wishing you all a crisis-free week.

Karen

Note: Subscription fees for new subscribers increase on 28th February for the first time in 3 years. Current subscribers are unaffected and retain access to the current price ($10 per month or $100 per year). Free subscribers should upgrade to a paid subscription now to lock in the existing price while it’s still available.

Crisis Management in the Food Industry

Crises come in many different forms, from recalls that cause reputational damage but little harm to consumers, to natural disasters and significant outbreaks. What they have in common is the potential to cause significant harm to health, reputation, or business operations.

Crises require immediate response and action to mitigate damage.

Recent crises

In February 2025, Coca-Cola in the United Kingdom and Europe had to recall canned beverages because they were contaminated with chlorate, possibly due to carry-over from a sanitisation process in manufacturing.

Regulatory authorities including the United Kingdom Food Standards Agency got involved, working with Coca-Cola to investigate the issue and make sure that the community remains safe. The recall received extensive coverage in the mainstream media and on social media, causing potential reputational harm but with a low risk of harm to consumers.

In September 2024, Hurricane Helene disrupted multiple poultry operations in the southeastern United States and damaged beer breweries in North Carolina. Production was disrupted by raw material shortages and supply chain interruptions. This natural disaster impacted businesses’ ability to operate and posed serious financial risks as well as risks to employees.

In July 2024, the US ready-to-eat meat producer Boar’s Head recalled around 208,000 pounds of liverwurst and other deli meat products due to possible contamination with Listeria monocytogenes. The recall was soon expanded to more than 7 million pounds of ready-to-eat products. Ten people died in the associated listeriosis outbreak. The crisis resulted in the permanent closure of the production facility and serious reputational damage to the brand.

Crisis management: prevention is better than cure

The best way to handle a crisis is of course, to prevent it in the first place. In fact, that is what the practice of food safety is all about.

However, as we’ve seen from the examples above, not all crises are the result of a failure in food safety protocols, and not all disasters are preventable.

When prevention fails

When an incident becomes a crisis, there are two ways a food business can respond:

Take an unstructured approach (make it up as you go along) or

Follow a crisis management procedure that has been tested and refined.

Which would you prefer?

A crisis management procedure describes how an organisation will respond to events that could disrupt operations, harm its reputation, or impact financial stability. Its main goal is to minimise damage, protect stakeholders, and quickly restore normal operations.

To create a crisis management procedure, a food business must first map out the sorts of incidents that could become a crisis, such as accidental contamination of food, malicious tampering with food, or a food fraud incident. Beyond food, incidents such as worker injury, natural disasters and acts of aggression should also be addressed in crisis management procedures.

For each scenario, ensure there are preventive controls in place to prevent the scenario or mitigate its impacts. Systems like HACCP, VACCP and TACCP are designed to prevent food-related incidents from becoming crises, while worker health systems, disaster preparedness and cybersecurity systems are designed to mitigate the risks from other incidents.

Early warning systems are an important element in crisis prevention by providing a food business with time to act on an incident before it becomes a crisis.

For example, a system for logging customer complaints that captures complaints from different sources, such as social media, phone calls and contact forms, can provide an early warning of a problem with a batch of food. An earning warning allows for a faster response, limiting the risk to other consumers and potentially reducing the amount of damage to the brand in a food safety incident.

Early warning systems can also be used to detect disgruntled employees, who pose a threat to other employees and food safety.

Environmental monitoring programs for detecting trends in pathogens and indicator organisms are another early warning system, providing advanced warnings of increased microbial contamination risks.

Steps to develop a crisis management procedure

The most important things a food business needs to survive a potential crisis are (1) effective prevention systems and (2) a procedure to follow when preventive actions fail.

When everything goes wrong at once, a formal procedure allows everyone in the business to keep calm and take action without having to make too many decisions in a high-pressure situation.

A company with a procedure will be subject to less stress and fewer negative impacts in a crisis compared to one without.

The procedure should include general processes to be followed in all crises and specific processes for each identified crisis scenario.

Step 1

Appoint a crisis response team. This team will identify potential crises, assess necessary resources, and create an overall response process for all crises.

There can be multiple response teams at various levels of an organisation, for example, one for each site and one for company headquarters in large companies.

Crisis response teams should include senior leaders at the relevant levels, for example, site management at the site level and C-suite leaders at headquarters. Representatives from every department of the organisation, such as production, logistics, human resources, IT and technical should be included on the team.

Crisis response teams should be supplemented by external experts such as crisis specialists, lawyers, food safety consultants, medical advisors, and PR or communications experts. These can be called on in the event of a crisis, and provide support to the response team.

Step 2

Each member of the response team should form a task force within their own department. The task force is made up of people who perform pre-planned actions during a relevant crisis.

For example, in a crisis involving an aggressive worker, the human resources task force will go into action. In a food safety crisis, the food safety task force will take action.

Step 3

Each task force writes its own procedure using a common framework.

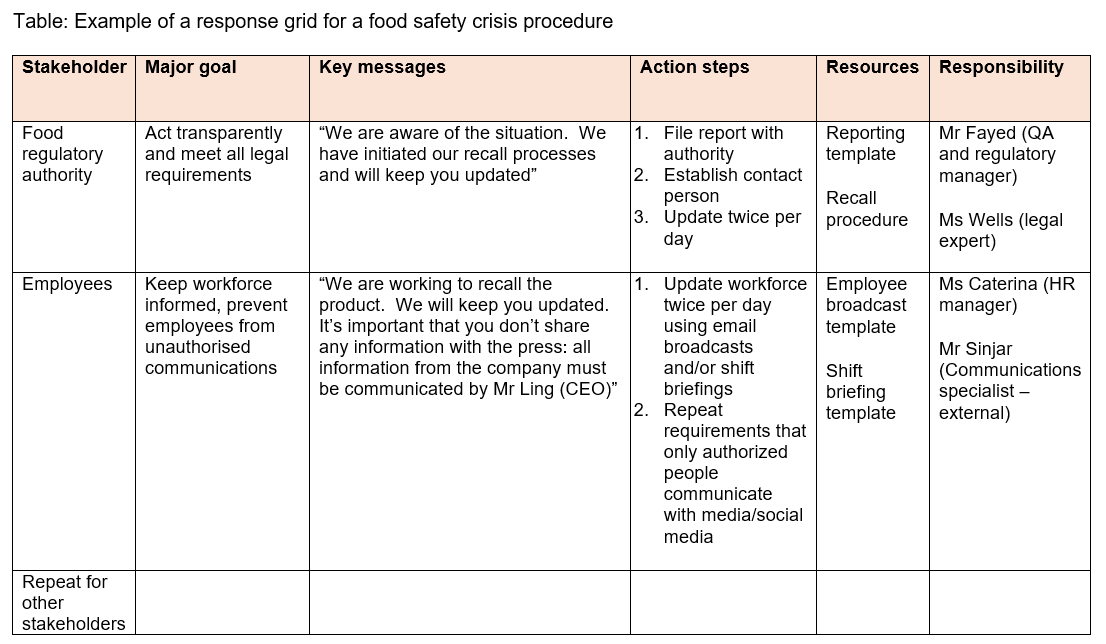

One way to write a procedure for each identified crisis is through the use of a response grid. In this method, the grid contains a list of every stakeholder impacted by the crisis, such as customers, consumers, shareholders, employees, and regulatory authorities, and outlines what action steps will be taken and who is responsible.

The crisis management procedure should include:

pre-appointed ‘documenters’ who will monitor the crisis and record details of actions taken throughout the response. These people should not be otherwise involved in the crisis response, with monitoring their only role. The information they record is used to analyse the crisis afterwards.

A post-incident review to identify what went well and what didn’t. Include corrective and preventive action processes to identify failures and initiate action to stop them reoccurring.

Timeframes and protocols for practising the procedure (“emergency drills”).

Crisis Management Plans for Food Businesses (a special supplement for paying subscribers of The Rotten Apple), describes crisis management plan creation in more detail and includes a downloadable checklist.

Practice is crucial

Emergency procedures are not used regularly so practising imagined scenarios is crucial to successfully surviving a crisis and developing robust procedures.

The following suggestions for practising crisis procedures are from Dr David Rosenblatt of Merieux NutriSciences, a veteran of many food safety emergency response drills.

Advice for effective crisis drills

1. Appoint a person with the authority to initiate an “emergency” scenario without pre-warning the rest of the organisation, so that the drill is a genuine surprise.

2. When the exercise begins make sure everyone understands it is a drill and not a real incident.

3. Include drills with multidisciplinary responses. For example, practice an earthquake scenario in which there is a food safety element, due to a contaminated water supply, as well as injured workers and damaged buildings.

4. Ensure that the monitoring persons keep an action logbook. This can include video documentation. It will be used to analyse the results.

5. Make the drill as realistic as possible.

6. Practice all the things you would do in a real crisis, such as press releases, regulatory reporting, employee updates, and calls to customers and distributors.

7. Conduct a post-event meeting to identify failures and opportunities for improvement, following the corrective actions and root cause analyses set out in the crisis management procedure.

Tips for surviving a crisis

Always tell the truth. Consumers and customers will be forgiving of food safety crises if the company tells the truth and apologises. Companies that try to obscure the truth or make excuses suffer more brand and reputational damage from a crisis than those that are transparent.

Have a pre-chosen location for your crisis response centre: a training room or meeting room with communications equipment, whiteboards and refreshments.

Schedule update meetings at the same times every day where response team members can come together and share information. The information can then be conveyed to other stakeholders such as key customers.

Takeaways for food professionals

Crises are easier to survive if your company has a written crisis management procedure, which reduces decision-making during times of stress and ensures no important steps are forgotten.

Crisis management plan development is a multi-disciplinary task requiring input from all parts of the organisation.

For successful crisis management, practice is critical.

Resources

Crisis Emergency Handbook for Food Managers | The Twin Cities Metro Advanced Practice Center

Step-by-step guidance for maintaining food safety in 10 different emergency situations, in English and Spanish

Webinar (on-demand): Crisis management in the food industry: prevention, mitigation and investigation Dr David Rosenblatt, hosted by IFSQN

Sources:

Safety Culture (2024) Crisis Management Plans. Available from https://safetyculture.com/checklists/crisis-management-plan/

Rosenblatt, D. (2024) Crisis management in the food industry: prevention, mitigation and investigation (Webinar) Available from: https://www.ifsqn.com/food_safety_videos.html/_/ifsqn-videos/food-safety-fridays/crisis-management-in-the-food-industry

Quality Assurance Mag (2025) Surviving the Next Big Disaster. Available from: https://www.qualityassurancemag.com/article/surviving-the-next-big-hurricane-natural-disaster/

International Standards Organization (2022) Crisis management guidelines ISO 22361:2022. Available from https://www.iso.org/standard/50267.html

Rice fraud

Fraud in rice is more common than you might imagine

Every time I update my food fraud database there are entries to be added for rice. Every time.

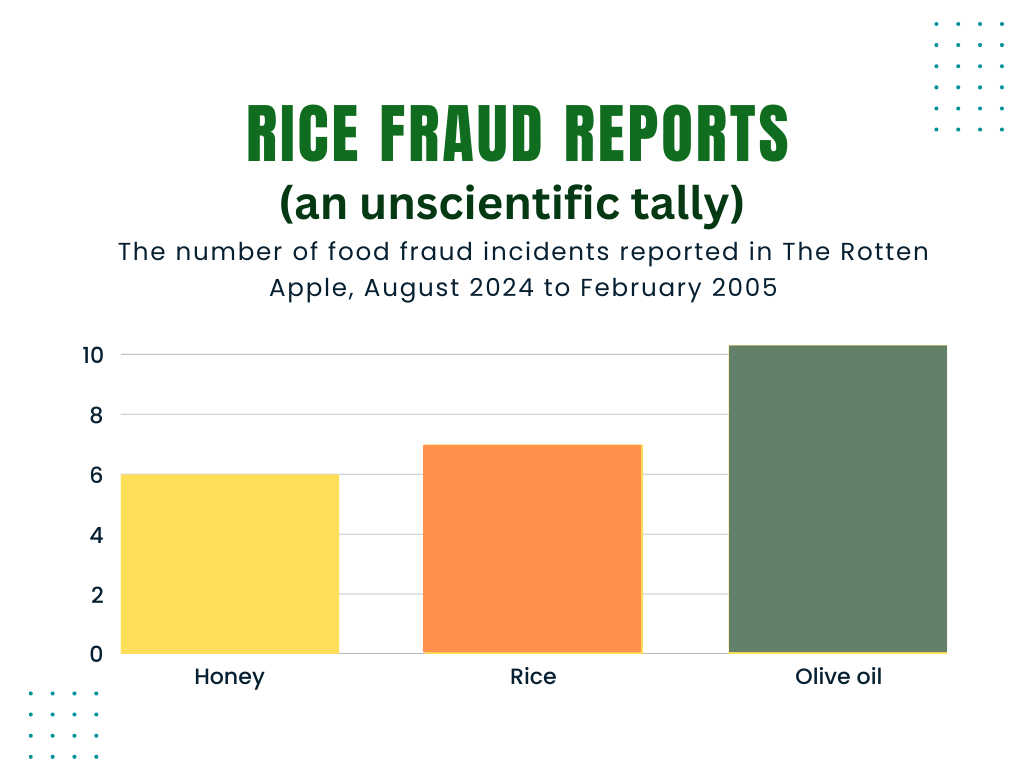

It’s surprising because we usually think of food fraud as a phenomenon that affects expensive food products like honey, olive oil or wine. However, in the past six months, I’ve reported on more rice-related food fraud incidents than almost all other food types, even honey.

So what’s going on with rice?

Rice got more expensive in 2022. In June of that year, I noted that The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) rice price index had risen for the fifth successive month with experts warning rice is “the commodity to watch” in terms of global food prices.

One year later, in 2023, prices for all globally traded food commodities tracked by the FAO were falling, except for rice and sugar. Rice prices increased by 9.8 percent from July to August that year, to reach a 15 year high.

At around the same time, India implemented a ban on white rice exports over domestic food security concerns and the world’s second-largest rice exporter, Thailand, urged farmers to plant less rice to save water.

Rice was changing from an ultra-cheap staple food to a more expensive product. This was when I began to notice more reports of rice fraud in the international media.

Here are some of the ways rice fraud shows up:

Rice is frequently smuggled between countries where there is a price differential. For example, rice is subsidised by government programs in India, making it cheap compared to neighbouring countries.

Rice quality and grades are misrepresented, such as in these recent incidents in South Korea and Brazil:

In a crackdown on rice fraud, officials found ordinary grade rice had been misrepresented as top-grade rice; past seasons’ glutinous rice had been repacked and sold as current season rice; and rice varieties had been misrepresented. Thirty-three organisations were charged with crimes or fined – South Korea 26/12/2024

Rice (10,500 kg) in 5 kg packages has been seized from a supermarket chain after officials discovered the rice was of an inferior quality and grade to what was claimed on the packs – Brazil 06/11/2024

GMO rice is labelled organic, as reported in the August edition of the EU Agri-food Fraud Suspicions report.

Rice labelled basmati or jasmine is not of the declared variety.

Premium rice brands are mimicked by counterfeiters who repack rice - sometimes from illegitimate sources such as illegal imports - into bags labelled with premium brand names, such as in these incidents in Burkina Faso and Panama:

Rice (14 tons) which had been illegally repackaged into bags labelled with a different brand name was seized. The rice was of a lower-priced brand and the person repacking the rice was not the authorised brand owner of the new brand name used for repacked rice – Burkina Faso 16/08/2024

A shipment of rice from China, fraudulently labelled with the name of a premium local brand was the subject of a complaint by the brand owner to authorities. At least 15,000 quintals of rice are being smuggled into the country illegally each year – Panama 14/11/2024

There are frequent reports of corruption within the government rice program in India, with the government vowing to treat the smuggling of rice as organised crime in December 2024, when 640 tonnes of rice from a ration program was seized as it was allegedly being illegally exported on a foreign ship. This was just one of 13 cases of illegal export of rice from the same port in 6 months, with suspected links to corruption and organised crime and with the rice possibly destined for Africa.

There are also reports of illegal and problematic imports to countries including Nigeria, where 1,000 bags of smuggled rice were seized from smugglers on boats last week and Kenya, where thousands of tons of aflatoxin-contaminated rice imported from Pakistan somehow avoided proper inspection and was released into the market in 2024.

Smuggling, false claims about quality, varieties and organic status: these are the sorts of fraud you might expect in rice. But there have been other frauds that are much more surprising.

For example, three factories that allegedly produced fraudulent Thai jasmine rice were discovered in China in 2023. The rice was allegedly grown in China, was not Thai jasmine variety and was flavoured with undeclared and illegal artificial flavourings (pyrazine and pyrrole). It was misrepresented as Thai jasmine rice to consumers.

And then there is the plastic rice controversy, in which consumers across the globe complained that the rice grains they purchased were actually made of plastic. Although the plastic rice phenomenon was considered a viral social media myth and failed most fact-checks, a well-known British food fraud expert went on the record in 2022 claiming a food company told him they found 10% plastic rice in a consignment they had received.

Perhaps the most unusual rice-related food fraud incident I have heard recently was reported in the European Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) in December. Rice was withdrawn from the market in Germany and the Netherlands after it was found to contain Dye CI15585 (D&C Red No. 9) following a consumer complaint. The dye is not authorised for use as a food additive and is carcinogenic in animals.

Takeaways for food professionals

It’s tempting to imagine that lower-cost bulk commodities like rice are not vulnerable to food fraud, but that just isn’t true.

Any food that is traded in large quantities provides opportunities for criminals to profit by moving it across borders illegally, making false claims about it or by diluting it with lower grades of the same material.

As we’ve just heard, rice is affected by all these types of food fraud. Raw rice grains have also been affected by adulteration-type food fraud, with artificial flavours used to make fake jasmine rice and carcinogenic dye discovered in rice a recent food safety incident in Europe.

When purchasing rice, be aware of its vulnerabilities and be sure to implement mitigations to reduce your exposure to food fraud.

Food Safety News and Resources

My food safety news and resources are expertly curated from around the globe and free from ads, fluff and filler. This week’s scary news: thousands of tons of aflatoxin-contaminated rice are in the market in Kenya.

Click the preview below to read.

Follow up: More on the South African poisonings

In Issue 173 I reported on the scary poisonings that have killed dozens - perhaps hundreds - of people in South Africa, many of them children. To me, the poisonings seem mysterious, because they are linked to packaged snacks but are being blamed on pesticide contamination of food.

Manufactured food sold in sealed packages should not contain pesticides in quantities large enough to kill a person in a single meal, even if accidentally contaminated while in a store.

Last week, another child died, with her family providing a detailed description of what she ate, and how she died. As in other cases, she died soon after eating a packet of chips, with traces of the pesticide Terbufos found in her bloodstream. Alarmingly, her parents couldn’t explain how she had come to get the chips, which they had not given her.

If this one packet of chips was so lethal, what about the other packs in this batch, or from the same store? Was it only this one child who was poisoned, and if so, why? Or did other children also get sick, but recover?

As I said in Issue 173, even accounting for the difficult circumstances in South African townships, accidental contamination doesn’t seem a plausible explanation for so many deaths in such similar circumstances to me.

Meanwhile, the authorities continue to crack down on sellers of expired and unauthorised foods. Last week a farmer was arrested in Mpumalanga, accused of storing expired and rotten food including around 1,000 crates of meat, chicken and dairy products and in Mgcawu District Municipality, 4 tuckshops were raided by police, with 3 of them shut down. Liquor and expired food worth R 18,937 was confiscated and one tuckshop owner was fined.

Main source: Girl, 7, dies after eating chips contaminated with a deadly insecticide | Press Reader

« Thank you to Ellenor from South Africa for this news »

Spicy food eaten fast (just for fun)

If you’re up for something weird and want to watch Chinese men eating fast while wearing very strange outfits, this is for you. I’ve no idea what to make of this video but it is certainly a compelling watch, especially if you read the English subtitles 😮🤔.

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 Revised Food Fraud Resilience Self-Assessment Tool;

📌 Recalled oil relabelled and sent back to market;

📌 Saffron fraud case closed, ten years on;

📌 Essence and dyes seized from a suspect olive oil manufacturer, ostrich curry, bottles from garbage used to pack beverages and lots more…

Food Fraud Resilience Self-Assessment Tool - updated

The National Food Crime Unit of the United Kingdom has revised their Food Fraud Resilience Self-Assessment Tool. Here’s what I said about the earlier versions.

The tool is designed for food businesses to allow them to:

- Assess their resilience to fraud

- Gain awareness of the risks fraud poses

- Ask themselves the right questions to strengthen their resilience.

Food Fraud Resilience Self-assessment Tool | Food Standards Agency

Recent food fraud incidents

Ostrich curry sold at a takeaway restaurant was found to contain sheep meat instead of ostrich meat. The manager pleaded guilty to offences under the Food Safety Act and was fined and ordered to pay court costs and a victim surcharge. The business was also fined and ordered to pay costs and a victim surcharge – United Kingdom 07/02/2025

Source: https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/uk-world-news/indian-takeaway-fined-putting-sheep-9927993

Follow up: Olive oils from 12 brands that were tested on suspicion of adulteration by authorities in 2024 have been confirmed to be non-compliant

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Rotten Apple to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.