196 | Chocolate Fraud, Chocolate Safety, Chocolate Mysteries |

Celebrating the wonderful world of chocolate

Why is chocolate so good?

Chocolate and food safety

Chocolate supply chain challenges

Chocolate and food fraud

Food fraud news: recent incidents

Happy Chocolate Day to you!

This week’s post is 100% chocolate. I’ve tried to include something for everyone… a little bit of food science, some food safety, and (of course) food fraud vulnerabilities too.

But before we get to that, I want to say a huge thank you to everyone who has renewed their paid subscriptions this past week, with big shoutouts to 👏👏 Jess from Saputo, Neha and Graham from Australia, Fiona from Scotland, Chris from Tennessee and Lynn from Britain 👏👏.

Welcome to 👏👏 Cathy, Leah and FSQR 👏👏 for becoming paid subscribers and to Helen a Good Apple subscriber whose support provides scholarships for students and academics.

Thank you. I’m grateful to have your support in our community of food safety champions.

Have a great week,

Karen

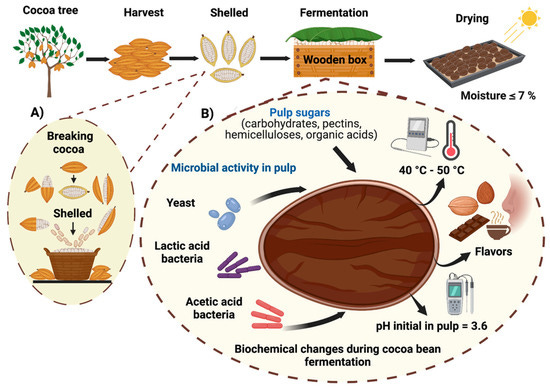

Cover image: Cocoa bean processing and fermentation from Gutierrez-Rios, et. al (2022)

Why is chocolate so good?

It’s World Chocolate Day.

We humans love chocolate (okay, most of us love chocolate*). It’s a food that is unique with respect to its sensory profile, psychoactive components and supply chain challenges. It is also affected by unique food safety and food fraud characteristics.

Let’s dive in.

Consumers love chocolate for its richness, smoothness and sweetness. But it’s not just the flavour and texture that draw us in. The first chocolate lovers, in Southern and Central America, consumed it in a form that was neither smooth nor sweet, but they were also crazy about it.

When it was catalouged by Western science, it was given a name that reflected its status and mythology, Theobroma cacao, meaning food of the gods (theo broma + cacao, the Indigenous Central American name for the cocoa seed)

The ancients prized it for its flavour, colour, and its psycho-active components theobromine, caffeine and phenylethylamine, deeming it an intoxicating beverage unsuitable for women and children.

Theobromine is a natural stimulant found in - and named after - chocolate. It acts on the central nervous system, providing a mild energy boost and can enhance cognitive function.

Caffeine is also present naturally in chocolate. It is also a stimulant, enhancing alertness, concentration and reaction times.

Phenylethylamine is known as the love chemical. It stimulates the release of endorphins and dopamine in the brain, enhancing mood and creating feelings of happiness and excitement.

So chocolate tastes great, enhances our mood and gives us energy and alertness. But that’s not the only reason we love it.

Chocolate also has a very unusual texture.

If you’ve ever munched on cheap compound ‘choc’, made without cocoa butter, you probably noticed it took a bit too long to chew and clear from the mouth. That unattractive goopy-fat-mouth-feel arises because alternative fats don’t melt as fast as cocoa butter.

Cocoa butter has a unique melting profile, which allows it to melt almost instantly at mouth temperature, while still remaining brittle and ‘snappable’ at room temperature.

Can you think of another food that can do that?

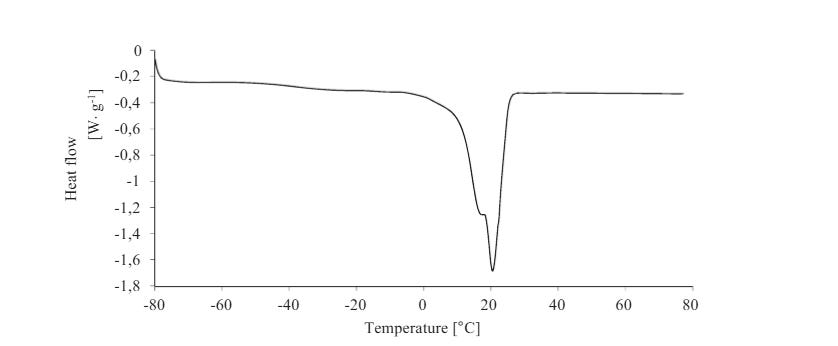

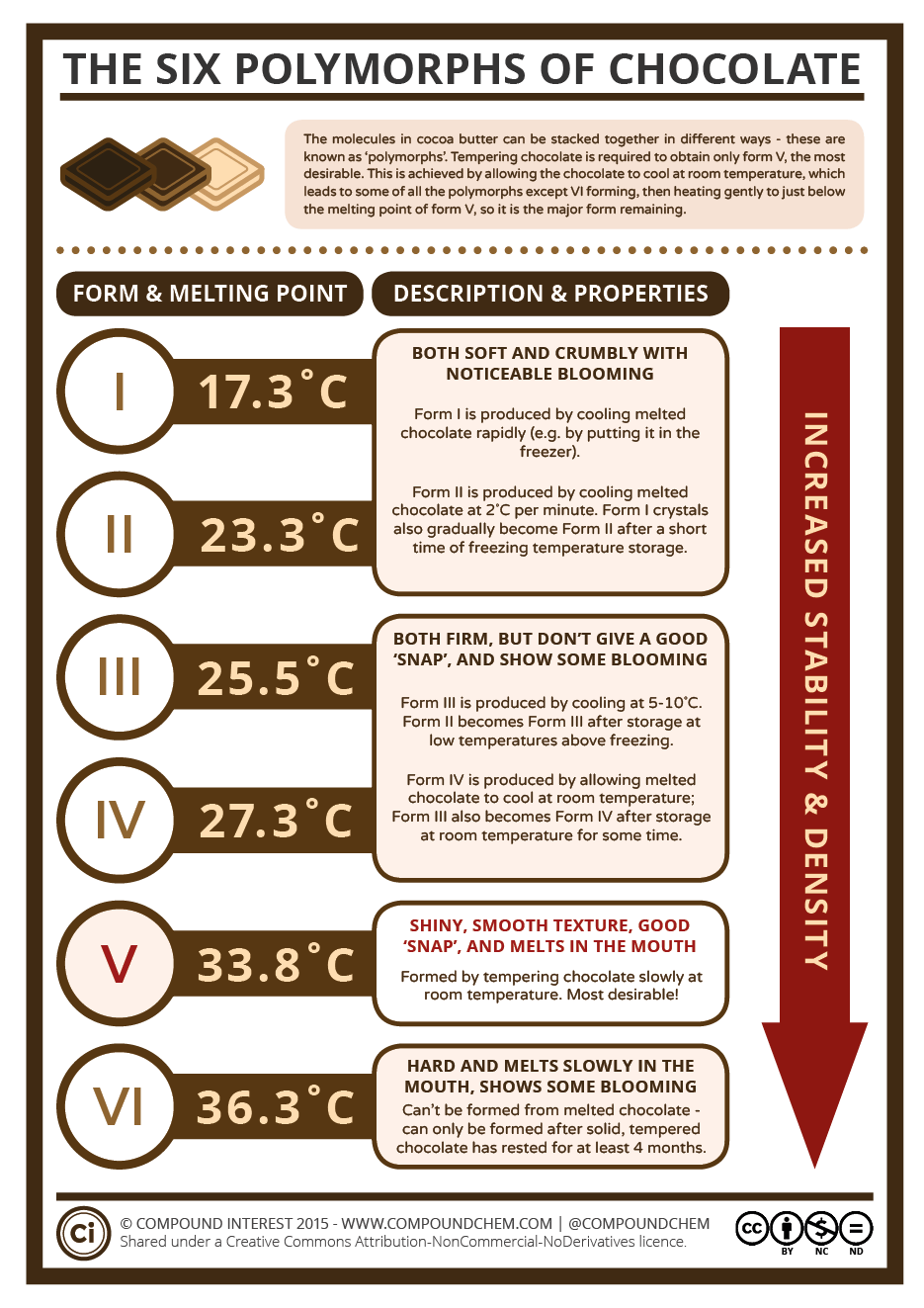

The special melting characteristics of chocolate are due in part to cocoa butter's polymorphism. The fat molecules can arrange themselves into crystals of different shapes, each with a distinct melting point and melting curve.

Tempering, a process that involves controlled heating and cooling of chocolate, causes the cocoa butter to crystallise into the desirable "form V" crystal, which results in high sheen, and a satisfying snap, as well as the ideal melt-in-the-mouth texture.

Other crystal forms of cocoa butter are less desirable. For example, forms I and II melt at lower temperatures (17oC and 23 oC respectively) and result in chocolate that is soft and crumbly with noticeable blooming.

Where does chocolate come from

The three top cocoa-bean-producing countries are Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Indonesia, which account for 43%, 12% and 11% of global production respectively.

Most cocoa bean producers are farmers with small plots of land, rather than large plantations.

The trees take 4 to 5 years to mature, can produce good yields for around 70 years, and live to around 200 years. Cocoa trees produce thousands of flowers every year but very few flowers produce pods. The flowers are pollinated by biting midges called Forcipomyia.

It takes around 1,200 seeds from 40 pods to make 1 kg of cocoa paste.

There are three main cultivar groups for chocolate production: Forastero, Criollo and Trinitario, with the rare and expensive Criollo said to be less bitter and more aromatic.

The cocoa tree originated in the Amazon basin, and was either domesticated there 5,300 years ago, or was domesticated in Central America 3,600 years ago, having been transported from the Amazon basin by traders.

One set of researchers, who used genomic analysis of 200 cocoa plants, assert that the people who domesticated the trees, which were of the Criollo cultivar group, selected for genes related to the production of anthocyanins, theobromine content, and disease resistance. However, in the process, the yield suffered, with the domesticated trees producing fewer fruit per season than their wild ancestors.

Forastero-group cultivars, including Amenolado and Arriba varieties, are more disease-resistant and easier to grow than other cultivar groups and account for 80% of commercial chocolate production.

Chocolate and food safety

Chocolate presents a range of challenges when it comes to food safety, partly because of its unique characteristics and partly because of its complicated production process and ingredients.

Pathogen survival

Salmonella and other pathogens can persist in chocolate during processing and in stored products for months due to the high-fat, low-moisture environment.

There have been multiple outbreaks of salmonellosis from chocolate and cocoa powder. In some of those outbreaks, Salmonella was never found in the finished product. Where it was found in products, it was often present at levels of less than 1 colony forming unit per gram of food.

Unfortunately, only a few Salmonellae cells are needed to cause illness, especially in children. In high-fat foods like peanut butter and chocolate, it’s thought that the fat protects the Salmonellae from stomach acid, allowing them to make it through to the victim’s intestines, where they can grow and cause infection.

(Sources: Mondelez International (2020) and MPI New Zealand (2010))

Aflatoxins in nut ingredients

Nuts are a common ingredient in filled and flavoured chocolate products. With aflatoxins - toxins produced by certain moulds - in nuts a growing food safety concern in many parts of the world due to increasing temperatures and humidity, chocolate makers now need to be wary of chemical hazards from aflatoxins.

Heavy metal contamination

Multiple surveys by a US consumer group have revealed worrying levels of lead and cadmium in a significant proportion of chocolate products in the USA.

Lead and cadmium get into chocolate via cocoa beans. Cadmium gets into cocoa beans before harvest, by plants taking cadmium from the soil into the beans, while lead primarily gets into cocoa beans during post-harvest processes such as fermenting and drying.

Get the full story (plus sources) here: Cadmium and Lead in Chocolate – How does it get in? What can be done? | The Rotten Apple Issue 112

Undeclared allergens

Undeclared allergens and allergen labelling errors still account for a significant proportion of recalls across many countries, including the United Kingdom and Australia.

Chocolate production often involves multiple opportunities for cross-contact with allergens, particularly peanuts and tree nuts, which are common ingredients in filled and flavoured chocolates and confectionery, and milk, making allergens a hazard of concern in chocolate.

Chocolate supply chain challenges

Chocolate’s supply chain is vulnerable to changes in weather, farming practices, and global trade networks. It is a truly global product, with the beans mostly grown in developing nations and processed into chocolate in wealthy nations.

Supply chain challenges include problems with cultivation, trade, sustainability, and compliance.

Threats to production

In recent years, the combined effects of extreme weather events, tree diseases and climate change in the world’s biggest cocoa-growing regions have severely impacted yields.

Cocoa farmers are reportedly abandoning their trees or choosing not to replace ageing trees as the crop becomes less profitable due to rising production costs and declining yields.

In Côte d’Ivoire, for example, prolonged droughts, unpredictable rainfall, and increased plant diseases like swollen shoot have made cocoa farming unprofitable for many, leading farmers to leave their plantations or switch to alternative crops.

In Ghana, the world’s second largest cocoa producer, gold mining is now impacting cocoa production and taking over fertile land once used for cocoa growing.

The Swiss media outlet Swissinfo reported in 2022 that cocoa farmers were selling their land to illegal gold miners, with swathes of farmland transformed into wastelands dotted with piles of clay contaminated with mercury, a by-product of gold extraction.

In the same year, a survey by the Ghanaian cocoa board revealed that 19,000 hectares of cocoa plantations had been lost, taken over or damaged by illegal gold mining.

With recent large increases in the price of gold and more problems with cocoa production due to disease and climate change, there is increasing recognition that more cocoa farmland will be lost to mining this year.

With production declining, cocoa prices are rising. They increased by 25% in the two years to 2024.

Prices have since stabilised somewhat, but cocoa futures today are still more than three times higher than they were in 2021 – 2023.

Read more

🍏 Chocolate Supply Chains in Crisis | The Rotten Apple Issue 129 🍏

🍏The surprising link between illegal gold mining and chocolate | The Rotten Apple Issue 180 🍏

Threats to trade and compliance

Chocolate has always been considered an at-risk product for unethical labour practices, particularly in West Africa, which supplies around 60 to 70% of the world’s cocoa. Structural poverty, low farm-gate prices, and lack of bargaining power among farmers create conditions where forced labor, debt bondage, and child trafficking can occur to meet demand and maintain profitability.

Estimates indicate that over 1.5 million children are involved in child labor on cocoa farms in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, with many engaged in hazardous work, and there have been documented cases of both child and adult workers being subjected to exploitative or slave-like conditions in other cocoa-producing countries as well.

In 2023, the commodities trader Cargill was ordered to pay more than $120,000 by a Brazilian court after prosecutors alleged it did not know the extent of child labour in its Brazilian cocoa supply chains because it purchases from hundreds of producers, co-operatives and merchants. Cargill denied the allegations.

In 2021, Hershey and the Rainforest Alliance were sued for false advertising in the US, with Hershey accused of turning a blind eye to child labour in their supply chain and the Rainforest Alliance accused of being unable to prevent or even account for it.

Certification schemes like Rainforest Alliance and FairTrade are supposed to give assurance of ethical work practices in the production of the certified foods, but their efficacy has been questioned.

Researchers who reviewed the ability of schemes like FairTrade to assure child-labour-free processes in 2018 were told by a certifier “We are working with around 11,800 cocoa farmers, so we have not been able to visit any farms as of now”. Instead, they relied on farmers’ cooperatives to verify the working standards at farms.

The cooperatives receive a premium for certified cocoa, compared to uncertified cocoa, so self-reporting about their farmers’ compliance with certification standards for labour practices is problematic.

In 2025, the bigger concern with compliance and sustainability in cocoa is related to the coming enforcement of the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Under these rules, due to be enforced from December 2025, cocoa and chocolate products imported into the EU must be proven to be deforestation-free, meaning the land used for cocoa production has not been deforested after 2020.

The importer must provide geolocation data, traceability to farm level, and comprehensive documentation at multiple points in the supply chain.

In West Africa, the major growing region, there are significant differences between the way beans are regulated and priced between the two largest producers, Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana.

Some cocoa farmers in Côte d’Ivoire sell their beans to traffickers who smuggle them out of the country to be resold in places such as Guinea and Liberia, where they can fetch a higher price than the government-mandated prices in their country. In 2024, 150,000 tonnes of Ivorian cocoa beans were said to have been illegally exported in this way.

Threats to forests

Last year, a media outlet in France reported that rules and checks implemented by the Côte d’Ivoire government and designed to prevent deforestation had resulted in cocoa farmers leaving the country and setting up plantations in neighbouring Liberia instead.

Liberia, they say, has “an almost total lack of monitoring”, making it attractive for farmers who grow beans on newly deforested land there, before moving the beans back into Cote d’Ivoire to avoid traceability checks. Tens of thousands of cocoa farmers have reportedly crossed the border already, threatening thousands of hectares of virgin forest.

Chocolate and food fraud

With supply chains both complicated and threatened by multiple supply-demand imbalances and uncertainties, it’s no surprise that cocoa is extremely vulnerable to food fraud, with cocoa beans claimed to be organic, fair trade and ethically or sustainably sourced the most at-risk for fraud.

Fraud in cocoa beans can take the form of theft, smuggling, misrepresentation of fairtrade/rainforest status, false organic claims or misrepresentation of geographical origin; as well as simpler frauds such as adding rocks or sticks to bags of beans to increase their weight.

The EUDR, which includes significant traceability requirements and penalties for cocoa beans from recently deforested land, creates significant pressure on cocoa bean producers and traders to falsify bean origin and traceability data to make beans appear to have originated in non-deforested or ‘low-risk’ designated areas.

There is significant smuggling of cocoa beans between West African countries, due to price differences between countries, and this confounds traceability attempts.

In addition to fraud in cocoa beans, manufactured chocolate also has food fraud challenges.

Counterfeit chocolate - chocolate products packaged to look like premium brands but made without the permission of the brand owner - is perhaps the most commonly reported type of fraud in chocolate.

A notorious example of counterfeit chocolate is ‘Wonka’ bars, which periodically resurface in the United Kingdom. The Wonka brand is owned by Ferrero, which hasn’t sold Wonka chocolate bars in the United Kingdom for years.

The fake bars are produced or repackaged by unregistered businesses or individuals with no regard for hygiene or labeling regulations, making them potentially unsafe to eat, particularly for people with food allergies due to undeclared allergens. Incidents have included unhygienic manufacturing conditions, incorrect or missing ingredient lists, and the use of fake business addresses on packaging

Other frauds that have been unmasked include an ‘artisan’ producer in Italy who was allegedly buying industrially produced Easter chocolates, discarding the wrapping and then reselling them as ‘own production’ (i.e., artisanal); and smuggling operations.

In January 2025, a woman was caught in Germany with 460 bars of chocolate concealed in her luggage after an international flight. Customs officials suspect the chocolate bars were being imported for commercial sale, because of the large number of bars and because chocolate of that type had been made popular on TikTok, with each bar fetching around 25 euros.

The bars had no ingredient or allergen information on their packs, posing a health risk to consumers. If successful, the smuggling would have resulted in the woman evading more than 330 euros of import duties.

In February 2025, authorities in Europe discovered chocolate from the United Arab Emirates and Turkiye made with hydrogenated palm oil instead of cocoa fat, containing undeclared colourants and with a higher fat content than declared.

It’s likely these frauds are just the tip of the iceberg. I estimate there are many instances of inauthentic claims made about artisanal and boutique chocolate products in wealthy countries. ‘Single origin’ chocolate, organic chocolate and fair trade chocolate products are moderately likely to be affected by inaccurate claims due to problems in their supply chains or intentional deception by the brand owner.

Chocolate fun facts

Did you know….

Consumers in different countries have radically different ideas about what makes chocolate ‘good’. Americans like their chocolate light, sweet and milky, while French people prefer their chocolate dark and bitter. The Swiss and Japanese like chocolate that is buttery, satiny and very smooth.

The pulp that surrounds fresh cocoa beans can be fermented to an alcoholic beverage and is eaten as a snack. One (unverified) source claims the Aztecs mixed the ground beans with tobacco for smoking.

The early American civilisations who consumed cocoa as a bitter beverage prized it for its psychoactive compounds theobromine, caffeine and phenylethylamine, selectively breeding cocoa trees for higher theobromine production.

Despite hundreds of years of scientific research, there is still uncertainty about the details of cocoa bean fermentation. The fermentation traditionally happens on-farm and is spontaneous, performed without the use of starter cultures.

Researchers disagree about the role played by fermentation in the sensory characteristics of the finished chocolate, with some saying that the fermentation has a major impact on taste and others saying different microbial populations during fermentation create few differences in the end product, with tree variety, geography, drying, and roasting processes more important.

The fermentation, which takes 7 days, is a complex succession of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria. They produce compounds including ethanol, lactic acid and acetic acid, and create temperatures of up to 50oC giving rise to flavour precursors that are further developed during drying and roasting.

Conching, the process used to make chocolate smoother and more aromatic, was invented by Rodolphe Lindt (yes, that Lindt) in Switzerland in 1879. It is called ‘conching’ because Lindt's original machine resembled a conche, the French word for shell. The process involved continuously mixing and aerating chocolate in Lindt’s shell-shaped vessel.

The largest chocolate bar ever made weighed 4.4 tons, earning a spot in the Guinness Book of Records.

The most expensive chocolate bar ever sold was 100 years old when it was auctioned as part of a collection of items from Captain Robert Scott's expedition to the Antarctic (1901–1904). The bar was still in its wrapper inside a cigarette tin, and sold for £470.

American chocolate tastes different to European and British chocolate because of a secret process pioneered by Milton S Hershey (yes, that Hershey).

The process was developed to stabilise milk for chocolate production in the 1930s when refrigerated transport was not widely available. It is said to be similar to a ‘controlled deterioration’ or souring of milk.

The process creates butyric acid, which has a sour, cheesy taste and is responsible for the ‘vomity’ smell in parmesan cheese. And vomit. Other American chocolate makers, who don’t use the Hershey process, add butyric acid to please US consumers.

When the Spanish first arrived in Central America, a chronicler who travelled with the conquistador, Hernán Cortés reported that the Aztec leader Motecuhzoma (Montezuma) drank fifty flagons of cocoa beverage per day. The beverage was made by whisking ground cacao beans with hot water and sometimes seasoned with vanilla or chilli pepper.

Sources:

All sources are provided directly within the text as hyperlinks.

*An entire block of dark chocolate with roasted hazelnuts was harmed during the making of this post.

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 Method for floral honey discrimination;

📌 Durum wheat warning;

📌 Expired bakery products;

📌 Five ministers resign over EU farm fraud