Consumer-derived outbreak data - a new tool in the toolbox

Downloadable e-book: Issues 176 to 200

Rare: a food fraud recall

Food Safety News and Resources

Radioactive shrimp unpacked

Food fraud news: undercover honey investigation + methanol in paprika explained

Hi, Happy Monday!

The question I'm asked most often about The Rotten Apple is "How do you find things to write about every week?" Honestly, it’s easy to find subjects: there’s always something fascinating to explore in the world of food.

This week, the challenge is not "What shall I write about?" but "What do I need to leave out?" There were so many things I wanted to talk about. I settled on radioactive shrimp, undercover honey investigators and a recall response to food fraud - surprisingly, recalls like this don’t happen very often.

Enjoy,

Karen

P.S. Big shoutout to 👏👏 Alondra from the soup company 👏👏 for upgrading to a paid subscription and 👏👏 Marisa, Ads, Leanne, Gerhard and Vicki 👏👏 for renewing. Every subscription makes a difference, thank you!

Cover image: Freepik

A new tool to reduce the size of outbreaks and recalls

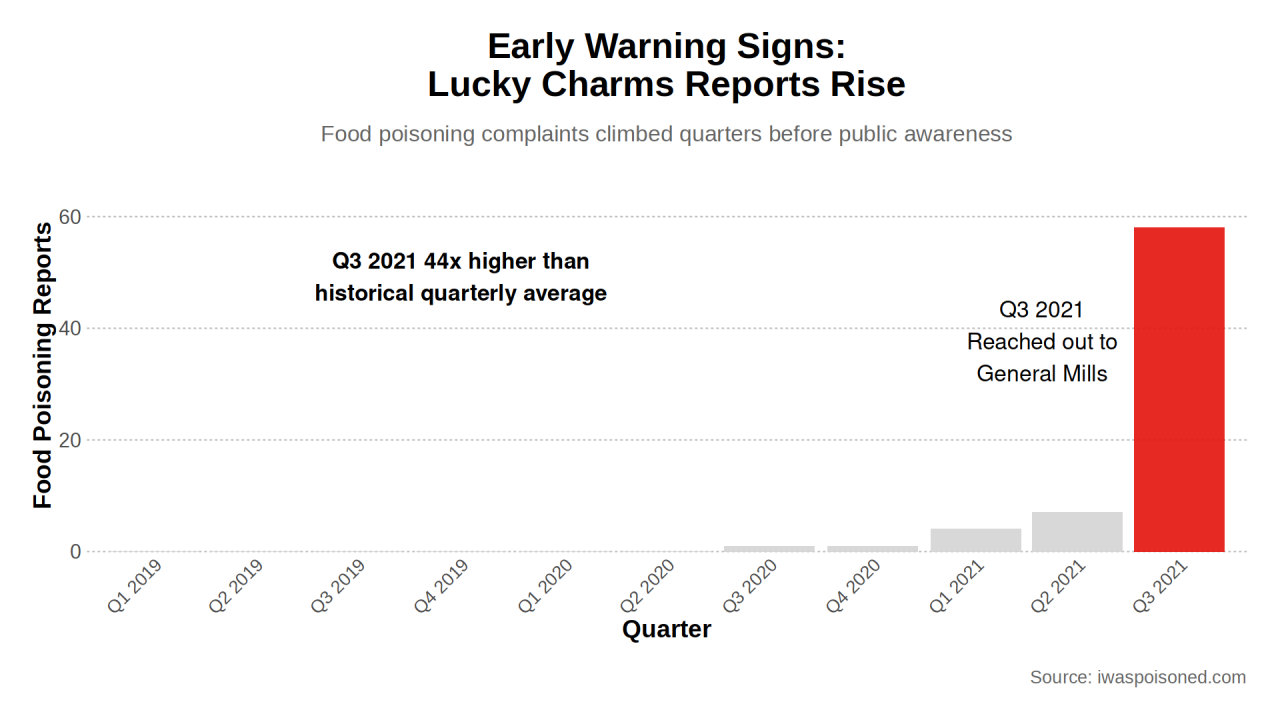

It’s rare to discover a genuinely new innovation in food safety, so last week I was delighted to read a case study by IWasPoisoned.com that showcased a new tool for food safety managers.

The case study showed how consumer reports of food poisoning linked to the consumption of Lucky Charms breakfast cereal in 2021 provided insights into the presence of a mystery contaminant.

I was impressed by the statistical rigour that IWasPoisoned used to interpret a sudden jump in consumer complaints linked to the breakfast cereal. The data was compared to baseline data - astonishingly, the usual monthly count of Lucky Charm-related illness reports is not zero - and to media amplification effects seen for concurrent outbreaks. Analyses showed that the probability of the increase being the result of random chance was less than 0.1%.

I found this so fascinating that I invited the CEO of IWasPoisoned to come talk to us at a webinar next month.

I’m keen to hear more about the insights they gained with the Lucky Charms mystery illnesses and discover how they could pinpoint specific manufacturing sites while the manufacturer, General Mills, could not.

And I’m interested to learn how today’s huge data sets, combined with new smart tools to interpret, analyse and verify, allow us to use consumer data confidently and systematically in our quest to keep food safer.

Systems like IWasPoisoned give brands the ability to tap into the ‘hive mind’ of consumers. I can’t wait to find out more about how tools like this can help food companies reduce the size of outbreaks and recalls while protecting consumers and their brands.

Save the date:

Webinar with Patrick Quade from IWasPoisoned.com

Thursday, September 11, 4 pm CT USA (Friday morning for Australia, New Zealand). More details next week.

Revisit the Lucky Charms mystery outbreak here:

🍏 Lucky Charms: How Could They Make People Sick? | Issue 43 🍏

🍏 Are Lucky Charms Causing a Massive Foodborne Illness Outbreak in the USA? | Issue 42 🍏

Read the IWasPoisoned case study on LinkedIn here:

The Lucky Charms Investigation: A Case Study in Data Surveillance

The Rotten Apple in print

If you love to read offline or want to catch up on past issues, you’ll love our downloadable e-books.

We’ve just published the latest compilation, which covers Issues 176 to 200 and includes gems like This is Food Fraud, Food Defence Case Study: Cyber-sabotage! and the ultra-popular food safety photo competition of Issue 191.

Grab your copy today. Bonus: they’re searchable and link-click-able.

Past Issues E-books

Twice a year we publish a compilation of past issues as an e-book in pdf format, for paying subscribers.

A Rare Food Fraud-Related Recall

A faked inspection mark prompts a recall in the US

While food fraud can result in food safety problems, it’s very rare to see a recall for food fraud that is initiated prior to any reports of consumer illness. So I was very interested to see a recall in the USA last week associated with food fraud.

The agency that initiated the recall, the Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), says they are concerned that the recalled products pose a risk to consumers. It has designated the recall a Class I, which is the most serious classification for recalls by that agency, reserved for hazards with a reasonable probability of causing serious adverse health consequences or death.

Five days ago, a manufacturer in the US announced it would recall 32,000 pounds (14.5 metric tonnes) of sausage, pork chops and ribs after it was caught faking the USDA mark of inspection that must be carried on all meat products manufactured in the United States.

The product bore a false establishment number, which made it seem like it had been produced under the supervision of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) inspectors.

The recalled products bore false marks of inspection and carried the establishment number EST. 1785. There is no such establishment registered with the USDA.

What makes this unusual among food fraud incidents is the recall has been initiated even though there have been no reports of consumer illness or injury from these products.

The recall was initiated because the FSIS considers food produced without inspection to be dangerous, saying it “may contain undeclared allergens, harmful bacteria, or other contaminants that put consumer health and safety at risk”.

Sadly, last year we saw evidence that FSIS inspection is perhaps less effective than the agency seems to imagine when meat products produced WITH inspection caused the deaths of 10 people from Listeria.

The ready-to-eat liverwurst linked that Listeria outbreak was made at a USDA-registered establishment by Boar’s Head. Before the outbreak, the facility had been described as filthy and contaminated, with condensation dripping onto food, mold, insects, food residues and “general filth” by inspectors representing the FSIS – the very people supposedly positioned in the facility to prevent contamination and protect consumers.

So call me a cynic, but a relatively small selection of not-ready-to-eat food produced without FSIS inspection seems no more risky than a truckload of ready-to-eat liverwurst produced with FSIS inspection.

However, I digress. The interesting thing to note with this recall is that the root cause is fraud. The legal framework in this case is the Food, Drugs and Cosmetics Act (FD&C Act (1938)), which considers food marketed with false information to be “misbranded”, making it illegal in the United States.

Beyond the FD&C Act, and using my definition of food fraud, which is “deception, using food for economic gain1” this incident is an example of food fraud: the company sold their products with a fake trust symbol – the USDA establishment number – and in the process acted deceiptfully to achieve economic gain, in this case by gaining market access that would not have been possible without the false USDA mark.

From a lawyerly perspective, proving ‘fraud’ in a court of law usually requires proof of intent. That is, the prosecutor has to show that the deceptive behaviour was done on purpose and was not a simple mistake.

We don’t have the same burden of proof when we discuss food fraud as non-lawyers. However, I do consider intention when deciding what to include in my weekly food fraud reports for The Rotten Apple.

I use my expertise to make a judgment about whether a deception could be intentional. If I judge an incident is more likely than not to be the result of an intentional act by someone in the supply chain, then I consider it ‘food fraud’.

Using fish species substitution as an example, the mislabelling of cheap fish like tilapia as expensive fish like Red Snapper is likely to be intentional because it gains the perpetrator extra money. Doing it the other way around - misrepresenting expensive fish as cheap fish - doesn’t result in a gain and is more likely to be accidental than intentional.

In the case of the fake USDA establishment number, I judge the deception to be intentional, with the understanding that this could be difficult to prove in a fraud case in a court of law.

But it is good to know that someone was paying attention and checking the authenticity of the establishment mark on these products and that the agency was willing to take action against the business. If only they had been so proactive at Boar’s Head last year.

In short: A recall has occurred after authorities learned of the fraudulent use of an establishment number on meat products in the USA 🍏 The recall was initiated to protect consumer safety, although no one was sickened 🍏 This is a rare example of a potential food safety problem from food fraud being identified by a government agency proactively, before anyone was harmed 🍏

Source:

Food Safety News and Resources

Our food safety news and resources roundups are expertly curated and never boring.

This week’s roundup includes unusual outbreaks, a deadly multi-country Listeria outbreak, a mass poisoning event from an oil mix-up and pistachio dramas...

Click the preview box below to access it.

Radioactive Shrimp: The story behind the recall notices

No doubt you’ve heard that breaded shrimp was withdrawn from sale in the United States last week after some samples were found to contain the radioactive chemical Caesium-137 (Cs-137).

What’s the real story? How did this happen, and is there other radioactive food out there that hasn’t been discovered yet?

What is Cesium-137?

Caesium-137 (Cs-137) is a radioactive version (‘isotope’) of the chemical caesium. Normal caesium (Cs-133), a silvery-white metal, has fewer neutrons than Cs-137. Cs-133 is stable, not radioactive and naturally occurring.

Cs-137, with four more neutrons than ordinary caesium, is unstable and radioactive, with a half-life of about 30 years. It doesn’t occur in nature and is the result of nuclear fission, which occurs in nuclear reactors and during nuclear weapons detonations.

Cs-137 is a common byproduct of nuclear reactors, nuclear weapons testing, and nuclear accidents. It is not naturally found in the environment but can be present as radioactive fallout from these human-made nuclear events.

In the environment, Cs-137 behaves like soluble salts, moving easily through air and water, allowing it to get into soil and plants. It emits beta particles and gamma radiation, which pose health risks, including an increased risk of cancer.

Cs-137 does not cause objects in its vicinity to become radioactive.

What is a radionuclide?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uses the term radionuclide in its recall notices. A radionuclide is an atom with an unstable nucleus that undergoes radioactive decay, emitting radiation in the process.

Cs-137 is one type of radionuclide. The terms ‘radionuclide’ and ‘radioactive isotope’ are interchangeable in this context, both used to describe unstable isotopes that emit radiation.

What was wrong with the shrimp?

One shipment of frozen breaded shrimp from Indonesia was discovered by the FDA to contain Cs-137 when they tested “multiple samples” for radionuclides.

The amount detected was low: 68 becquerels per kilogram (Bq/kg), which is 17 times lower than the FDA’s Intervention Level for Cs-137 and a level that the FDA says would not cause acute health effects.

The FDA performed the radionuclide tests after U.S. Customs & Border Protection (CBP) reported the detection of Cs-137 in shipping containers at four U.S. ports: Los Angeles, Houston, Savannah, and Miami. Presumably, the shrimp and other samples they tested had been transported in these shipping containers.

The shrimp that tested positive for Cs-137 was stopped at the border and never made it into U.S. commerce, but the FDA recommended that shrimp from other shipments from the same manufacturer be recalled anyway. As a result, a number of brands are being recalled from retail outlets, including Walmart.

The FDA’s investigation is ongoing; however, the agency says the shrimp “appears to have been prepared, packed, or held under insanitary conditions whereby it may have become contaminated with Cs-137 and may pose a safety concern.”

Since shipping containers and shrimp both contained Cs-137, some kind of cross-contamination must have occurred. Because four containers were affected but only one shipment of shrimp, the shrimp could not have contaminated the shipping containers. Rather, Cs-137 from one of the containers somehow got into the shrimp.

How exactly could any chemical, let alone a radioactive one, get into shrimp from a shipping container? Lots of ways, I guess, but none of them good. Or legal.

The regulatory situation

Imported foods are covered under the Foreign Supplier Verification Program (FSVP) Rules of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), with the exception of seafood. Seafood importers do not have to comply with FSVP, but they do have to ensure the food they import is safe.

The Sanitary Transport Rule of FSMA covers food only when within the U.S.A.

The FDA states in its advisory notice that the product violates the Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act because it appears to have been prepared, packed, or held under insanitary conditions.

An import alert has been created by the FDA to stop products from the manufacturer from entering the country until the issue is resolved.

Could this be a terrorist act?

Putting radioactive materials into food seems exactly the horrible type of food terrorism we might expect from people trying to create terror and panic.

However, the levels detected by the FDA were quite low - not high enough to cause serious illness until years into the future, if at all. Terrorists aim for high-impact results and sub-acute doses of Cs-137 in a single shipment of seafood just doesn’t seem dramatic enough to fit the bill.

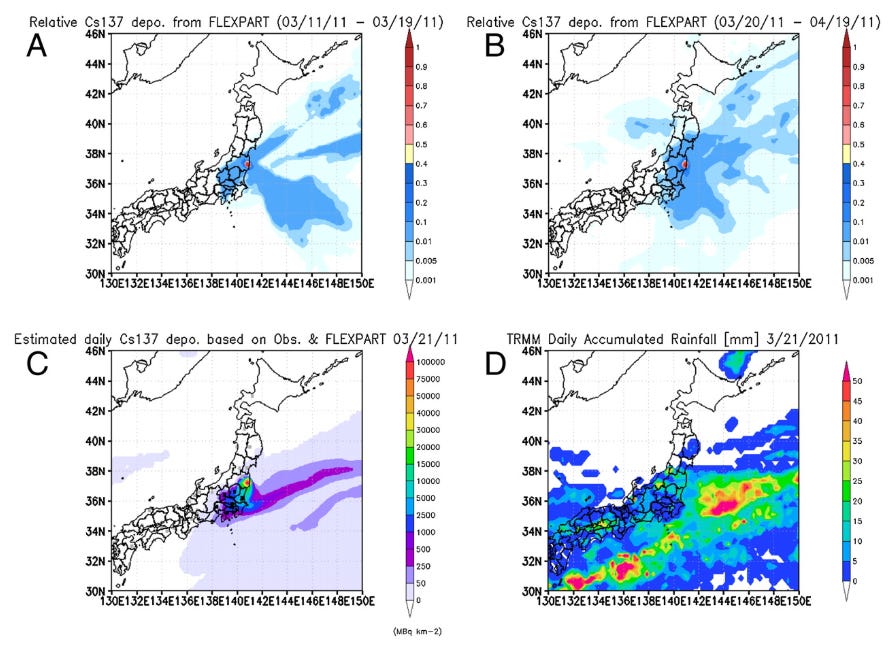

What about Fukushima?

The Fukushima nuclear accident, which occurred in Japan in 2011 after a nuclear power plant was damaged by an earthquake and tsunami, resulted in emissions of Cs-137. The radioisotope was deposited on land and in the ocean.

Seafood from the surrounding areas and further afield continues to show signs of Cs-137 from the accident, although the risk is generally considered to have been mitigated appropriately through harvesting restrictions.

So it is possible for Indonesian shrimp to contain Cs-137 from ocean contamination from the Fukushima disaster; however, that does not explain the Cs-137 in the shipping containers.

Perhaps the containers were in a region of Japan that experienced significant fallout, and have recently returned to circulation for the first time since the disaster.

Could other foods be affected?

I don’t know if this is just the tip of the iceberg. I hope not. But we only discovered this problem with breaded shrimp because border authorities noticed shipping containers were contaminated. To my knowledge, Cs-137 testing is not performed routinely on most foods.

The FDA must suspect problems with other lots of shrimp from the same Indonesian supplier; otherwise, they would not have suggested recalls of product that had not tested positive for Cs-137.

Hopefully, more foods containing high levels of man-made radioisotopes like Cs-137 are not discovered in the U.S. supply chain. At this time, we don’t know - but I bet food testing agencies have begun to check.

In short: Customs agents detected radioactive caesium in shipping containers at four U.S. ports and alerted the FDA 🍏 The FDA tested “multiple samples”, presumably of foods that had been transported to the US in those containers 🍏 One shipment of frozen breaded shrimp from Indonesia was found to contain caesium-137 at levels 17 times lower than the FDA intervention level 🍏 That shipment did not enter the U.S. marketplace 🍏 The FDA encouraged businesses that had received other shipments of shrimp from the same manufacturer to recall their products 🍏 The non-acute nature of the contamination and (apparently) small quantity of food affected does not match the profile of food terrorism 🍏

Main source (others are hyperlinked in the text):

U.S. FDA Human Foods Program (2025). FDA Advises Public Not to Eat, Sell, or Serve Certain Imported Frozen. [online] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/alerts-advisories-safety-information/fda-advises-public-not-eat-sell-or-serve-certain-imported-frozen-shrimp-indonesian-firm.

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

Undercover honey investigators

In Issue 81, I wrote about how my daughter, who loves honey and eats a lot of it here in Australia, complained that all the honey she tasted while travelling in Europe had no flavour, telling me it tasted like sugar water.

A German news outlet has published a documentary about their investigations into honey fraud in Europe and it certainly aligns with my daughter’s “sugar water” opinion.

While the video begins with all the information we have come to expect from honey fraud stories, such as the differences between various test methods and regulatory standards, things soon get more interesting.

Journalists set up their own fake honey business, visit honey traders and processors with hidden cameras, and even send people to China to collect evidence of fraudulent practices.

“The syrup really passes the NMR test?” asks an undercover investigator of a Chinese syrup supplier. The answer is simple: “Yes”.

The journalists even make their own fake honey using special syrups designed to trick the nuclear magnetic resonance test (NMR) widely used in Europe for honey authentication. And they succeed: a blend of authentic honey and 20% special syrup was identified in the NMR test as authentic. Blends made with ordinary syrups were flagged as inauthentic.

“The math is simple”, an anonymous German honey trader tells them, “If I add 20% syrup to my honey, my margin would almost double. You have no chance against such competitors.”

For English subtitles, click CC on the YouTube display to activate captions, then in Settings choose ‘Subtitles’, then ‘Auto-translate’, then ‘English.

Thank you, Sander for telling us about this fascinating investigation and documentary.

Methanol in paprika - the inside story

Huge thanks to Clare Menezes of CMM Advisory Ltd, who wrote to share her expertise and shed light on the unusual adulteration I mentioned in my summary of June’s EU Monthly Agrifood Fraud Suspicion Report.

Clare explained that methanol in paprika