207 | The flesh-eating bacterium that causes deadly foodborne illnesses |

Plus: a new food defence threat, and a food fraud supplement for paying subscribers

This is The Rotten Apple, an inside view on food fraud and food safety for professionals, policy-makers and purveyors. Subscribe for insights, latest news and emerging trends straight to your inbox each Monday.

Food fraud mitigations: a guide (+ templates and examples)

The flesh-eating bacterium that causes deadly foodborne illnesses

A new food defence threat: smart glasses

Quality versus production (just for fun)

Food fraud news, incidents and horizon scanning

Hi,

Welcome to Issue 207 of The Rotten Apple. It’s great to have you here.

Huge apologies to all my Swiss readers and to chocolate lovers everywhere: last week I had a brain fart and said Lindt was a German company 😮 (unforgivable!). Lindt is Swiss. Sorry.

In this week’s issue, you’ll find a link to our latest guidance: food fraud mitigations. It includes a video, a downloadable template and examples.

Also this week, a new food defence risk and another uncommon food pathogen: Vibrio vulnificus. A gazillion years ago (it seems), the marine bacterium was the subject of my university honours thesis. It was a muddy job collecting samples from estuarine sediments in oyster-growing regions, and a tedious job filling hundreds of MPN tubes with bright green selective media.

But the aspect I remember most strongly: the smell of the autoclaved blender receptacles containing smooshed up oyster flesh and innoculum... like an overcooked oyster milkshake 🤢.

As always, there’s food fraud news at the end of the issue, with an interesting genuine article test to spot counterfeit confectionery. Plus, don’t miss the major warning for organic sugar and organic foods containing sugar.

Have a great week,

Karen

Cover image: Fabrikasimf on Freepik

Food fraud mitigations: a guide

I talk a lot about food fraud in this newsletter: awareness is the first step in protecting your business from purchasing fraud-affected ingredients, products and materials. But awareness is only the beginning.

This month’s special supplement for paying subscribers provides a guide to mitigation actions and control plans for food businesses, and includes a template for a food fraud mitigation plans to make your next audit a breeze.

Click the preview box to access the guide and template.

From aphrodisiac to nightmare: the flesh-eating bacterium that turns oysters deadly

What you need to know about the deadly foodborne pathogen Vibrio vulnificus

Vibrio vulnificus is a Gram-negative, motile, curved rod-shaped bacterium naturally found in warm marine and estuarine environments, particularly in brackish coastal waters. It belongs to the genus Vibrio and is related to Vibrio cholerae, the bacteria responsible for cholera.

V. vulnificus naturally occurs in marine environments and is concentrated in filter-feeding shellfish such as oysters, clams, and mussels, where it multiplies within their tissues, causing no apparent harm to the molluscs.

In humans, it can cause severe infections through the ingestion of raw seafood or exposure of wounds to seawater. It possesses virulence factors like a polysaccharide capsule, several extracellular toxins that allow it to invade tissues, and the ability to evade the immune system, which contribute to its high morbidity and mortality rates.

Although rare relative to other foodborne pathogens, it accounts for 95% of seafood-related deaths in the United States, due to its high virulence and rapid disease progression.

A growing risk

V. vulnificus infections in the United States have increased substantially over the past decades, with cases increasing eightfold from 1988 to 2018 along the Eastern U.S. seaboard and Gulf Coast.

In 2025, there have been at least 57 confirmed cases across 11 U.S. states, higher than in past years. For example, in the state of Louisiana, the number of cases (17 cases, 4 deaths) is significantly higher than the average of 7 cases and 1 death during the same period over the prior 10 years, according to the Louisiana Department of Health.

There have also been significant increases in cases of V. vulnificus in Australia, with researchers noting an increase in wound infections from the bacterium in areas previously not susceptible during times of high rainfall and flooding.

Foods, symptoms and incubation periods

Foodborne infections of V. vulnificus are usually associated with the consumption of raw or undercooked seafood, particularly oysters harvested from warm waters.

The consumers most at risk are people with compromised immune systems, particularly those with chronic liver disease, cancer, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, thalassemia, or those taking immunosuppressive medications. Additional risk factors include recent stomach surgery or medications that reduce stomach acid. Men are reported to have higher susceptibility compared to women.

Individuals with high serum iron levels are at heightened risk, a phenomenon explained by the influence of iron availability on bacterial growth and virulence.

Symptoms typically develop quickly, often within 24 hours of exposure. For foodborne infections, early gastrointestinal symptoms include vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal cramps.

From the gastrointestinal tract, V. vulnificus can enter the bloodstream, causing a severe infection known as septicaemia or sepsis, which results in fever, low blood pressure (septic shock), and painful blistering skin lesions.

Wound infections caused by V. vulnificus may cause necrotising fasciitis – a ‘flesh-eating infection’ which destroys tissue and may necessitate amputation.

Mortality rates are high; about 20% of infected individuals die, sometimes within 48 hours of symptom onset, particularly if they have predisposing medical conditions.

Control methods

Control methods for Vibrio in seafood are difficult. Oyster depuration - holding live oysters in clean water to allow them to purge contaminants - works well on bacteria that are found in oysters' gastrointestinal tracts, such as environmental contaminants like faecal coliforms. However, it does not work well on bacteria that exist naturally in the marine ecosystem, like Vibrio.

Since the bacterium is more prevalent when waters are warmer, harvesting areas are monitored. Some oyster-growing regions enforce harvesting restrictions during periods when water temperatures are too high.

For example, the State of Florida has a Vibrio Control Management Plan, which requires aquaculturists to adhere to time-temperature guidelines, including time of harvest and speed of putting the shellfish into the cooler after harvest.

The plan also includes oyster tagging, which allows the shellfish to be traced to the lease and parcel to establish a chain of custody and allow for traceback if an illness occurs.

Seafood sellers should purchase shellfish only from reputable sources and check that they are properly labelled with licensing or registration information as required in the area.

They should also educate consumers on safe consumption practices, strongly advising against eating raw or undercooked oysters, especially for individuals with chronic illnesses or weakened immune systems.

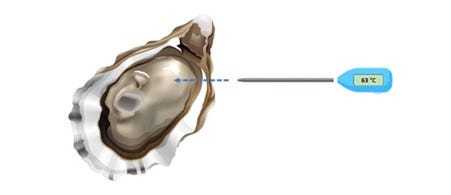

Cooking oysters to an internal temperature of at least 63°C (145°F) is recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), while the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommends they be cooked to an internal temperature of 90°C (194°F) for 90 seconds.

Takeaways for food professionals and consumers

V. vulnificus is a deadly foodborne pathogen that causes system-wide sepsis when it passes from the intestinal tract of susceptible individuals who have consumed raw or undercooked seafood, particularly shellfish.

It is naturally present in temperate and warm shellfish growing environments and is not associated with environmental pollution. As such, it is difficult to remove by traditional oyster depuration methods.

Control methods include limiting harvest areas and times to avoid the warm water conditions favoured by the pathogen, prompt refrigeration after harvesting, purchasing seafood only from reputable sources, educating consumers about the risks of consuming raw seafood and cooking to the correct internal temperature.

In short: 🍏 Vibrio vulnificus is a marine bacterium that causes wound infections and foodborne illnesses 🍏 It has a mortality rate of 20% 🍏 The prevalence of infection is increasing due to warming waters from climate change 🍏 Control methods include harvesting shellfish only when water temperatures are low and cooking 🍏

Main sources:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2024, About Vibrio Infection, CDC. Available online:, https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/about/index.html.

Archer, EJ, Baker-Austin, C, Osborn, TJ et al. 2023, 'Climate warming and increasing Vibrio vulnificus infections in North America', Scientific Reports, vol. 13, p. 3893. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-28247-2.

Jones, MK & Oliver, JD 2009, 'Vibrio vulnificus: Disease and Pathogenesis', Microbiology Spectrum, PMC2681776. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2681776/.

Louisiana Department of Health 2025, Vibrio vulnificus: Information and Prevention, Louisiana Department of Health. Available online: https://ldh.la.gov/news/vibrio-vulnificus-2025.

Hughes, MJ et al. 2024, 'Notes from the Field: Severe Vibrio vulnificus Infections in Eastern US States Following Heat Waves', MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 115–117. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7304a3.htm.

Links to minor sources are hyperlinked within the text.

A new food defence threat: Smart glasses

The other day, I heard from a fellow food safety professional about the risks posed by new models of smart glasses, which are almost indistinguishable from ordinary reading glasses or sunglasses.

She purchased Ray-Ban Meta glasses and described how easy it would be to use them to record the inside of food factories.

This is a food defence risk. The glasses could be used to record critical areas inside a facility, including processes, staff movements, and computer screens (think formulas, access systems), with the recording used to plan an attack.

Smart glasses pose threats to the security of your site and should be included in your food defence threat assessment, or TACCP plan.

Controls for the threats posed by smart glasses are mostly centred on staff training and awareness. You want your employees to know what to look out for with smart glasses, why it’s important to prevent the unauthorised use of smart glasses inside the facility and what to do if they suspect someone is using smart glasses.

Additionally, ensure that all induction policies for employees, contractors and visitors explicitly prohibit the use of smart glasses and other covert recording devices.

Remember, even if the wearer does not intend harm from the use of smart glasses, their use could inadvertently result in the leaking of confidential information since the glasses are connected to the internet. For example, search engines, AI tools and social media accounts have access to the images collected by smart glasses.

Good to know: although smart glasses are supposed to display a light when taking a picture or recording, this can be covered easily, and nefarious users have published instructions online showing how to disable the light.

Learn more about Meta Ray-Bans: what they look like, how easily they can be used discreetly, and how difficult it is to detect them in ordinary interactions in this video by The Verge (“Some super spy shit right there…”). Worth a watch.

Quality versus production (just for fun)

It’s an oldie but a goodie… though many modern businesses have got a more collaborative and supportive relationship between the quality and production departments than as depicted here.

Below for paying subscribers: Food fraud news, horizon scanning and incident reports

📌 Food Fraud News 📌

In this week’s food fraud news:

📌 A brand owner shares their counterfeiter’s tricks

📌 Warnings for organic sugar

📌 Illegal meat imports out of control in the UK

📌 Seafood fraud, vinegar fraud, crab poaching, horrible sausages and more.

Genuine article test: fake chocolate brand

A brand owner whose Dubai-style chocolates were faked by fraudsters has published pictures of real and counterfeit packages for consumers, so they can distinguish between real and counterfeit versions of their popular confectionery.

The counterfeit version failed to carry the correct allergen warnings about the presence of nuts.

The counterfeits were one of three brands of Dubai-style chocolate that were recalled in the United Kingdom in August due to the presence of undeclared peanuts, almonds, cashews, and walnuts.